- Climate-based conservation policies often focus on forests with large carbon stores – but what this means for biodiversity protection has been unclear.

- Previous research found a link between tree diversity and carbon storage on the small-scale, with tropical forests that have more tree species possessing larger stores of carbon. But this correlation had not been tested for larger areas.

- Researchers examined thousands of trees at hundreds of sites in the tropical forests of South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Their results indicate that on the one-hectare scale, tree diversity is low and carbon storage is quite high in Africa, while the opposite is the case in South America. In Southeast Asia, both carbon stocks and tree diversity appear to be high.

- The researchers say their results indicate carbon-focused conservation policies may be missing highly biodiverse ecosystems, and recommend a more fine-tuned approach for prioritizing areas for conservation.

As the earth gets warmer, nations are putting their hope in tropical rainforests. Located along the equatorial belt of the planet, scientists estimate tropical forests are home to around half of the world’s terrestrial plant and animal species and may store more than 250 billion tons of carbon. Because of their carbon-storage superpower, the protection of tropical rainforests has become a central facet of international climate change mitigation policies, such as REDD+. Standing for “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation,” the United Nation’s REDD+ policy framework aims to encourage developing countries to keep their rainforests in the ground – and, thus, the carbon they contain out of the atmosphere – by providing financial incentives from richer countries.

But do carbon-focused conservation approaches also protect forests that are biologically important?

Previous research indicates tree diversity may have a positive correlation with carbon storage ability – at least on the small scale. In other words, forests with more tree species may store more carbon than forests with fewer tree species.

But the tree diversity-carbon storage relationship has been little explored for larger areas. A group of international scientists sought to change this, and assessed the relationship between carbon storage and tree diversity in tropical forests at the one-hectare scale in the forests of Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America. In total, the team examined around 200,000 trees from 360 sites. They recently published the results of their pan-tropical study in Nature’s open-access journal Scientific Reports.

To their surprise, the researchers found no set carbon storage-tree diversity relationship at this larger scale. On the contrary, their results for tropical forests in Africa indicate overall tree diversity is low while carbon storage is quite high. In South America, the opposite was found, with high tree diversity but low carbon. While in Southeast Asia, both carbon stocks and tree diversity appear to be high.

The researchers say their results indicate some current conservation strategies may be aimed at the wrong places.

“If carbon storage and biodiversity are unrelated (as we found), then carbon conservation strategies will miss some high diversity forest,” said Martin J. Sullivan, a senior researcher at the University of Leeds in the UK and lead author of the study. “Protecting some areas of forest can divert threats onto unprotected forest (a process known as leakage), so it is important that these high diversity forests are not left unprotected and vulnerable.”

In their study, the researchers write their results highlight a need to assess conservation value more comprehensively, and that there are ways to do this. But it won’t necessarily be easy.

“Methods to select protected areas that consider multiple metrics of conservation value (e.g. aboveground biomass carbon and aspects of biodiversity) are available,” the authors write. “Our results support the use of such an approach over carbon-dominated prioritization incentivized under REDD+.

“Applying this in practice is challenging as it requires knowledge of spatial variation in tree diversity, composition and carbon stocks, highlighting the importance of careful identifications to species level during forest inventories. As tropical forests can have any combination of tree diversity and carbon both will require explicit consideration when optimising policies to manage tropical carbon and biodiversity.”

Since the study showed Southeast Asia’s rainforests are both carbon-dense as well as highly biodiverse, Sullivan highlighted the importance of forest conservation in this region. He said Southeast Asia is special in this way because its forests are dominated by the trees of the Dipterocarpaceae family, which comprises a group of very tall, fast-growing trees. Although this family is also found in Africa, it underwent a huge radiation in Asia.

“There are a few hypotheses for why dipterocarps get so big and grow so fast; they may need to grow tall as they have wind dispersed seeds, there may be no penalty for growing tall as risks of strong winds are less in Borneo than elsewhere, they may be able to extract nutrients more efficiently than other trees due to associations with ectomycorrhizal fungi [that live on the roots of some plants], or they may allocate more of the carbon they get from photosynthesis to growth rather than other functions compared to other trees,” Sullivan told Mongabay.

Based on this research, Sullivan and his forest scientist colleagues suggest that Southeast Asian forests should be put at the forefront of global climate change mitigation and conservation targets.

“Despite the general lack of association between diversity and carbon, our analysis demonstrates that forests in Asia are not only amongst the most diverse in the tropics but also amongst the most carbon-dense,” their study states. “Thus at a global scale a clear synergy emerges, with forests in Asia being both highly speciose and extremely carbon-dense.”

The researchers write that this conservation need is magnified by threats Southeast Asian forests are experiencing in the face of human development pressure.

“Asian forests are under substantial threat, particularly from conversion to oil palm plantations and more intensive logging than elsewhere in the tropics,” the authors write. “As a triple hotspot for biodiversity, carbon and threat, there is a compelling global case for prioritizing their conservation.”

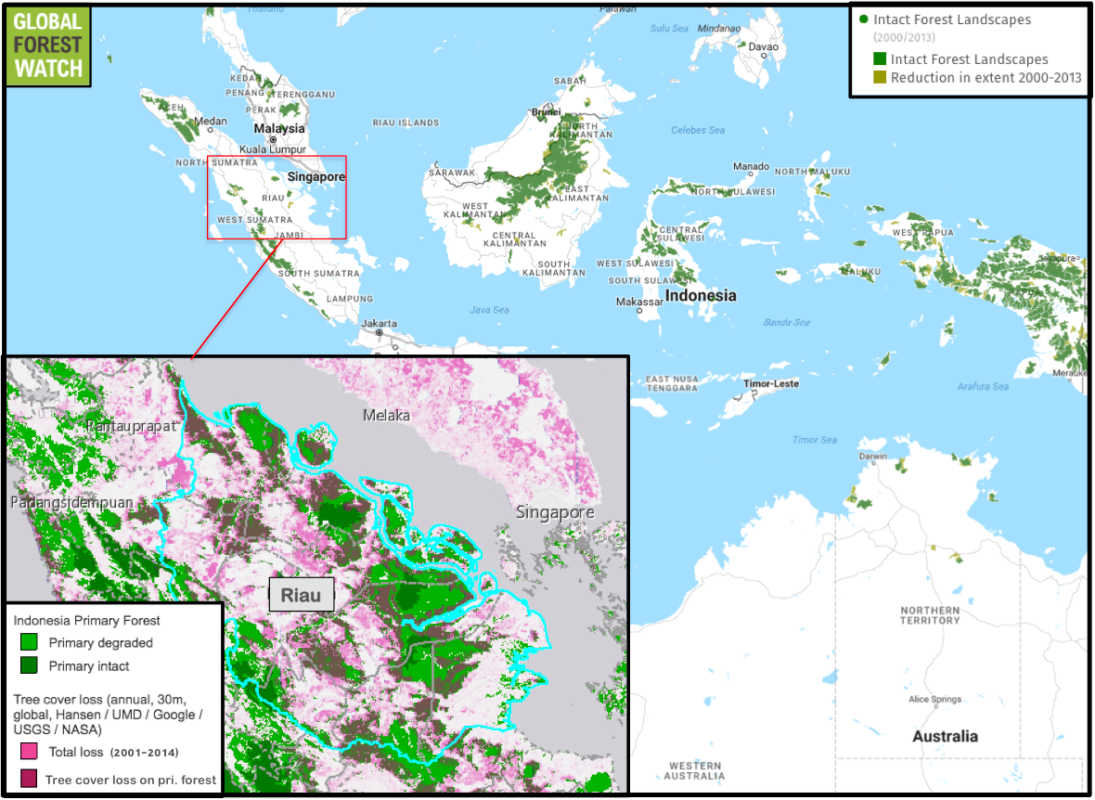

The researchers’ concerns are supported by data that show massive tree cover loss across the region. According to a multi-institutional analysis, relatively few intact forest landscapes (IFL) – areas of native land cover large and undisturbed enough to retain their original levels of biodiversity – remain on the Southeast Asian mainland. Cambodia has just one lone IFL, 38 percent of which was degraded between 2001 and 2013.

Indonesia, which has one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation, still has some IFL coverage, but only on 17 percent of its land area. Many of the archipelago’s islands are completely or nearly devoid of IFL cover. The major driver of land cover change in Indonesia has been the establishment of tree plantations for the production of palm oil, wood pulp, and other commodities.

The province of Riau on the island of Sumatra is one region that has been highly affected by this kind of industrial agriculture. The forest monitoring platform Global Forest Watch shows tree plantations covering most of its land area, with its few remaining IFLs showing degradation between 2001 and 2013.

In 2011, Indonesia enacted a moratorium on new clearing in primary forest and peatlands. While data analyzed via Global Forest Watch Commodities show a small slow-down in the clearing of primary forest in Riau since the moratorium, the province still lost 494,000 hectares of primary forest in the three years betwen 2012 and 2014 – compared to around 558,000 hectares of primary forest loss from 2009 through 2011. Elsewhere, illegal deforestation has also been reported.

Hariadi Kartodihardjo, professor of forest policy at Bogor Agricultural University (IPB), Indonesia, says the problem with Indonesia’s forest conservation lies with the government agencies that manage the forests.

“Our people don’t see the rainforests as their assets,” Kartodihardjo told Mongabay. “In Riau, the [amount of land set aside for conservation] has been shrunk from 80,000 hectares to 20,000 hectares. This kind of loss should be considered as our country’s loss. We should map the rainforests and [evaluate] the natural resource inside them … [that way, it would be] easier for us to feel the loss.”

Kartodihardjo also says that, to strengthen Indonesia’s forest conservation efforts, policymakers should focus more on the local level rather than on international policy such as REDD+.

“Indigenous communities, NGOs, and Conservation Forest Management Units (Kesatuan Pengelollan Hutan Konservasi/KPHK), are at the frontline of Indonesia’s rainforest conservation,” he said. “But unfortunately, policies regarding these three agents are not prioritized by our government.”

Citations:

Banner image: red howler monkey in Peru. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. “Intact Forest Landscapes. 2000/2013” Accessed through Global Forest Watch on April 12, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from:http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on April 12, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Margono, B.A., P.V. Potapov, S. Turubanova, F. Stolle, and M.C. Hansen. “Indonesia primary forest.” Accessed through Global Forest Watch on April 12, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Sullivan, M. J., Talbot, J., Lewis, S. L., Phillips, O. L., Qie, L., Begne, S. K., … & Miles, L. (2017). Diversity and carbon storage across the tropical forest biome. Scientific Reports, 7.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.