- Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz touted Rachel Carson as a heroine and role model for girls in his comic strips. That may well have been the case, but the more I learned about her as I matured and my interest in nature and the environment deepened, the more she became my hero, too.

- PBS recently aired a two-hour documentary on the life, times, personal struggles, and influence of Rachel Carson, the soft-spoken, retiring, self-effacing woman who became an unlikely champion for nature and helped launch the modern environmental movement.

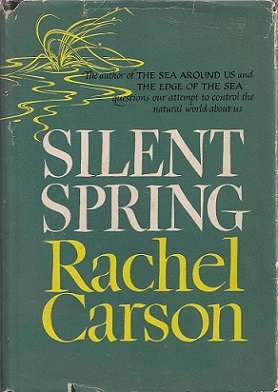

- Carson’s seminal work, Silent Spring, represented a necessary rebuke to the ascendant hubris of the “Atomic Age,” one symbolized by radioactive fallout, “duck and cover,” and the arrogant slogan “better living through chemistry.”

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily Mongabay.

I have something in common with the sassy character Lucy, Charlie Brown’s eternal “frenemy” in the iconic Peanuts cartoon series by Charles M. Schulz. We are both great admirers of Rachel Carson.

In fact, the first time I ever heard of Rachel Carson was as a kid and an avid fan of syndicated Peanuts cartoons in the funnies section of our daily newspaper and collected in cheap paperback books, which I devoured from cover to cover. (You can see Lucy mentioning Carson in this strip, and in this one as well.)

I remember to this day how on more than one occasion Lucy mentioned how much she looked up to Rachel Carson. I had no clue half a century ago just who Rachel Carson was, or even whether she was a fictitious character like Lucy or not. As a youngster, I hadn’t yet heard of Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring or realized my own life’s vocation.

Peanuts creator Schulz touted Rachel Carson as a heroine and role model for girls in his comic strips. That may well have been the case, but the more I learned about her as I matured and my interest in nature and the environment deepened, the more she became my hero, too.

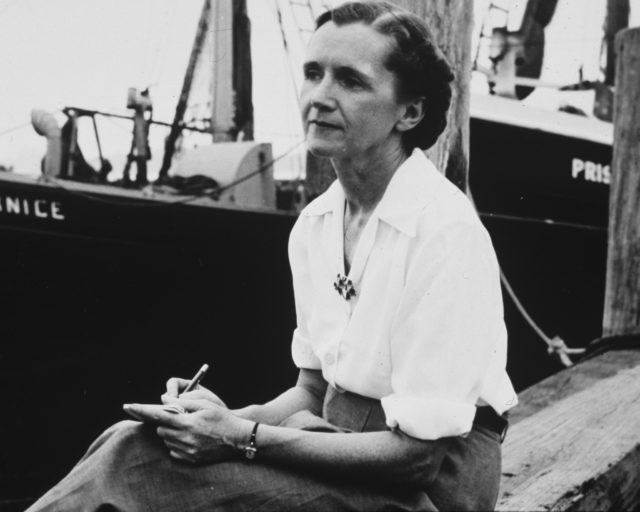

PBS recently aired a two-hour documentary on the life, times, personal struggles, and influence of Rachel Carson, the soft-spoken, retiring, self-effacing woman who became an unlikely champion for nature and helped launch the modern environmental movement. The documentary, with Hollywood star Mary-Louise Parker providing the voice of Carson, is an affectionate, intimate portrait of the very private, shy biologist and writer who grew up in Western Pennsylvania, like I did. Carson was born in 1907 on a small, hardscrabble family farm near the Allegheny River upstream of Pittsburgh. Her family struggled to make ends meet.

Encouraged by her doting mother, precocious Rachel was a serious bookworm, aspiring writer, and keen naturalist who explored every nook and cranny of her family’s 65-acre farm. By the age of eight, she had already begun writing her first stories about animals, and she became a published writer at 10. Something of a loner, she sensed her calling in life from the time she was a child, when other girls of her age would still have been playing with dolls and toys. She excelled academically, and in 1925 graduated first in her high school class of 45.

Carson attended the Pennsylvania College for Women in Pittsburgh, today called Chatham University, majoring first in English, then biology, and writing pieces for the college’s student newspaper and literary supplement. From there, after a summer course at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, she began graduate studies in zoology and genetics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Carson earned an M.S. from Hopkins in 1932 and soon landed a job in Washington as a science writer for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, which later became part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a federal agency where I myself was once an employee and for which I have served as an environmental consultant now for many years.

The death of Rachel’s father and then her sister meant that she was soon the sole provider for her aging mother and two young nieces. She began writing articles on the side for The Baltimore Sun and other publications. Ultimately, she was able to make a career of nature writing in the 1940s and ‘50s — and even gain a measure of financial security for herself and her family — with her trilogy of three evocative books about the ocean, the true love of her life: Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951) and The Edge of the Sea (1955). These books inspired readers with the same sense of passionate wonder Carson herself felt about Mother Earth. I have all three of them.

Due to the huge success of the best-selling The Sea Around Us, which won the 1952 National Book Award for Non-Fiction and remained on The New York Times Best Seller List for 86 weeks, Carson was even able to purchase a cottage on an isolated stretch of the Maine seashore. It was here, along the secluded Maine coast, surrounded and comforted by the trees, tides, and creatures that she loved, that Carson wrote her magnum opus, Silent Spring, released in 1962.

The title refers to a spring sometime in the not-so-distant future, one that comes without beloved bird songs, because the birds have all been exterminated by pesticides, or what Carson referred to as biocides, because they are toxic to all life. In Chapter One, “A Fable for Tomorrow,” she wrote:

There was a strange stillness. The birds, for example — where had they gone? Many people spoke of them, puzzled and disturbed. The feeding stations in the backyards were deserted. The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices.

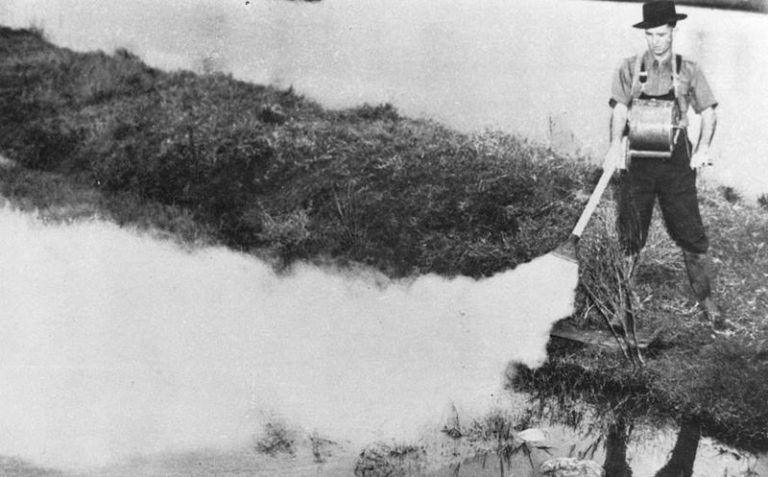

I first read Silent Spring more than 40 years ago; it was Carson’s searing indictment of the widespread, indiscriminate use of DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) and other chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides which had begun to wreak havoc on the natural world. Among their most prominent victims were the majestic birds of prey (raptors) — in particular bald eagles, ospreys, peregrine falcons, and brown pelicans — the populations of which plummeted throughout most of North America.

DDT first came into widespread use by the allies during World War II and is credited with saving the lives of many thousands of soldiers. It could be applied directly to human skin and hair with few or no immediate ill consequences (i.e., it had low acute toxicity for humans and other mammals). Such was the gratitude of the world that Swiss chemist Paul Müller was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his 1942 discovery that DDT was effective in killing insects. Unfortunately, it also proved effective in killing birds and fish, as well as persisting and accumulating in the environment. This was a serious drawback.

What DDT and its chemical relatives like aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, and heptachlor did was to interfere with the biochemical process by which calcium was deposited onto the eggshells of these birds. Because of this eggshell thinning, when adults attempted to incubate the eggs, sitting on them in nests, the weaker eggshells would crack under the weight and the developing embryos inside would die. In other words, the raptors’ ability to reproduce themselves was jeopardized. Pesticides affected them more than other birds because of the joint phenomena of “bioaccumulation” and “biomagnification,” by which toxic concentrations increased higher on the food chain.

On a personal note, in 1974 and 1975 I worked as a biological technician for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, assisting in contaminants research at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, rubbing elbows with some of the very scientists upon whose research Carson had drawn, such as Dr. Lucille Stickel, director of the Center from 1972 to 1982. The eminent Stickel was America’s first woman to become a senior scientist as a civil servant of the U.S. government, as well as to be named the director of a national research laboratory. She was also a 1974 recipient of the prestigious Aldo Leopold Memorial Award, given annually by The Wildlife Society, the professional association of wildlife managers and scientists.

More broadly, Silent Spring represented a necessary rebuke to the ascendant hubris of the “Atomic Age,” one symbolized by radioactive fallout, “duck and cover,” and the arrogant slogan “better living through chemistry.” This hubris, empowered by recent technological advances, held uncritically that man knew better than nature — could even manufacture healthier milk for babies than mothers’ breast milk — and could control and exploit nature without heed to unforeseen side-effects or long-term consequences, not only for nature but for our own species.

Not only was Silent Spring’s science mostly sound, but it spoke to the misgivings that millions of Americans were beginning to feel about the dizzying pace of change and where we as a species and our vaunted civilization were headed.

It is no exaggeration to say that Carson and Silent Spring were attacked savagely by the chemical industry and its allies and apologists, who perceived her arguments as a direct threat to their profitability and survival. Indeed, in the Cold War and sexist spirit of the times, according to one unsubstantiated account, at least one prominent critic claimed that Carson might be a Communist because she was physically attractive but unmarried for some mysterious reason.

The actual secret that Rachel Carson did keep from the public was that she was dying of cancer, a cancer that some have said she suspected might have been caused by the very environmental toxins she wrote so compellingly about in Silent Spring. That cancer finally claimed her life in April 1964, before she’d had a chance to fully defend herself and her thesis.

Yet the genie was out of the bottle. President Kennedy authorized a scientific panel to investigate her findings and accusations, which were largely vindicated. And a decade after her death, use of DDT in the United States was effectively banned; other persistent pesticides were similarly eliminated in the following years. They were replaced by less persistent chemicals that tended to have higher acute toxicity for humans and required greater care and training in their appropriate use.

Over the decades, while Carson has been revered, she has also been reviled. Some have even accused her of causing the deaths of millions of poor people from malaria and other infectious diseases in the tropics. But DDT use continued for years in some of those countries and does today. There, too, malaria continues to be a scourge, because mosquitoes inevitably evolve resistance to the insecticides intended to kill them, making higher and higher doses necessary and ultimately rendering the poisons ineffective. And it must be said that Carson never opposed pest control in principle; rather, she was an early advocate of so-called “integrated pest management,” by which a variety of adaptive methods are used to keep pests in check while minimizing collateral damage to the environment and non-target species.

The PBS documentary does a splendid job of covering all these aspects of Carson’s life, times, and legacy. I highly recommend it.

It is telling that in Rachel Carson’s instructions for her own funeral, she asked that a reading be made from the elegiac, poetic final passages of, not Silent Spring, but The Edge of the Sea. The very last paragraph of that book reads:

Contemplating the teeming life of the shore, we have an uneasy sense of the communication of some universal truth that lies just beyond our grasp. What is the message signaled by the hordes of diatoms, flashing their microscopic lights in the night? What truth is expressed by the legions of the barnacles, whitening the rocks with their habitations, each small creature within finding the necessities of its existence in the sweep of the surf? And what is the meaning of so tiny a being as the transparent wisp of protoplasm that is a sea lace, existing from some reason inscrutable to us — a reason that demands its presence by the trillion amid the rocks and weeds of the shore? The meaning haunts and ever eludes us, and in its very pursuit we approach the ultimate mystery of Life itself.

Leon Kolankiewicz is a wildlife biologist and environmental scientist and planner. He is the author of Where Salmon Come to Die: An Autumn on Alaska’s Raincoast, the essay “Overpopulation versus Biodiversity” in Environment and Society: A Reader, and was a contributing writer to Life on the Brink: Environmentalists Confront Overpopulation. He also is an Advisory Board Member and Senior Writing Fellow with Californians for Population Stabilization.