- In a new study, researchers tracked the movements of young green turtles and found that they navigated toward the Sargasso Sea, rather than drifting passively along the currents in the North Atlantic Ocean.

- While there have been theories and anecdotal evidence that turtle hatchlings travel to the Sargasso Sea and spend their “lost years” in the region, this is the first study that uses satellite tracking to confirm that green turtles are indeed going there.

- A previous study by the same group of researchers also tracked the movements of loggerhead turtles into the Sargasso Sea, although their journeys were found to be more nuanced.

- Experts say the study draws attention to the importance of protecting the Sargasso Sea and tackling issues such as plastic pollution.

After spending two months incubating in eggs, it’s time for green sea turtles to break out of their shells. The newly hatched reptiles scale the steep sides of their nests by clambering up the discarded eggshells of their siblings, and together they scuttle across the sand and paddle into the ocean. Then they disappear — not only from sight, but from scientific knowledge. No one has definitely known where green turtle hatchlings go and what they do for the next two or three years of their lives. But that’s changing now.

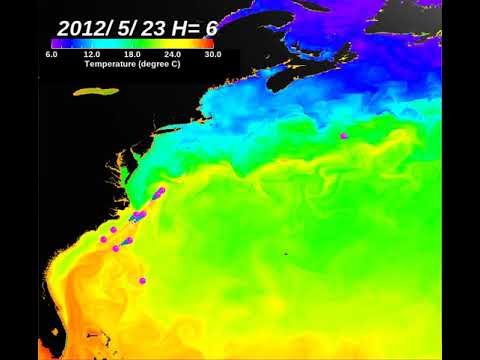

A new paper in The Proceedings of the Royal Society B has provided insight into the so-called “lost years” of endangered green turtles (Chelonia mydas) by tracking the movements of 21 juveniles released off the southeast Florida coast. Over the course of about 150 days, most of the turtles made their way to the Sargasso Sea, an area of open ocean in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre, rather than allowing the currents to push them northward toward the Azores.

“One of the long-held ideas was that these [green turtles] are passive little drifters,” lead author Katherine Mansfield, a marine turtle expert at the University of Central Florida, told Mongabay in an interview. “Historically the turtles were just assumed to swim offshore, get into these gyre currents, and then drift for several years in a big circle around the Atlantic. But what we found [was that] they had very directed movements into the gyre.”

This paper builds upon a 2014 study by Mansfield and colleagues that tracked the movements of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) across the Atlantic. Most of the loggerheads were found to also move out of the presiding currents, although their movements into the Sargasso Sea weren’t as pronounced as those of the green turtles.

“The loggerheads kind of blazed the trail, and gave us a little more insight that things may be a lot more complex than what we first realized and/or assumed,” Mansfield said. “We were excited that the green turtles went into the Sargasso Sea and it was a nice validation that, ‘OK, so maybe this really is a thing, and that the Sargasso Sea is something that we need to pay more attention to, and protect, or at least identify as an area needing protection for a variety of young species that may use it on nursery habitat.’”

The Sargasso Sea does not currently have any form of large-scale protection, yet it faces threats from numerous human activities, including commercial fishing, shipping, pollution from floating debris such as plastic, and even the possible harvesting of the Sargassum seaweed in the near future.

For the new study, the researchers collected green turtle hatchlings from wild nests in Boca Raton, Florida, and raised them for several months in a laboratory setting until they measured about 12 to 18 centimeters (5-7 inches) and weighed more than 300 grams (11 ounces), about the weight of a can of soup. At this size, the 9.5-gram (0.3-oz) satellite tags didn’t interfere with the turtles’ ability to dive, surface or swim, Mansfield said. Hatchlings, on the other hand, would probably sink under the weight of the transmitters, which is why the researchers couldn’t use wild hatchlings for the study.

They also had to refine their methods of attaching the solar-powered tracking devices to the animals. Green turtles have waxier shells than loggerheads, so they couldn’t use the same adhering technique for both species, but the researchers found a way to fix the tags to the green turtles without negatively affecting their growth or behavior. The tags are believed to naturally fall off in a few months.

According to Mansfield, the most likely way for the turtles to get into the Sargasso Sea is to latch onto some Sargassum mat, the marine algae that gives the region its name. Sargassum not only provides transport, but offers a “structured habitat with a rich food supply, predator protection, and thermal benefits promoting growth and feeding,” the authors write in the study.

Once the turtles are living among the seaweed, they probably don’t want to leave, Mansfield said.

“Would you choose as a little turtle to break away from and just to drift passively in ocean currents where you may not have that protection, or do you follow it into the Sargasso Sea?” she said. “Our thoughts are that it makes sense.”

David Godfrey, executive director of the Sea Turtle Conservancy, said this new study provides scientific evidence that backs up existing theories about where sea turtles go during their lost years.

“There’s been lots of theory and anecdotal information about turtles being spotted in floating mats of sargassum,” Godfrey, who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay in an interview. “Even going back to the founder of our organization, Archie Carr, who was working on turtles in the 1950s and ’60s and ’70s and wrote many books about the topic — he was convinced that the lost years were spent adrift in the Sargasso Sea with turtles taking up residence in Sargassum.

“People generally knew what the shape of that puzzle was [and] they knew what it looked like,” he added, “but they [the researchers] are helping place the pieces.”

He said the study also highlights the urgency of tackling the plastic pollution issue in the Sargasso Sea.

“[T]he debris and pollution and the plastic … that we allow to go into the marine environment … typically drifts [along] the same currents — the convergence zones — where Sargassum accumulates,” he said. “The fact that all that human waste ends up in those same areas, and we now know the turtles are definitely there too, it raises the stakes for our need to reduce that flow of plastic waste into the oceans.”

Justin Perrault, director of research at the Loggerhead Marinelife Center in Juno Beach, Florida, said the study provides vital information about sea turtle life history.

“These types of studies are important as they allow us to better understand habitat use and movements of different life-stages so that we know what life stages are vulnerable to what threats and where,” Perrault, who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay in an email. “It just gives us a fuller understanding of turtle migrations so that we can make more informed conservation decisions.”

Mansfield said there’s still a lot to learn about sea turtle species, and that others can build upon her research in a myriad of ways.

“We are finding that the turtles may be doing different things in different parts of the world [so] we can’t … just take what we know about North Atlantic turtles, and then cookie cutter stamp it all over the world because they may be doing something completely different,” she said. “Really it’s opened up a whole world of questions, and it’s kind of exciting because it’s rare to have a species that has been so well studied still have so many data gaps.”

Citations:

Mansfield, K. L., Wyneken, J., & Luo, J. (2021). First Atlantic satellite tracks of ‘lost years’ green turtles support the importance of the Sargasso Sea as a sea turtle nursery. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288(1950). doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.0057

Mansfield, K. L., Wyneken, J., Porter, W. P., & Luo, J. (2014). First satellite tracks of neonate sea turtles redefine the ‘lost years’ oceanic niche. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1781), 20133039. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3039

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.