- A field biologist sheds light on the use of scent dogs to study and conserve species, from armadillos to whales.

- While breed doesn’t seem to matter, a key requirement for a conservation dog is its ability to want to work for reward, especially a chance to play.

- Maintaining a conservation dog includes housing, feeding, care, and training handlers, but dogs’ success in detecting wildlife samples and the DNA, diet, and hormone information these provide can make them cost-effective.

Every field ecologist has a short-list of moments that they’ll never forget: be it a first glimpse at an elusive study species, a dangerous encounter, or witnessing a weird and wonderful wildlife spectacle.

For me, a lifetime highlight will remain the day when a giant armadillo ambled out of its Brazilian savanna burrow and nearly walked right over my shoes (these remarkable creatures have extremely poor eyesight). Since the purpose of this particular expedition was to locate wildlife feces (scat), I was all the more pleased when my field partner and conservation dog, Mason, moved past the armadillo to sit at a scat and await his prize: several minutes of tennis ball play reward.

As a ball-obsessed black labrador trained to locate scat of giant armadillo, giant anteater, jaguar, puma, and maned wolves, Mason had no interest in the study species itself. His reward, and indeed mine, came in locating the samples left behind by these species. From the samples, I would later extract DNA and hormones, as well as information on parasites and diet. So, while I wanted nothing more than to follow the rarely seen giant armadillo down its trail, I knew I owed it to Mason to reward him for his prize. I set down my camera, took out Mason’s saliva-soaked tennis ball, and gave it a toss.

I’d arrived in Brazil with a team of three dogs and their handlers and a goal of studying rare and endangered wildlife in the Brazilian savanna. I had many preoccupying questions. Would the dogs chase or otherwise harass wildlife? How would the dogs react to poisonous snakes or the hundreds of ticks that seemed to pile on them with each visit to the savanna? Would their work be affected by the intense heat? Would the training we had done on samples from captive animals transfer to their ability to locate scat from these species in the wild?

The dogs, from Packleader Dog Training and the University of Washington’s Conservation Canine Program, were trained to locate scat of maned wolf, jaguar, giant anteater, and puma back in the States. But we hadn’t had access to giant armadillo scats, so we had to rely on training Mason using just a very few samples we could obtain after arriving in Brazil. Mason’s indication on an armadillo scat that day was confirmation to me that he had been able to layer on this species with relative ease – and that despite having found hundreds of maned wolf or giant anteater samples (much more locally common species), he still had the nose for armadillo. It also showed me that Mason was the right dog for the job: willing to ignore passing wildlife and keep focused on the task at hand – using his powerful olfactory capacity to locate scats from target species.

As our results would show, not only had Mason and his canine companions adapted to the local conditions and proven their ability to detect elusive species, but they were able to find lots of samples (we collected more than 1500), had consistent detection rates, and lacked bias. Our dog teams not only found scat in all types of habitats and across seasons, but also in inundated marsh and underneath the surface soil (when scats were taken into ant tunnels).

Dog days of tropical fieldwork

The primary requirement for success in selecting a conservation dog is its ability to want to work for reward. For field dogs, play tends to be the best reward drive, since even a hot, tired dog is still inclined to play – even if just by sitting and chomping on its ball. Heat tolerance can be another key consideration and potential limitation, but we found dog teams were consistently able to sample about 4-6 hours a day if we started at sunrise.

We also learned some lessons about size and shape of dogs for particular types of fieldwork. Longer-legged dogs, for example, fared better at sampling in the tall grass and inundated marshes (not a surprise, as this build resembles that of one of our target species, the long-legged maned wolf).

Repurposed pups

The leading conservation dog programs based in North America use rescue dogs, and often mixed breeds, from shelters. Some, including Mason, are found as strays, but most are brought in when well-meaning owners have exhausted themselves failing to meet the demands of a dog with boundless energy. Conservation jobs give the dogs a new lease on life. Breed doesn’t seem to matter, although tracking dogs are typically avoided since the goal is to have the dogs pick up scent from the air and hence over long distances.

Nosing around

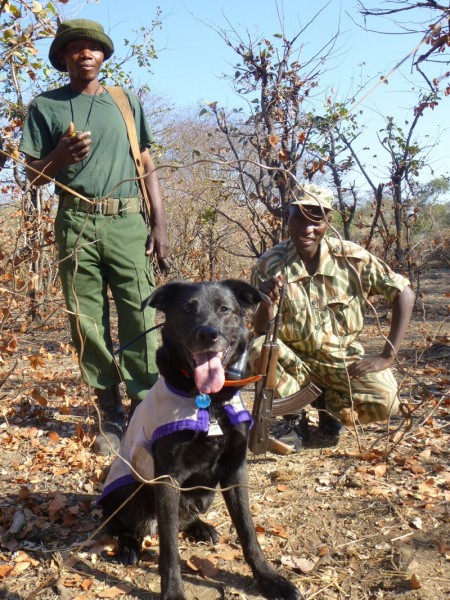

In the past decade since our studies began in Brazil, the scent dog work has not only continued in the temperate region – a recent study helped scientists assess and map key black and grizzly bear habitat in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem – but also extended to the tropics, including tigers in Asia, ocelot and jaguar in Central America, and cheetah in Africa. In Brazil, local researchers worked with law enforcement to train dogs that now help collect jaguar samples across the country.

Outside of forests and grasslands, conservation dogs have helped guide researchers to floating whale poop – allowing the samples to be located and collected before they sink. Samples are then analyzed for hormone levels to understand how boat traffic is affecting populations of right whales in the Atlantic and Orca in Puget Sound.

Today, wildlife professionals use dogs for more than helping with research. Dogs locate rare species such as desert tortoises in advance of development projects, and they help detect carcasses at wind farm sites. Anti-trafficking and poaching efforts, which have for years employed dogs at ports, are now finding success taking the dogs to the field. In Africa, for example, dogs trained to detect metal snares are proving 25 percent better at locating the deadly traps than humans alone.

Canine considerations

For wildlife professionals considering using this living technology (akin to employing a super power scent ability), key considerations include the fairly large start-up costs, as well as upkeep: dogs require housing, maintenance, specialized care (in our case, an hour of de-ticking each afternoon), training, and people that specialize in working them in the field. This is an investment that doesn’t start or stop at the life of a given field project, so leasing dogs is often a good option, and several programs offer this service.

Costs can be significant when compared to, for example, use of remote cameras to detect species. But when detection rates and the ability to gather additional information (such as DNA, diet, and hormones) are considered, employing dogs is often cost-effective.

Further, dogs score well in the 3-Rs of tech needs for the field: being Rugged, Reliable, and Repeatable. Mason once spent several months in Alberta, Canada sampling for caribou, moose, and wolves in the snow (sometimes finding samples buried under two feet of snow) before then getting refreshed at his training center in under a week and then heading off to work in the Brazilian tropics. As with cameras and other non-invasive detection technology, transferability of dogs between sites and species is really helpful. Our work showed that ‘layering on’ additional species did not affect their success. Dogs are, however, living creatures. When Mason got chased and attacked by a group of peccaries, for example, we were sidelined for three weeks while his wounds healed.

For more information on working with conservation dogs, contact:

The author, Conservation Canines, Packleader Detector Dogs, Working Dogs for Conservation.

Reference:

Vynne, C., Skalski, J.R., Machado, R.B., Groom, M.J., Jácomo, A.T.A., Marinho-Filho, J., Ramos Neto, M.B., Pomilla, C., Silveira, L., Smith, H., Wasser, S.K. 2010. Effectiveness of scat-detection dogs in determining species presence in a tropical savanna landscape. Conservation Biology DOI: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01581.x.