- The team of ecologists and environmental scientists behind the research examined 176 studies, including many local studies, in order to get a larger picture of the magnitude of hunting-induced declines in tropical mammal and bird populations.

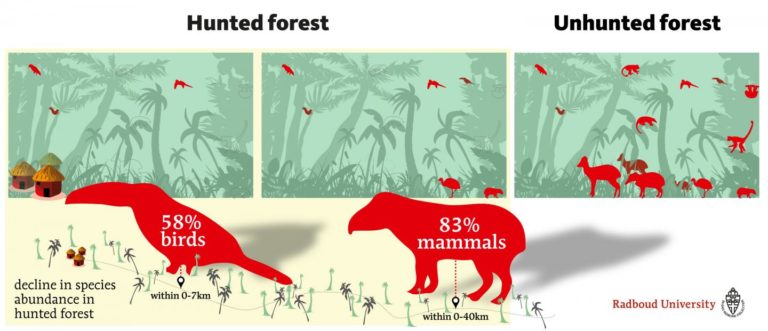

- In areas impacted by hunting, bird abundance declined by an average of 58 percent compared to areas with no hunting, while mammals declined by an average of 83 percent, according to their study.

- “Thanks to this study, we estimate that only 17 percent of the original mammal abundance and 42 percent of the birds remain in hunted areas.”

Thanks to the proliferation of cheap outboard motors and motorbikes as well as hunting technologies like modern guns, mist nets, and wire snares, which grant anyone easier access to forests and reduce the skill-level required to hunt, over-hunting is increasingly becoming one of the chief threats to wildlife, especially large mammals and other vertebrates.

Meanwhile, demand for bushmeat, wild animals for the pet trade, and medicinal products derived from animals and animal parts (like rhino horn or elephant tusk, which are highly prized by practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine) continues to grow, causing a wildlife crisis in several regions of the globe.

This is particularly true in the tropics. For instance, a 2016 study found that hunting is the biggest threat to biodiversity in Southeast Asia, not the habitat destruction that results from deforestation and forest degradation, as is commonly believed.

However, according to the authors of a paper published in the journal Science today, “a systematic large-scale estimate of hunting-induced defaunation is lacking.” So the international team of ecologists and environmental scientists behind the research examined 176 studies, including many local studies, in order to get a larger picture of the magnitude of hunting-induced declines in tropical mammal and bird populations.

“While deforestation and habitat loss can be monitored using remote sensing, hunting can only be tracked on the ground,” Ana Benítez-López, an environmental scientist at Radboud University in the Netherlands and the lead author of the study, said in a statement. “We wanted to find a systematic and consistent way to estimate the impact of hunting across the tropics.”

Benítez-López and her colleagues took the theory that hunting is more common in proximity to villages and other access points like roads as the jumping off point for their research. As you get farther from these access points, the densities of species preferred by hunters should increase accordingly, until no hunting impacts are observable. “We called this species depletion distances, which we quantified in our analysis,” Benítez-López said. “This allowed us to map hunting-induced declines across the tropics for the first time.”

The researchers determined that bird and mammal populations have taken an even bigger hit from hunting than they expected, and that that holds true across the tropics of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. In areas impacted by hunting, bird abundance declined by an average of 58 percent compared to areas with no hunting, while mammals declined by an average of 83 percent, according to the study.

“Bird and mammal populations were depleted within 7 and 40 kilometers [respectively] from hunters’ access points (roads and settlements),” the researchers write in the study. “Additionally, hunting pressure was higher in areas with better accessibility to major towns where wild meat could be traded.”

Benítez-López said that the difference in hunting’s impact on birds, which can be seen seven kilometers or 4.3 miles from access points, and mammals, whose species depletion distance extends a full 40 kilometers or nearly 25 miles from roads and villages, is chiefly due to the fact that mammals are bigger and therefore provide more meat, making them more desirable prey — even if they’ve been mostly eradicated from the vicinity of a village or road and require more travel to find. “They are worth a longer trip,” she explained. “The bigger the mammal, the farther a hunter would walk to catch it.” As demand for bushmeat in rural and urban areas has increased (recent surveys have shown that people are even bringing bushmeat from Africa to Europe in unknown, but seemingly significant, quantities), larger species have been hunted to near-extinction in the proximity of villages.

The researchers also found that commercial hunters have a larger impact on wildlife populations than subsistence hunters who are simply trying to feed their families. That’s led to mammal population densities being lower outside of protected areas than they are inside of them — which the authors specifically attribute to commercial hunting activities.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that granting a piece of land some kind of protected status automatically makes it safe for wildlife — the study determined that mammal populations have also been reduced even in protected areas.

Benítez-López and co-authors write that, “Thanks to this study, we estimate that only 17 percent of the original mammal abundance and 42 percent of the birds remain in hunted areas.”

“Strategies to sustainably manage wild meat hunting in both protected and unprotected tropical ecosystems are urgently needed to avoid further defaunation,” Benítez-López added. “This includes monitoring hunting activities by increasing anti-poaching patrols and controlling overexploitation via law enforcement.”

CITATIONS

- Benítez-López1, A., Alkemade, R., Schipper, A. M., Ingram, D. J. , Verweij, P. A., Eikelboom, J. A. J., & Huijbregts, M. A. J. (2017). The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 356 (6334), 180-183. doi:10.1126/science.aaj1891

- Harrison, R.D., Sreekar, R., Brodie, J.F., Brook, S., Luskin, M., O’Kelly, H., Rao, M., Scheffers, B., & Velho, N. (2016). Impacts of hunting on tropical forests in Southeast Asia. Conservation Biology 30 (5), 972–981. doi:10.1111/cobi.12785

Follow Mike Gaworecki on Twitter: @mikeg2001

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.