- Cameroon’s Ebo forest is home to key populations of tool-wielding Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees, along with an unspecified subspecies of gorilla, drills, Preuss’s Red Colobus, forest elephants, and a great deal more biodiversity.

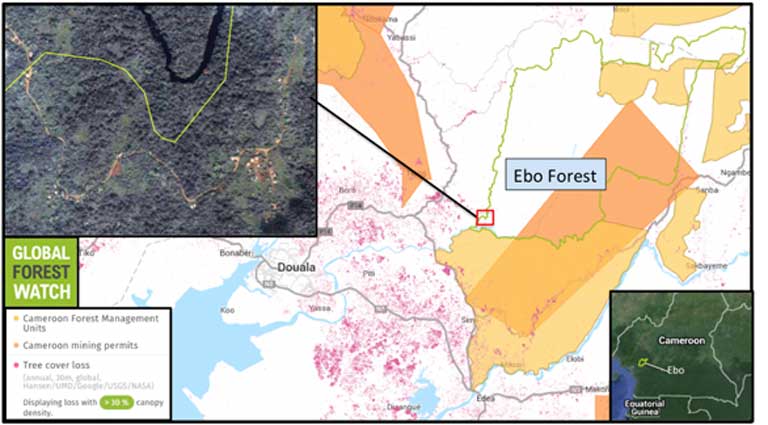

- The forest is vulnerable, unprotected due to a drawn-out fight to secure its status as a national park. Logging and hunting threaten Ebo’s biodiversity. The Cameroonian palm oil company Azur recently began planting a 123,000 hectare plantation on its boundary.

- The Ebo Forest Research Project (EFRP) has been working successfully to change the habits of local people who have long subsisted on the forest’s natural resources — turning hunters into great ape guardians. But without the establishment of the national park and full legal protection and enforcement, everyone’s efforts may be in vain.

Ekwoge Abwe’s fight drags on. As the manager of the Ebo Forest Research Centre (EFRP), he’s been part of a long running battle to set-up a national park conserving Cameroon’s Ebo forest. Seven years ago, a World Wildlife Fund Cameroon press release trumpeted the new park, saying that its designation was imminent. A high-level forest fly-over was organized to seal the deal, with the press, government officials and community leaders all joining in.

But today, Ebo remains only the Ebo forest; with no government protection, and still seen as critically important habitat renowned for its significant populations of great apes.

The Ebo forest covers more than 1,500 square kilometers (386 square miles) in Cameroon’s Littoral region, and it is very rich in biodiversity. A healthy population of Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees (Pan troglydtes ellioti), estimated to be around 700 strong, is found within its borders. And among them is the only chimp population east of Ivory Coast known to use tools for nut-cracking. The Ebo chimps use wood and stone hammers and anvils to get at the meat of the coula nut; and they use long, flexible sticks to fish for termites.

The forest also boasts Cameroon’s only Preuss’s Red Colobus (Piliocolobus preussi) population outside of Korup National Park, as well as one of Africa’s largest populations of endangered drills, (Mandrillus leucophaeus) and forest elephants.

Ebo also harbors a mystery population of gorillas, only discovered by scientists in 2002. Two subspecies of gorilla are found in Cameroon, separated by the Sanaga River; the Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) is found to the south of the river, and a small population of Cross River gorillas (Gorilla Gorilla diehli) is found to the north. Between them, 100 kilometers (62 miles) north of the Sanaga River, there is a third population, located in Ebo. These gorillas are completely cut-off from other sub-species, with no other populations found within a 200 kilometer (125 mile) radius.

“Up until now we’re still uncertain whether they are Western or Cross River gorillas, or, more interestingly, they could be a third sub-species in Cameroon,” Abwe said.

Palm oil on the border

Last Spring, Abwe spoke to Mongabay about plans being developed by the Azur palm oil company to clear forest and create a 123,000 hectare (89 square mile) plantation on the western border of the proposed national park. “They’re not out to destroy the forest,” he said then, but was surprised to be reminded of those words nearly a year later.

Azur manufactures soap and cooking oils for distribution within Cameroon. As of the end of 2016, forest had been cleared for the plantation, and a palm tree nursery was growing.

Abwe now fears that the creation of this oil palm plantation will compound the many problems facing Ebo, making the fledgling national park that much more difficult to manage once it is established. “Because [once you plant the plantation] the next thing [to come] will be a large population of poorly paid workers, who want to complement their income through hunting and farming,” Abwe said. Plantation workers will easily be able to step into the forest, hunt a few monkeys, apes or duikers, and find themselves with some extra cash.

One chief concern is that the environmental impact assessment (EIA) conducted for the new plantation was done by a firm closely connected with Azur, raising questions about the EIA’s validity. “You can’t really expect anything fair from them,” Abwe said flatly.

He also indicated that the terms of the plantation agreement are not being respected. A buffer zone several kilometres wide was originally proposed, meant to create a wide gap between plantation and forest, Abwe explained. But as things stand now, the buffer on the western national park boundary will only be a few hundred meters wide — too narrow to keep people and wildlife separate and prevent conflicts with great apes and other animals.

Source of bushmeat

Ebo already faces high hunting pressure due to its proximity to two major cities — Douala just 50 kilometers (31 miles) away from the forest, and Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital which is 150 kilometers (93 miles) distant.

Bushmeat is in high demand and commands high prices in these urban centers, so commercial hunters are increasingly attracted to nearby wild places to kill, carve up and roast animals to sell as meat.

Commercial hunters, Abwe said, focus their attention on the western and southern part of the forest, closest to the city of Douala. Hunters in the northern part of the Ebo are generally local people who spend a few days hunting in a vicinity, then sell whatever they kill to dealers, known locally as “buyum sellums.”

These commercial meat dealers travel to the local villages by taxi, motorcycle and on timber trucks and supply thriving bushmeat markets in Douala and Yaoundé. In the markets, Abwe said, you can find almost whatever kind of meat you want.

Without national park protection, Ebo’s rich biodiversity will continue ending up on Douala and Yaoundé dinner plates.

Although locals claim that hunters do not directly target Ebo’s great apes, poaching remains a problem and is one of the top two threats to the animals’ survival, alongside logging. When a hunter does not find anything else to shoot, explained Abwe, the prospect of bagging a chimp may be too enticing to ignore. And once bushmeat is prepared, most law enforcement officials wouldn’t be able to tell if the meat came from an endangered species or not.

From hunters to forest guardians

The Ebo Forest Research Project (EFRP) works with local people in the northern part of the forest to stem the flow of exploited wildlife. When the project began in 2005, its work was mainly biological. But EFRP biologists, going about their research, often came across wire snares or heard gunshots ring out through the forest. It was a problem they couldn’t ignore.

As a result, the EFRP began working directly with hunters. The researchers raised ecological awareness by educating local people to the consequences of commercial hunting, which culls vast quantities of wildlife from the forest to feed urban populations. The scientists explained that large-scale hunting leads to the “removal of a trophic level,” and that because of this “you end up having an empty forest,” Abwe said.

“We came now to a crucial part,” he added. Even though many hunters understood the importance of conserving the forest and its wildlife, and recognized that the hunting of endangered species was illegal, that awareness wasn’t enough to curtail the practice.

That’s because hunting remains an important source of income for the people living in the 19 villages surrounding the Ebo forest. A 2016 study published in International Forestry View suggests that bushmeat may be worth as much to Cameroon’s GDP as its mining sector; that’s around €97 million (US$106 million). So giving up hunting, which can be very lucrative, is often not an easy or financially feasible choice for fiscally strapped families.

That’s why it isn’t practical to criminalize hunting without providing viable alternative livelihoods. EFRP realized that finding other sources of income for villagers was absolutely essential if Ebo’s biodiversity was to survive.

So Abwe’s team went directly to the hunters to find out what they would rather do than hunt. Their responses were varied, ranging from livestock raising (pig farming), to aquaculture (fish ponds), to agriculture (growing cocoa). The EFRP team next took the hunters on a field trip to Limbe, so they could see these livelihoods in action and talk to people who were practicing them.

“Many of the [hunters] went back [to the Ebo forest villages] and started implementing these things,” Abwe said. Cocoa farms that had been abandoned were restarted, and fish ponds were created. Conflicts between hunters and law enforcement were reduced.

In 2013, Abwe was awarded the Whitley Award, also known as “The Green Oscars,” for his innovations in conserving the Ebo Forest. The funding that followed allowed EFRP to expand their Club des Amis des Gorilles (Gorilla Guardian Clubs) initiative.

The 200 members of the clubs recruited to date are former hunters from the villages encircling Ebo. Membership begins with a simple signature and a pledge to conserve the forest and the gorillas within the proposed park’s borders.

Members are charged with monitoring local gorillas, and are accompanied on their mission by a member of the EFRP team. Earlier this year Ebo’s ape population was filmed for the first time by camera traps set-up by the Club des Amis de Gorilles.

The Gorilla Guardian model has been such a success that EFRP is planning to expand the clubs to other communities, although given the limited range of gorilla populations, the focal species will change. Abwe envisages Club des Amis de Chimpanzees, or even using endangered drills as the face of conservation in the future.

Ebo Forest National Park, but when?

When asked if he knows when Ebo forest will become Ebo National Park, Abwe laughs. “I would love to have an answer to that,” he said, adding that the national park designation seems stuck in the bureaucratic pipeline

“We’ve done a lot, and the traditional [Ebo community] rulers have done a lot. We are just waiting.” Meanwhile, hunters continue killing Ebo’s animals for bushmeat, and trees continue to be felled for Azur’s palm oil plantation or by loggers.

True, Ebo’s problems are hardly new. They began in the late 1960s along with Cameroon’s bid for independence, when violent conflict spread across the country. To sooth some of that tension and improve control over the local populace, the government moved the people who lived inside the borders of the proposed national park to two villages outside.

“Much of what is today the Ebo forest was peppered by numerous small villages until the period of civil unrest,” Philip Forboseh, program manager for WWF-Cameroon’s coastal forests program, told mongabay.com.

WWF-Cameroon played a key role laying the groundwork for the park, actively supporting its creation for nearly five years, but pulling out in 2013 when progress toward the goal seemed permanently stalled. WWF judged then that it could no longer justify a costly full-blown program in Ebo without assurance of national park status, Forboseh explained.

According to Abwe, some of the community’s traditional rulers are now saying that instead of the forest being designated a national park, the people should be allowed to return to their old homes, re-establishing the former villages inside Ebo.

But other traditional rulers in surrounding villages are still in favor of the creation of the park, and in May 2014 they petitioned the government to move forward with the plan, though with no success. The opposition from the traditional rulers who wish to return to the forest has ground the process to a halt.

“We understand that the files are pending approval at the level of the Presidency, hence there is no official designation of a national park at Ebo as yet,” Forboseh said.

So the wait goes on.

Avoiding another paper park

Even if national park designation is soon forthcoming, that won’t end Ebo’s challenges. Cameroon already has several national parks, but that designation often doesn’t stop poaching and illegal logging. Bushmeat hunted in some parks is still found on sale in urban markets and wood grown on conserved lands is still shipped out to foreign markets.

While some parks are well protected, others known as paper parks are protected in name only. Many wonder if Ebo will become one of those .

Abwe is confident that the Ebo forest will not go down that route. He believes that the inclusive model that has come to dominate there — involving everyone from government officials to local traditional leaders to farmers, hunters and researchers — will save Ebo from a paper park destiny.

“Over the years we have adopted community conservation, whereby the communities get involved in managing their resources,” adding a legal arm, in the form of the national park, would formalize this relationship, he said. “We want a situation where there is ongoing biological research, ongoing community conservation in collaboration with the government to ensure the forest’s protection.”

Ebo conservation efforts are already having a significant impact, he asserted. Where before people would see a bird or monkey as little more than food for the pot, they now take pride in the biodiversity that surrounds them. They are looking, conserving, rather than just eating, he said.

But these changes in local people’s attitudes may mean little ultimately, if the forest isn’t granted protection soon.

“Until we have a national park and all these boundaries are legalized and recognized by everyone, we will continue to have this situation whereby people will be able to come and set up everything based on their economic interests,” Abwe concluded.

Whether it is palm oil companies picking away at the edges of the Ebo forest, or commercial bushmeat hunters plundering its diversity, until Ebo is offered proper protection, its ecological riches will remain at risk and up for grabs. That places one of Cameroon’s greatest natural treasures — along with its important populations of great apes — in grave danger.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.