- The new frog was collected in 2001 from Ruvu South Forest Reserve in Tanzania, in habitat atypical for spiny reed frogs.

- The scientists who collected it couldn’t identify it in the field. Fourteen years later, they sequenced the frog’s DNA, which revealed that it was a species previously unknown to science.

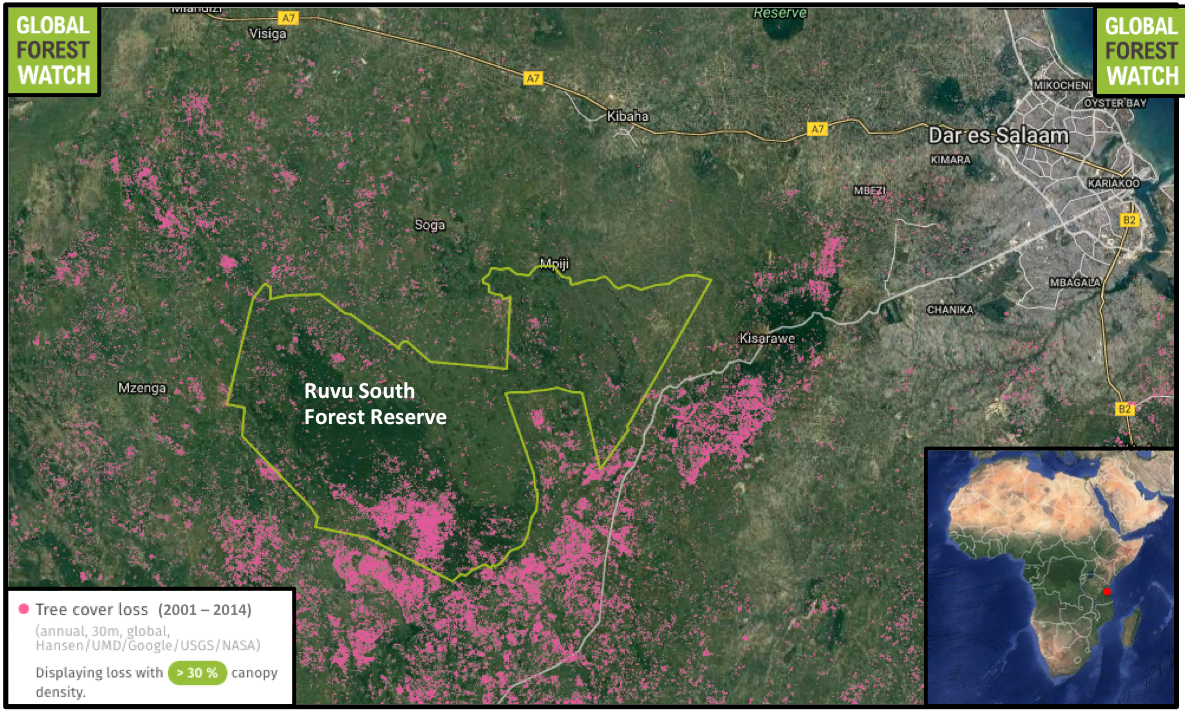

- The new species is represented by just one museum specimen. Recent attempts to find more in Ruvu South Forest Reserve failed to turn up the sought-after frogs, leaving researchers worried the species is being wiped out by dramatic deforestation affecting the reserve and surrounding areas.

You don’t have to travel far to discover a new species – just head to the natural history museum.

At least that’s how Chris Barratt, a doctoral student at the University of Basel in Switzerland, discovered Hyperolius ruvuensis, the newest species to be named in the clad of so-called spiny-throated reed frogs. The species has been preserved in the Museum of Natural History in London for more than a decade, but was never properly examined and described, Barrett says. That is, until now.

“It sat in the museum for 14 years before we took it out,” Barratt told Mongabay. “We were hoping it would still have DNA [needed for identification], and it did.”

Barratt and his colleague had a hunch that the museum specimen of now-named H. ruvuensis – then listed as another species in the spiny-throated clad – was indeed a new frog. The unusual pattern of the frog’s spines was the first clue, which prompted Barratt to analyze specimen’s DNA and morphology. Published last month in the Herpetological Journal, his analysis revealed that the specimen is in fact a new species of spiny-throated reed frog, a clade of seven species named for what he describes as a “beard” of spines, which serve a purpose still unknown.

The “new” species was collected more than 15 years ago in Ruvu South Forest Reserve, a small protected area just outside of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. At the time, David Emmett – then a wildlife biologist with the NGO The Society for Environmental Exploration – was surveying the reserve.

“One evening I could hear this reed frog calling,” he told Mongabay. “And I remember thinking: ‘Well, that’s strange. They shouldn’t be here’.”

That’s because reed frogs hadn’t been known to inhabit lowland, coastal forests – the very landscape that typified Ruvu South Forest Reserve. This piqued Emmett’s interest, so he waded into the reeds, where he found several frogs that he’d never seen before.

Like any wildlife biologist would do, he turned to field guides for answers, he said.

“Every time you find anything, you look at the books,” Emmett said. “Normally, you can identify something straight away, but when you’ve gone through to the last page of the book and the frog is still not there, you start to get excited.”

He reached the last page, but still couldn’t find a match. Sensing a possible species discovery, he collected a few of the frogs and sent them off to London, where they would later be identified.

Ruvu South Forest Reserve is an unusual place to discover a new species, the authors say. Indeed, scientists typically find new species in unexplored, intact, and isolated habitats – and none of these terms describe the reserve. According to Barratt, that’s part of what makes this discovery especially exciting.

“This discovery shows us that even a small forest reserve right next to a busy city that’s been surveyed quite a lot can yield new species,” he said. “For me, that’s really exciting.”

But it’s alarming as well, the researchers write. That’s because H. ruvuensis is likely “microendemic” to the reserve, meaning it’s found nowhere else on the planet, according to the study. In other words: if habitat in the reserve is wiped out, the species will be, too.

And habitat loss is already well underway. Tree cover data from the University of Maryland reveals that more than 3,000 hectares – or 13 percent – of the reserve’s forests were cleared between 2000 and 2014. Research by the Tanzania Forest Conservation Group (TFCG), a local NGO, points to fire and illegal charcoal production as the primary drivers.

Hyperolius ruvuensis hasn’t been seen in the wild since it was first found by Emmett’s team in 2001, despite recent attempts to track it down.

But that doesn’t mean the species is extinct, the researchers say – more research is needed to make that determination. For now, the authors recommend that H. ruvuensis be classified as Critically Endangered by The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a category saved for species that are facing a high risk of extinction in the wild, like the Sumatran orangutan.

The future of H. ruvuensis – and other species in the reserve – relies on stronger enforcement of protected area laws, Barratt says. And it’s now or never, he adds.

“There has to be something done in a way to mitigate people going into the forest and cutting a trees down,” he said. “It’s really at the stage now where it’s completely critical that they do something.”

Emmett, now a Senior Vice President at Conservation International, agrees on the state of urgency.

“To me this species being discovered and potentially disappearing is a rallying cry to the urgency of the need [for] better protected nature because we don’t know what we’ve got until it’s gone,” he said.

Citations:

Barratt, C. D., Lawson, L. P., Bittencourt-Silva, G. B., Doggart, N., Morgan-Brown, T., Nagel, P., & Loader, S. P. (2017). A new, narrowly distributed, and critically endangered species of spiny-throated reed frog (Anura: Hyperoliidae) from a highly threatened coastal forest reserve in Tanzania. Herpetological Journal, 27, 13-24.

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from:http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 02, 2017. www.globalforestwatch.org

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.