Oil development could destroy the most biodiverse part of the Amazon

Oil development may destroy richest part of the Amazon rainforest

mongabay.com

August 12, 2008

|

|

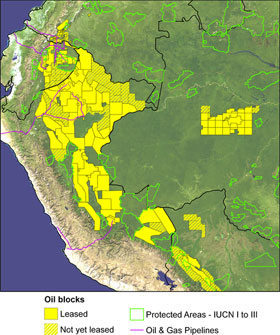

688,000 square kilometers (170 million acres) of the western Amazon is under concession for oil and gas development, according to a new study published in the August 13 edition of the open-access journal PLoS ONE. The results suggest the region, which is considered by scientists to be the most biodiverse on the planet and is home to some of the world’s last uncontacted indigenous groups, is at great risk of environmental degradation.

Tracking some 180 oil and gas projects operated across Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and western Brazil, researchers from Save America’s Forests, Land Is Life, and Duke University generated a comprehensive map of hydrocarbon concessions in the region. The assessment reveals that oil and gas blocks are concentrated in the most intact part of the Amazon rainforest, including national parks — both Yasuní National Park in Ecuador and Madidi National Park in Bolivia are under concession.

“We found that the oil and gas blocks overlap perfectly with the most biodiverse part of the Amazon for birds, mammals, and amphibians,” said study co-author Dr. Clinton Jenkins of Duke University. “The threat to amphibians is of particular concern because they are already the most threatened group of vertebrates worldwide.”

Photos of an uncontacted tribe in the Terra Indigena Kampa e Isolados do Envira, Acre state, Brazil, near the border with Peru, caused a stir when they were released by Survival International, an NGO, in May 2008. The indigenous group is said to be threatened by oil exploration in the area. © Gleison Miranda/FUNAI. |

“The most dynamic situation is unfolding in the Peruvian Amazon,” said lead author Dr. Matt Finer of Save America’s Forests.

The study shows that 64 oil and gas blocks cover 490,000 square kilometers — about 72 percent — of the Peruvian Amazon, an area significantly larger than California. 56 of blocks have been concessioned since 2003 and some overlap lands titled to isolated indigenous groups.

“The way that oil development is being pursued in the Western Amazon is a gross violation of the rights of the indigenous peoples of the region” said Brian Keane of Land is Life, “International agreements and Inter-American human rights law recognize that indigenous peoples have rights to their lands, and explicitly prohibit the granting of concessions to exploit natural resources in their territories without their free, prior and informed consent.”

Uncontacted groups are particularly at risk of diseases from the outside world. Recent first contacts in the Amazon have typically resulted in mortality rates exceeding 50 percent.

Oil and gas blocks in the western Amazon. Solid yellow indicates blocks already leased out to companies. Hashed yellow indicates proposed blocks or blocks still in the negotiation phase. Protected areas shown are those considered strictly protected by the IUCN (categories I to III). Image courtesy of PLoS ONE |

Beyond threats to human populations, oil and gas extraction can result in direct deforestation as well as contamination of waterways and lands with oil and drilling byproducts. For example in the Ecuadorian Oriente, environmentalists estimate that Texaco spilled more than 17 million gallons (64 million liters) of crude oil and dumped some 20 million gallons (75 million l) of other toxic chemicals into rivers during its 28 years of operation.

Oil and gas development is often accompanied by road-building which provides access to previously remote areas and facilitates deforestation, colonization, and illegal logging, mining, and hunting.

“Filling up with a tank of gas could soon have devastating consequences to rainforests, their peoples, and their species,” said co-author Dr. Stuart Pimm of Duke University.

Reducing the impact of oil and gas development in the Amazon

While the authors express concern over the outlook for the region, they suggest a series of measures to reduce the environmental impact of oil and gas development, starting with limiting road construction.

“Oil access roads are a main catalyst of deforestation and associated impacts,” write the authors. “Roadless extraction would greatly reduce

environmental and social impacts.”

The authors note that some firms are experimenting with roadless blocks, including Petrobras in Ecuador, which is instead using helicopters to transport personnel, materials, and equipment.

At least 35 multinational oil and gas companies operate the 180 blocks that cover 266,000 square miles of the Western Amazon in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and western Brazil. |

Finer and colleagues also recommend strengthening of environmental impact assessments for oil and gas projects, arguing that the current processes are “inadequate due to a lack of independence in the review process and a lack of comprehensive analyses of the long-term, cumulative, and synergistic impacts of multiple oil and gas projects across the wider region.” They suggest region-wide assessments to better gauge the impact of oil and gas development as well as agreements to uphold the rights of indigenous groups living in concessioned zones.

The authors end with a broader look at the underlying driver of oil and gas development in the region: rising global energy demand. Efforts to reduce this demand could include the use of alternate energy sources and binding limits on greenhouse gas emissions. Ecuador has already offered to leave blocks in Yasuní National Park unexploited in exchange for financial compensation. The area would be aside the for wildlife and indigenous people.

“While the history of oil and gas extraction in the western Amazon is one of massive ecological and social disruption, the future need not repeat the past,” the authors conclude.

Matt Finer, Clinton N. Jenkins, Stuart L. Pimm, Brian Keane, Carl Ross (2008). Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002932