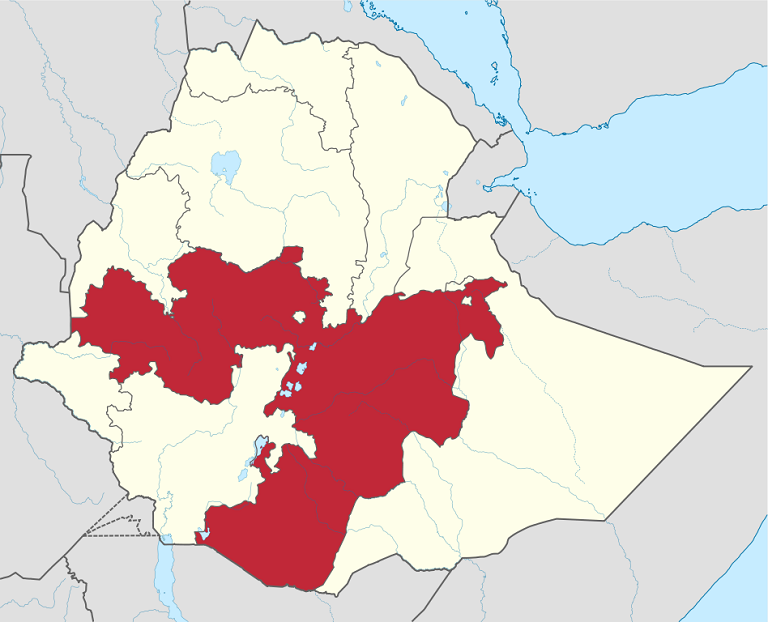

- The massive Oromia region constitutes over 34 percent of Ethiopia’s landmass and is home to more than 33 million people.

- The Oromia program will receive $68 million in various benefits through two World Bank program for the next decade.

- Ethiopia will use the program to build on existing landscape protection and project approaches to REDD+ as they scale up and finance improved land use across Oromia.

ADDIS ABABA – Ethiopia’s work to keep its environmental programs sustainable while local communities benefit from forest preservation is set to get a boost. The country’s most prominent program to mobilize resources toward its net carbon neutral by 2025 goal, the Oromia Forested Landscape Program (OFLP), is scheduled to start this year.

Ethiopia’s massive Oromia region constitutes 34.3 percent of the country’s landmass, largely in the southwest, and holds more than a third of the country’s 100 million residents. It also harbors Ethiopia’s largest concentration of biodiversity.

The $68 million OFLP project was established through two World Bank funds. One fund is for $18 million and is aimed at the restoration of forests on degraded land. The other is a $50 million fund for a program targeting carbon sequestration assessment and performance enhancement. Under the umbrella of the OFLP, environmentally-friendly businesses and industries in local communities, along with forest tourism, are also slated for development.

The OFLP will receive payments of up to $50 million for verified carbon credits against an agreed forest reference emission level from the World Bank for a decade. The forest reference emission level is part of a critical policy framework that gives countries a point to measure the results they have gained from REDD+ (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries) implementation.

An additional $18 million is under a five-year grant agreement focused on developing approaches that enable sustainable land use and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions through the BioCarbon Fund for Sustainable Forest Landscapes. The BioCarbon Fund works to combat greenhouse gas emissions that come from the land sector, including deforestation and forest degradation, and in the promotion of relevant land-use policies. The project will monitor and account for forest cover reductions and deforestation, and associated GHG emissions across Oromia by addressing causes of deforestation and degradation.

The OFLP program is designed to build on existing landscape protection and project approaches to REDD+ in an effort to scale up and finance improved land use across Oromia. REDD+ is a multi-platform program established by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. It provides a way for stakeholders and involved organizations to share experiences, lessons learned, and outcomes in their work, according to the REDD+ platform website. Some key areas the program addresses and monitors include drivers of deforestation, national strategy, safeguards, and capacity building.

Ethiopia wants to use projects like the OFLP to implement change while gaining financial benefit. The country’s current forest cover stands at about 11.5 million hectares, according to national estimates and the U.N.’s 2015 Global Forest Resource Assessment under the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). According to the FAO, a comprehensive national inventory of Ethiopia’s forests has only been done once, between 1988-2004. That study assessed all of Ethiopia and classified land use and land cover classes, growing stock, and trends. It remains the primary source of national scale forest statistics, though the African Forest Forum has planned a national-level survey of planted forests. Other available data shows that forest degradation has not slowed. Global Forest Watch numbers show that between 2001-2014, tree cover loss peaked and remained high compared to the first part of the sampling period.

According to Yitbetu Moges, Ethiopia’s national representative for REDD+ at Ethiopia’s Ministry of Forestry, Environment and Climate Change (MoFEC), real progress will require intensive collaboration.

“Reducing deforestation and improving [the] livelihood of local communities that depend on forest resources will ensure that carbon credit can be sold to the likes of World Bank, Norway and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),” Moges said. He added that most of the money will be invested in rural development as part of anti-poverty, pro-forest, rural economy-oriented programs.

The OFLP will also look at studies commissioned by the Ethiopian government and World Bank that analyze key items including drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, design of a measurement reporting and verification system, preparation of REDD+ safeguard measures, and analysis of legal and institutional frameworks for Oromia REDD+ Program.

Oromia has experience with REDD+ through the Bale Mountains Eco-Region Project (BMERP). Building on a previous program in the area, and known broadly as the Bale Eco-Region project, it covers 500,000 hectares and surrounds the 200,000-hectare Bale National Park, a global biodiversity hotspot. It was the first large-scale REDD+ project in Ethiopia.

Ethiopia’s Resilient Green Economy Strategy (CRGE) underpins the country’s goal to become net carbon neutral by 2025. The East African nation aims to accomplish key economic goals while reducing GHG emissions through efforts that include carbon trading. Such an accomplishment would involve the country doubling its forest cover to around 30 percent of its landmass, according to MoFEC.

The transition to REDD+

While Ethiopia hopes to see future benefits from the REDD+ program, the country is no stranger to carbon trading. It established the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto protocol, which requires countries to create carbon sinks by planting trees on degraded land. The 2,700-hectare Humbo CDM carbon project in Ethiopia’s south was envisaged as a carbon sink program through which carbon was quantified and brought to the international market for purchase, with the World Bank as the primary client.

According to Zerihun Dejene, environmental program coordinator at local Ethiopian non-profit consortium group PHE (Population, Health, Environment), Ethiopia has failed to make the most of CDM benefits, which allows emission reduction projects in developing countries to sell certified emission reduction (CER) credits. The CERs can be either traded or sold to progress toward emission reduction goals.

“CDM projects require approved finance, meaning the need to invest on a certain amount of afforestation project, develop and quantify the amount of carbon on sale but most developing countries can’t invest on that,” Dejene said. He added that it also requires tedious procedure and substantial investment and resources to make marketable carbon credits. Even then, a prospective buyer might reject them.

REDD+ representative Moges added that with the price of one ton of carbon having decreased from a high of $30 to less than $1 over the last decade, the lifespan of CDM naturally came to an end. Yet even though CDM was phased out when the historic Paris Agreement on climate change entered into force in November 2016, the Humbo carbon project remains. Registered in 2009 with a 30-year lifespan, it is the only significant carbon finance project currently active in Ethiopia.

In contrast to the Kyoto protocol – which puts binding commitments on individual countries – the Paris Agreement sets out voluntary carbon reduction emissions goals by individual nations. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (now called NDCs) were sent to U.N. Framework on Climate Change by individual countries instead of being used as legally binding emission targets. NDCs are expected to last from 2020-2030 and 163 countries – including Ethiopia – have set out their strategies. Countries that have formally joined the Paris Agreement have NDCs under the interim registry, which does not yet include Ethiopia.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries have cooperative agreements to sell and purchase carbon. NDCs take this one step further.

“Based on NDCs we can…determine the result of climate change as a result of this,” PHE’s Dejene said. “For example Ethiopia is planning to reduce its carbon emission by around 60 percent by 2020.”

Myriad projects

Ethiopia isn’t pinning its green economy hopes solely on a carbon trade strategy, though. It are also using other schemes such as constructing electric trains and other green energy projects. The country has already built Africa’s first electric trans-boundary railway project, the 467-mile Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway, as well as the 20-mile Addis Ababa light rail project.

But proponents say the carbon trading projects can’t come soon enough.

“At the moment we’re losing five times more forest than we’re planting,” Moges said. “It’s a crisis situation in terms of natural resource management despite all the efforts…by the government and mass mobilization of the community to [implement] reforestation and afforestation projects.”

He added that when REDD+ goes operational, revenue earned by carbon trading goes directly to the local community while helping prevent floods and droughts that regularly cause misery in Ethiopia.

“If Ethiopia is strategic in protecting its environment, natural resources like abundant water can be sold just as oil,” Moges said. “The difference being the former is renewable, and through this revenue it can power its industrialization, boost tourism, boost electricity generation thereby creating a wealthy green economy.”

Banner image: Soda volcano in Oromia region, Ethiopia. Photo by Katy Anis/UNESCO

Elias Gebrelsellasie is an Ethiopian journalist based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. You can find him on Twitter at @EliasGebre

Resources

http://theredddesk.org/countries/ethiopia

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.