More than 80 percent of agricultural expansion in the tropics between 1980 and 2000 came at the expense of forests, reports research published last week in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

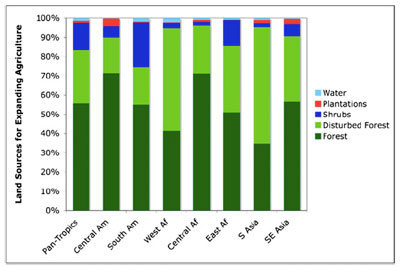

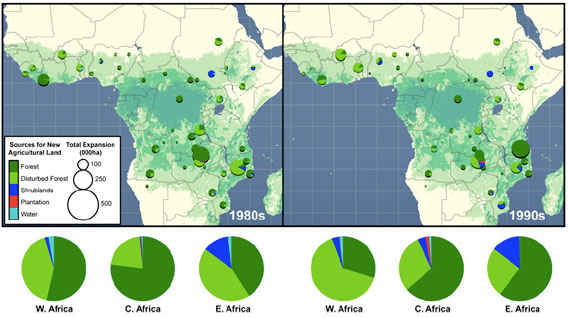

The study, based on analysis satellite images collected by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and led by Holly Gibbs of Stanford University, found that 55 percent of new agricultural land came at the expense of intact forests, while 28 percent came from disturbed forests. The remainder came from shrub lands.

“This finding confirms that agricultural expansion did not arise largely from previously cleared land and that agricultural expansion indeed has been a major driver of deforestation and the associated carbon emissions,” write the authors. “This study confirms that rainforests were the primary source for new agricultural land throughout the tropics during the 1980s and 1990s.”

The origins of new agricultural land, 1980–2000. Bars show the average proportion of land sources comprising new agricultural land in major tropical regions. Caption and image courtesy of Gibbs et al 2010. |

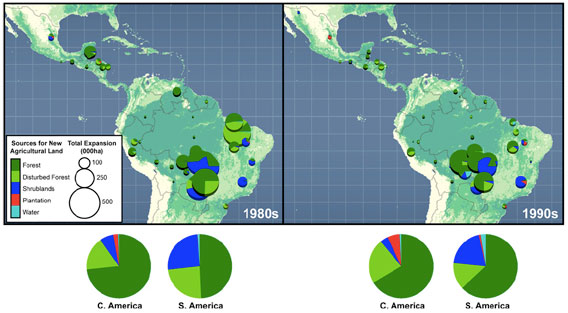

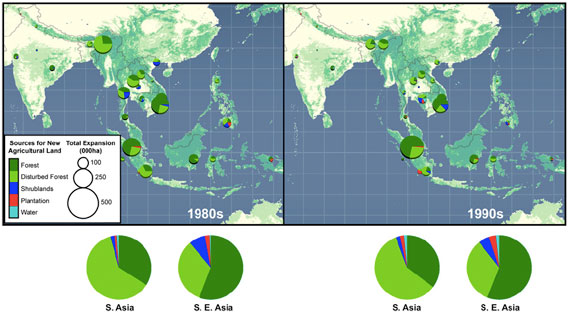

Total agricultural land increased by 629 million hectares (ha) in developing countries the 1980s and 1990s, including a net rise of than 100 million ha in tropical regions. Much of the expansion occurred in Brazil, Indonesia, and Malaysia, countries that now produce 40 percent of the world’s of sugarcane, soybeans, and palm oil, but have experienced high rates of forest loss. Conversion of these forests generated substantial greenhouse gas emissions.

“This has huge implications for global warming, if we continue to expand our farmland into tropical forests at that rate,” said Gibbs in a statement. “Every million acres of forest that is cut releases the same amount of carbon into the atmosphere as 40 million cars do in a year.”

Gibbs and colleagues found “cropland expansion was faster in the 1980s than in the 1990s” but “pasture showed the opposite trend” with the largest increases occurring in South America. The area of agricultural land converted from intact rainforests in Latin America was 13 percent higher in the 1990s than the 1980s.

“We are seeing mounting tension between growing the food, feed and fuel and keeping forests standing,” Gibbs told mongabay.com.

Sources for newly expanded agricultural land in tropical America during the 1980s and 1990s.  Sources for newly expanded agricultural land in tropical America during the 1980s and 1990s.  Sources for newly expanded agricultural land in tropical America during the 1980s and 1990s. The pie charts show the relative proportions of land sources across broad regions and for individual Landsat sites, which are scaled according to the size of the agricultural land expansion. Captions and images courtesy of Gibbs et al 2010. |

The scientists found little evidence that agricultural lands converted from forest areas were being abandoned long enough to enable forest regeneration during the study period.

“We estimate that less than 5% of previously agricultural land later supported natural vegetation during the 1980s and 1990s,” the authors write.

The paper also cautions that the trend of agricultural expansion at the expense of forests is likely to continue.

“If the agricultural expansion trends documented here for 1980–2000 persist, we can expect major clearing of intact and disturbed forest to continue and increase across the tropics to help meet swelling demands for food, fodder, and fuel,” the authors write. “Indeed, recent studies confirm that large-scale agro-industrial expansion is the dominant driver of deforestation in this decade, showing that forests fall as commodity markets boom.”

Nevertheless the authors are guardedly optimistic about the future for tropical forests. They highlight the emergence of reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD), an approach that could see tropical countries compensated for protecting forests. Under some proposals, farmers and ranchers might receive carbon payments to incentive expansion on grasslands and degraded agricultural lands instead of on forest lands. Further the consolidation of the drivers of deforestation from hundreds of millions of rural poor to a limited number of corporations is presenting new opportunities for activists to confront forest destroyers.

Click to enlarge |

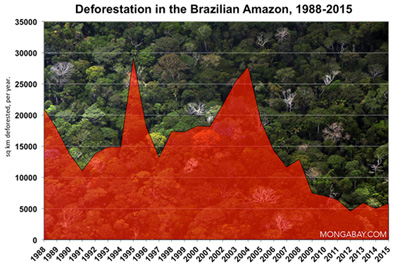

“The good news is that we are seeing the tides change in Brazil where roughly one fourth of tropical agricultural expansion occurs,” said Gibbs via email. “It’s encouraging to see that deforestation rates have been declining since 2004 while production of soy, sugarcane and cattle are increasing.”

“Brazil has stepped up enforcement of environmental laws and also reduced credit access to known deforesters. However, the soy moratorium led by Greenpeace and others have also substantially contributed by using consumer-driven market pressure to forge partnerships with industry and ensure that soy farms and more recently, cattle operations, are not leading to new deforestation.”

“It is important to remember though, that we are in global economic slump. The real question is whether the Brazilian government and moratoriums will be strong enough safeguards when prices soar again.”

“Continued pressure from activist groups combined with international climate agreements could provide a real opportunity to shift the tide in favor of forest conservation rather than farmland expansion.”

|

Regional findings

Asia:

Americas:

|

CITATION: H. K. Gibbs, A. S. Ruesch, F. Achard, M. K. Clayton, P. Holmgren, N. Ramankutty, and J. A. Foley. Tropical forests were the primary sources of new

agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. PNAS www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0910275107

Related articles

How Greenpeace changes big business

(07/22/2010) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation. A prime example of this power is evident in a string of successful Greenpeace campaigns, which have targeted some of the largest drivers of deforestation, including the palm oil industry in Indonesia and Malaysia and the soy and cattle industries in the Brazilian Amazon. The campaigns have shared a common approach: target large, conspicuous consumer-facing companies that sell in western markets.

In Battle to Save Forests, Activists Target Corporations

(06/24/2010) The image of rainforests being torn down by giant bulldozers, felled by chainsaw-wielding loggers, and torched by large-scale developers has never been more fitting: Corporations have today replaced small-scale farmers as the prime drivers of deforestation, a shift that has critical implications for conservation. Yet while industrial actors exploit resources more efficiently and cause widespread environmental damage, they also are more sensitive to pressure from consumers and green groups. As a result, activists have more power today than ever to affect corporate behavior and slow the dizzying pace of tropical deforestation worldwide. That power has been on display in recent months, as campaigns by environmental groups have forced major corporations to stop doing business with companies accused of widespread deforestation.

Changing drivers of deforestation provides new opportunities for conservation

(12/09/2009) Tropical deforestation claimed roughly 13 million hectares of forest per year during the first half of this decade, about the same rate of loss as the 1990s. But while the overall numbers have remained relatively constant, they mask a transition of great significance: a shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation and geographic consolidation of where deforestation occurs. These changes have important implications for efforts to protect the world’s remaining tropical forests in that environmental lobby groups now have identifiable targets that may be more responsive to pressure on environmental concerns than tens of millions of impoverished rural farmers. In other words, activists have more leverage than ever to impact corporate behavior as it relates to deforestation.