- The FAO lumps non-oil palm tree plantations into its definition of forest cover when conducting its Global Forest Resource Assessments. The assessments analyze land cover change in countries around the world using largely self-reported data.

- Nearly 200 organizations have signed an open letter authored by the NGO World Rainforest Movement to change how they define forest.

- Remote sensing technology currently doesn’t provide the ability to differentiate the canopies of forests and tree plantations. But researchers say that within a decade, technological advances will make this a reality.

- A representative of FAO said the organization is unlikely to change its definition since it is already well established and accepted by governments and other stakeholders.

What’s in a definition? For some, too much.

Nearly 200 organizations have signed an open letter to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), calling for the agency to change how they define “forest” – the very landscape honored today on International Day of Forests. FAO’s definition is too inclusive, writes the World Rainforest Movement (WRM), the non-profit that authored the letter.

“There is an urgent need for the FAO to stop misrepresenting industrial tree plantations as ‘planted forests’ or ‘forestry’… This deliberate confusion of tree plantations with forests is misleading people, because forests in general are viewed as something positive and beneficial,” WRM writes.

Tree plantations do not provide the same benefits as forests, they argue, and should be removed from the agency’s definition – the “the most widely used forest definition today,” according to a study.

The letter adds fuel to an ongoing debate about how the basic term, “forest,” is defined.

Under FAO’s definition, natural forest and tree cover are represented equally. As a result, a Christmas tree farm in Iowa is as much of a forest as a jungle in Ecuador, assuming it meets some basic area requirements. Plantations of other timber, such as rubber and eucalyptus (but not oil palm), are also considered forest by the FAO – even when the plantation is “temporarily unstocked due to clear-cutting.”

World Rainforest Movement claims that defining forest inclusive of tree plantations is problematic – as do scientists.

“You certainly should not be including plantations in a definition of forest cover,” William Laurance, a Distinguished Research Professor at James Cook University in Australia, told Mongabay. “Overall, plantations are just nothing like natural forests.”

Especially when it comes to biodiversity, he adds. Plantations typically comprise even-aged trees of a single species, forming a wood monoculture – they’re optimized for wood production, after all. Once you add in an intensive harvest cycle, there’s really not much value for wildlife compared to the native vegetation in which they evolved.

“For biodiversity and anything related to biodiversity, like pollination, plantations don’t compare to natural forests,” Laurance said. “In general, plantations would be more similar to your front lawn then they would be to a forest, in terms of their biological composition.”

Assuming your front lawn isn’t on the steps of the Amazon, that is.

Other researchers echo Laurance’s sentiment, suggesting that plantations do indeed provide value for timber production and some other services, but they should be considered separately from natural forests.

“Combining both natural forests and plantations can provide very misleading information because they offer very different things to people,” Robin Chazdon, professor emerita at the University of Connecticut and Senior Fellow at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told Mongabay. “This is not to say that plantations shouldn’t be counted – they’re important for timber production – but they should be classified as plantations.”

So why are the two unified under FAO’s definition?

The definition was developed in the late 20th century for FAO’s “Global Forest Resource Assessment” (FRA), one of the agency’s flagship projects that produces global forest cover statistics every five years. FRA relies on country-reported data to compile the assessment – a self-reporting of sorts – and the consistency and quality of those data depends on a broad, universally-accepted definition of forest.

“The aim of the definition is to enable consistent reporting and gather reliable data…,” Anssi Pekkarinen, an FAO official, said in an email to Mongabay. “Maintaining a broad definition of ‘Forest’ allows many different ‘forest types’ to be included which satisfies the needs of most countries.”

In other words, the FRA has to collate data from hundreds of countries, so simplicity is paramount.

The definition also reflects the FAO’s legacy, researchers say. Just look at the name, “Forest Resources Assessment,” said Rachael Petersen, Impacts Manager at WRI’s forest-monitoring platform Global Forest Watch.

“It’s about using forests as a resource; it’s not necessarily a conservation focused assessment,” Petersen told Mongabay. “It’s really about looking at forests as resources and, with that lens, you want to look at production forests because they’re actually providing products.”

Managed tree plantations have their place, many researchers agree. Indeed, they provide valuable economic resources and, in some cases, ecological services that are comparable to natural forests. But it shouldn’t be included in the definition of “forest,” say conservation groups like World Rainforest Movement, because this misconception produces consequences beyond confusion.

Under FAO’s definition, supplanting native forest with tree plantations does not register as deforestation – it’s reported as net neutral. This allows countries to “mask” loss of native forests when they report forest cover to the FAO, Laurance says. In India and China – this is already happening, he says. And in Chile, it’s the same story.

“If you think about that definition, a rainforest is a forest, but if it’s turned into a plantation, it’s still a forest,” Matt Hansen, a leading expert on remote sensing and professor at the University of Maryland told Mongabay.

But deforestation in the wake of plantation expansion is far from the FAO’s intent – it “must be avoided for a range of reasons,” FAO’s Pekkarinen said.

And the FAO isn’t completely to blame, according to Chazdon.

“Countries are taking advantage of the vagueness of the definition to support whatever they want to show,” she said. “That’s not really FAO’s fault.”

According to Laurance, FAO is moving towards a more objective approach to forest assessments that involves remote sensing. Just as police use security footage to verify crime reports, researchers can use high-resolution satellite imagery to verify reports of forest cover change.

But a big problem lies in their way. Although tree plantations are biologically distinct from natural forests, the two land types don’t look very different. Especially to satellites.

“With the freely available satellite imagery, often times the canopy of mature plantation forests looks very similar to natural forests,” Petersen told Mongabay. “A lot of algorithms [for analyzing satellite imagery] look at the presence or absence of tree cover, but aren’t sophisticated enough to differentiate different types of tree cover.”

As a result, harvesting trees from a plantation will register the same as deforestation, she says.

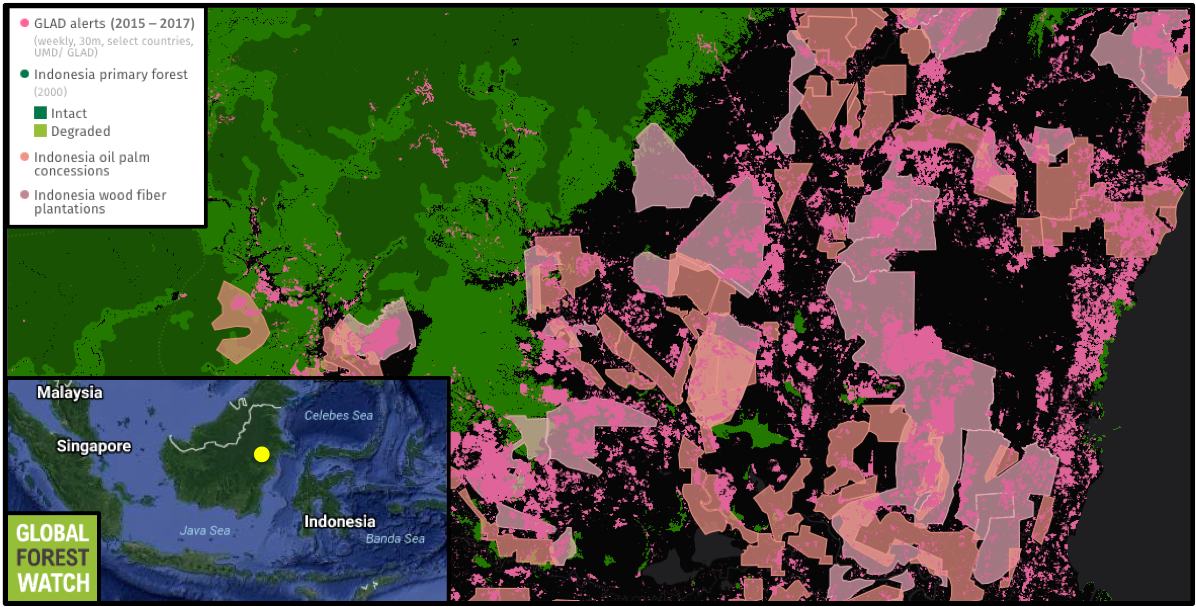

For example, take the University of Maryland’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) dataset, used frequently in reporting at Mongabay. The alerts point to areas where tree cover loss has likely occurred. Global Forest Watch, which visualizes the dataset, decisively calls these “tree cover loss alerts” instead of “deforestation alerts” because, in some cases, they may signal a plantation harvest.

So we’re back to the same problem – whether they’re pixels on a computer or numbers in the latest FAO Forest Resources Assessment, tree plantations and natural forests still have equal representation.

But not for long, researchers say.

According to Petersen, Global Forest Watch is experimenting with what she calls “deep learning techniques” – a phrase you may only hear on the streets of Silicon Valley – to differentiate natural forest from tree plantations using artificial intelligence. The technology is not unlike what Facebook uses to automatically detect friends in your photos.

“We’re working with a Silicon Valley artificial intelligence company to try and differentiate plantation forests based on their shape,” she said. “The technology learns the pattern, shape, and texture of a plantation so that it can identify them.”

Matt Hansen, who created the GLAD dataset used on Global Forest Watch, is equally optimistic that remote sensing technology – which is much of what his lab is studying – will soon be able to distinguish between natural forests and plantations.

“There’s no question that this will be automated at a global scale in ten years,” he told Mongabay. “I think it’s a cool problem, and we can solve it.”

But despite advances in remote sensing and petitions from organizations like World Rainforest Movement, it’s unlikely that FAO’s definition will change, Pekkarinen says.

“The current definition is a result of an extensive consultation with the governments and other stakeholders,” he said. “Furthermore, it has been adopted by many countries which are using it when collecting data and reporting on forest resources and their changes. Considering this, and the fact that this well-established definition has been used since FRA 2000, FAO has no plan to change the forest definition.”

Disclaimer: Mongabay and the World Resources Institute (WRI) have a funding partnership, and the author worked for WRI between 2013 and 2015. However, Mongabay retains sole editorial control of all stories produced.