- In 2015, the most recent full year for which data is available, more than 1,350 rhinos were killed for their horns in Africa and Asia.

- The vast majority of rhino horn is bound for destinations outside of the source country, meaning that conservationists in places like South Africa or India can do little to fight demand.

- Demand reduction efforts currently center on China and Vietnam, the primary destinations for poached rhino horn.

- Effective demand reduction campaigns require research into consumer behavior and careful targeting of messages.

More than 1,350 rhinoceroses were killed for their horns in 2015 alone. The majority of these killings took place in Africa, where 1,342 were killed. Asia, too, saw 24 of its greater one-horned rhinos succumb to poaching that year, all in India.

While countries like South Africa, Namibia, and to a lesser extent India are the source countries for the trade, few poached rhino horns are believed to stay within their borders. Instead, demand is driven primarily by consumers in China and Vietnam, where rhino horn is sold as a luxury good or an ingredient in traditional medicine. Between 2006 and May 2016, a minimum of 528 kilograms (1,164 pounds) of rhino horn was seized in China and at least 442 kilograms (974 pounds) in Vietnam, according to data from the NGO Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

This means that in recent years, a third of all rhino horn seizures across the globe took place in these countries – 18 percent in China and 15 percent in Vietnam.

Vietnamese and Chinese nationals were also involved in poaching cases all over the world. Data collected by EIA since 2006 indicate that 17 percent of seizures involve suspects who are identified as Vietnamese, and over a quarter of offenses involve suspects identified as Chinese nationals.

“In Africa, Chinese and Vietnamese syndicates work with locals to source rhino horn, and then rhino horn is smuggled to Asia — sometimes in containers on cargo ships with other illegal commodities such as elephant ivory,” Charlotte Davies, Crime Analyst at EIA told Mongabay in an email.

“More often, rhino horns have been detected at airports – throughout Africa, Vietnamese nationals acting as couriers have been caught with rhino horns in their luggage, sometimes in large quantities. Overall, I would say that rhino horn procurement and trafficking by criminal groups, from Africa to Asia, is systematic, well-organized and on-going.”

Smuggling through the often-porous borders in India’s Assam State, Myanmar, southern China and Vietnam is comparatively simple. According to a report by the IUCN Species Survival Commission African and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and TRAFFIC, in recent years most rhino horns from Assam moved first to Myanmar and then on to China.

This means that while rhino range states like South Africa or India can make huge efforts to stop poachers, they do not have the power to cut off demand because it comes from outside their borders. To counter this, conservationists from around the world are developing tailor-made strategies to stem East Asia’s hunger for rhino horn.

Rhino horn uses and markets

“You’ll never succeed in reducing the poaching if you can’t reduce the demand for the [wildlife] products because there’s never enough resources to protect the animals on the ground, and if you don’t reduce the demand the prices go up and up,” said Peter Knights, executive director of WildAid. “Just like the drugs trade, we believe that if there is a very strong demand you’ll never enforce your way out of this problem.”

Rhino horn is primarily made of keratin, a protein also found in human nails and hairs. It has little if any medicinal properties, but has been used for centuries in Chinese traditional medicine to treat conditions such as fever, rheumatism and even food poisoning. In Vietnam, it has recently found used as a supposed hangover cure.

“[Y]ou also have to look at the different consumers: whether they are consuming for investment, whether they are consuming to give it as a gift, if they are consuming to actually drink the rhino horn themselves — and therefore it might be different what rhino horn they prefer,” said Susie Offord, deputy director of Save the Rhino.

Noting that this is a complex issue, Natural Resources Defense Council’s Alex Kennaugh conducted a survey of wildlife consumption in five Chinese cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Kunming, and Harbin. She measured consumer behavior including preferences, willingness to pay and stigma. She found that today in China there are two distinct markets for rhino horn: medicine and luxury goods.

The use of rhino horn as a medicine in China dates back to the second century BC. Kennaugh found that although rhino horn-based medicines are not officially included in the modern Chinese pharmacopeia, nearly half of the participants in the study said they knew horn was still used in traditional medicines, mostly for fever. The study also found that the overwhelming majority of those who are aware of low-cost alternatives to rhino horn — such as Chinese herbal remedies — believe that these are more or equally effective.

As a result, the study recommends emphasizing the availability of alternative remedies for treating fever and other acute conditions. Such a campaign, the author suggests, should start with women because they represent the majority of buyers of traditional medicine.

This study also highlights that people who buy rhino horn as a luxury good do so because they want something “rare” or “unique.” In this market, Asian rhino horn is a particular object of desire. “When asked to differentiate between African and Asian rhino horn at a higher price, the most popular reasons for buying Asian rhino was that it was even rarer than African (31.6 percent) and was of better quality (26.3 percent),” says the study.

However, Kennaugh found that awareness of conservation issues and the illegal status of rhino horn dampen its demand in both the medical and luxury market. The report emphasizes that promoting wildlife conservation and substitute luxury goods could diminish “the qualities of desirableness and rarity,” and eventually counter the psychology of buying rhino horn as a luxury good.

The Chi campaign.

Save the Rhino’s Susie Offord believes informing people and raising their awareness is crucial, but only a very initial step in a behavior-change or education campaign. Demand reduction, she explained, also includes law enforcement. “What we actually need in conservation is toolkits of all these different activities,” she said.

Offord said consumption of rhino horn is being driven by a very small but very influential group of people, so raising awareness and support for wildlife conservation among the general public is important, but it isn’t enough. To really change a behavior, she said, a campaign must target a precise group, and include a positive message because positive messaging has been proven to be more effective in changing behaviors.

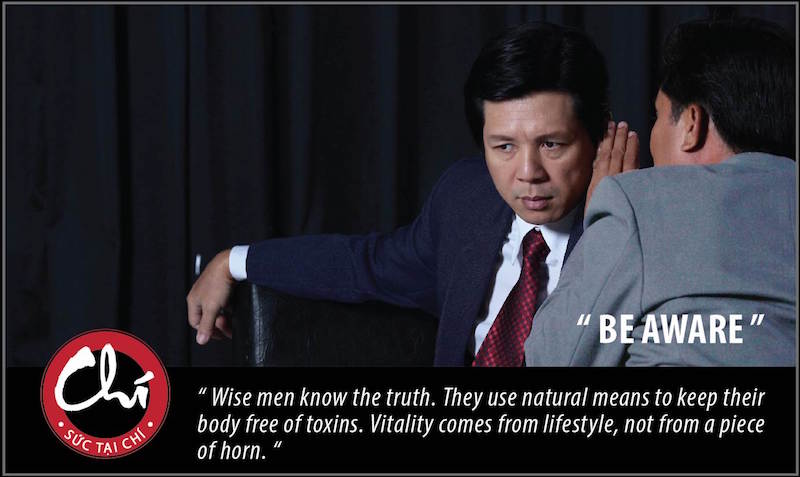

An example of this approach is the Chi campaign. Launched in September 2014 in Vietnam by TRAFFIC, Save the Rhino and other partners, it focuses on the Vietnamese concept that a person’s inner strength or “Chi” comes from within, and cannot be gained from an external source such as rhino horn.

The campaign is focused on the business community because market research of horn consumers identified the key user group as wealthy middle-aged businessmen, keen to show off their new-found wealth. This market research, explained TRAFFIC’s Richard Thomas, taught conservationists critical lessons: don’t use images of rhinos, don’t brand with a conservation organization’s logo, and don’t have spokespeople your target audience won’t listen to.

Outreach has been through “champions” – successful Vietnamese businessmen – and it’s been rolled out in collaboration with businesses and the government.

Outdoor billboards have been used in Vietnam’s biggest cities. One of them shows businesspeople together with the message “A successful businessman relies on his will and strength of mind. Success comes from opportunities you create, not from a piece of horn.” Another states that “masculinity comes from within.”

The campaign’s message has also been put in airport business lounge envelopes, in popular magazines, at golf and tennis clubs, and was included in a Corporate Social Responsibility guide for businesses dealing with wildlife consumption. This campaign also includes an online forum for discussing and learning about Chi, and networking and lifestyle events such as a Chi-themed bike ride that was joined by over 100 business leaders.

Results from the Chi Campaign have not been measured yet, but quantitative and qualitative results will be shared in the coming months and years. Still, Offord believes this campaign will be successful in promoting the idea that having rhino horn is something people should be ashamed rather than proud of.

“When the buying stops, the killing can too”

WildAid also focuses on demand reduction and public awareness in consuming countries for wildlife products. This is because it regards the consumption of wildlife products as an economic phenomenon associated with new affluence: in the case of rhino horn, poaching crises tend to coincide with rapid increases in income. For example, during the Saudi oil boom in the 1970s and ’80s, the market for rhino-horn dagger handles in Yemen went up considerably as new money flooded into that country. Similarly, rhino horn consumption in Taiwan increased in the 1970s and ’80s as its economy skyrocketed.

Rather than trying to change the mind of the consumer, WildAid focuses on changing the society in which wildlife products are consumed.

“I don’t believe you can necessarily directly influence through advertising an average-in-education 60-year-old man in Vietnam that thinks rhino horn cures cancer,” explained executive director Peter Knights. “However, you can potentially educate his children, his grandchildren, his neighbors and the people around him who could pressure him on not to consume any longer.”

Over the past years, WildAid put a lot of effort into reducing rhino horn demand in China and Vietnam. Its Nail Biter campaign, developed in partnership with the African Wildlife Foundation, focuses on the fact that rhino horn is no more effective than biting one’s own fingernails. Its ambassadors include celebrities such as Sir Richard Branson, actress Li Bingbing, actor Chen Kun, actor and singer Jing Boran and others in China, and 26 other celebrities in Vietnam.

To spread its message, WildAid uses public service announcements, billboards placed in subways, shopping centers, pedestrian walkways and outdoor screens. It also launched a social media campaign that had over 12 million views on Weibo, a Chinese hybrid between Twitter and Facebook, and over 1.5 million views on other social media platforms.

Knights credits the campaign’s high production values —their material looks like professional corporate campaigns — with garnering $286 million dollars’ worth of free media space in 2016 alone.

“It’s kind of a model that works: everybody gets something and nobody pays money, if that makes sense,” said Knights. “The stars get positive exposure as they look good in our pieces (…) and they are supporting a good cause. The television networks get quality productions of beautiful imagery featuring celebrities for free. And we get our message out.”

WildAid is also engaging Vietnam’s Buddhist community and younger generations through online comedic videos, and is producing two documentaries, one for the Chinese and one for the Vietnamese market.

“In both Vietnam and China we’ve been amazed by the list of people who have signed up to join and also the amount of coverage that the media is giving us, so there is a deep empathy here for this cause, it just needed people having a way of expressing it,” said Knights.

Communication campaigns have for decades been seen as crucial to selling products and winning elections. But Knights stresses the fact that demand reduction campaigns become mainstream among conservationists only around 2011. Behavioral change is hard to achieve, and generally involves both personal factors and broader economic and social trends, so it’s difficult to pinpoint the effect of any particular campaign. Still, conservationists are hopeful that well-designed campaigns will prove to be a valuable complement to on-the-ground efforts to save rhinos in Africa and Asia.

“Rhino horn used to be used in Japan, used to be used in Taiwan, South Korea … and through a lot of demand reduction work, it has been managed to reduce the demand,” said Susie Offord. “Now we have to make sure the same happens in Vietnam, potentially China and other countries.”

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.