- The new species are of the Chiasmocleis genus of humming frogs. They spend most of their life underground, coming out only a few weeks a year for “explosive breeding.”

- The frogs look similar to species already known to science, but have distinct genes and minute physical differences that researchers used to set them apart.

- They were found in the Atlantic Forest, which has been heavily degraded by agriculture. As little as 3.5 percent of the biome may remain today.

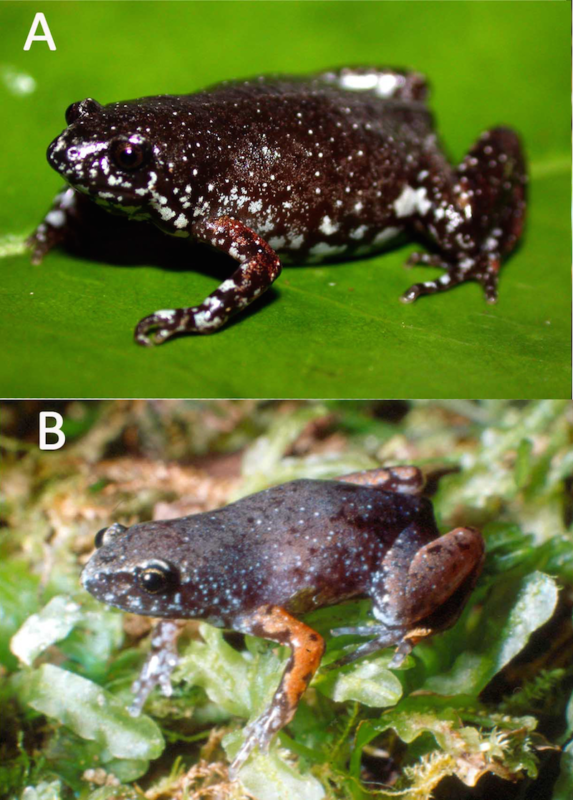

Three new “cryptic” species of frog have been discovered in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, one of the the world’s most degraded biodiversity hotspots. On looks alone, the new species are nearly identical to their brethren in the genus Chiasmocleis, so the researchers relied on DNA and skeletal analysis to make the discovery, which was published in PeerJ last month.

“Morphologically, they were very similar, so until we had additional points of data, we really didn’t know what to look for,” Rafael de Sá, a study co-author and researcher at the University of Richmond, told Mongabay.

It’s what’s on the inside that matters – at least for cryptic species, organisms that appear nearly identical yet are genetically distinct. What makes them cryptic, of course, makes them difficult to identify, obliging scientists to dig deep into their toolbox.

To discover Chiasmocleis migueli, C. veracruz, and C. altomontana – three new additions to the genus commonly known as “humming frogs” – the researchers first turned to molecular analysis. Using DNA from several specimens that were collected from the field, the researchers produced what’s called a “phylogenetic tree,” a hypothesis of genetic relationships, not so unlike a family tree. The tree revealed three genetically distinct “clusters” – each representing a new candidate species, in this case – sending the first strong signal of an impending discovery.

In search of another line of evidence, the researchers then analyzed skeletons of each specimen.

“We looked at the structures, shapes, and different characteristics of the bones” de Sá said. “And we found significant differences in the skeletal characters, too.”

Armed with a growing body of evidence, the researchers reassessed the species with a naked eye, hoping they would find at least a few visible traits. At the end of the day, you need to have some way to tell them apart, de Sá says, especially when you’re in the field and don’t have access to fancy equipment.

Sure enough, the researchers found a few – albeit small – distinguishing characteristics among specimens of each species.

“Is not that one is red and one is blue,” de Sá said. “We have smaller characteristics that are more difficult to assess, but not impossible for a professional scientist.”

According to the study, all three new species are small, brown, and “fossorial” – adapted to life underground. In fact, these frogs only surface a few weeks a year, de Sá says, for “explosive breeding.” As rude as it may be, that’s the best time to catch them because they’re calling for a mate.

“You recognize the call…and we walk until we find the point where they’re calling” de Sá said. “If it’s a good night, we may end up out until three or four in the morning.”

A good night for some, at least.

Despite the evidence the study presents, these species remain largely data deficient, the researchers say. Indeed, little is known about their geographic distribution, current threats, and population trends.

And they’re in good company. According to the The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, which catalogs animals that are at risk to extinction, almost a third of the 27 listed Chiasmocleis species are data deficient – and many more have a status that needs updating.

But de Sá is certain about one thing: “Frogs around the world are going extinct, and these frogs are not different than any other frogs.”

Indeed, nearly a third of all amphibians are listed as threatened by the IUCN, according to one study, and it’s not uncommon for newly discovered frogs to already be facing extinction.

More data is needed to determine if these frogs face the same fate, but it’s certainly not looking good. Habitat loss and degradation – the main driver of amphibian declines, according to the Living Planet Report – is rampant within the Atlantic Forest, where all three species were found. By some estimates, the Atlantic Forest retains only 3.5 percent of its primary vegetation. Agriculture is the big reason behind Atlantic Forest deforestation, with cattle ranches, soy fields, timber plantations, and other commodities supplanting native forest.

“The Atlantic Forest itself is under direct threat,” de Sá said.

And as a result, the new species might be, too.

“The survivorship of populations of C. migueli is worrisome given that forest fragments in the State of Sergipe, and surrounded areas [where it’s found], are under significant deforestation,” the researchers write in the paper.

Satellite-derived tree cover data from the University of Maryland supports their concern. Since the turn of the century, nearly 80,000 hectares of tree cover – an area equal to the size of New York City – have been stripped from the region in which C. migueli is likely to be found. Tree cover in the regions that C. veracruz and C. altomontana occupy appears fragmented, as well.

Despite the apparent threats that C. migueli and the other species are up against, there’s not enough data to list them in the IUCN Red List as “Endangered,” “Threatened,” or even “Vulnerable,” de Sá says. Now that these species are described, however, researchers will be more likely to gather data on them, which may help their case for protection.

That is, assuming they know what to look for.

Citations:

Banner image: Chiasmocleis veracruz from Forlani et al., 2017

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from:http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 30, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

Forlani, M. C., Tonini, J. F., Cruz, C. A., Zaher, H., & de Sá, R. O. (2017). Molecular and morphological data reveal three new cryptic species of Chiasmocleis (Mehely 1904)(Anura, Microhylidae) endemic to the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. PeerJ, 5, e3005.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.