- The GDELT Project is a vast open-access tool that scours and live translates news media in 65 languages to quantify, describe and map broad societal trends worldwide.

- GDELT will harness data from even minor information sources to track and understand the incidents, players and networks of wildlife crime as it happens globally.

- This iteration of the platform, set to launch this fall, will eventually incorporate information from wildlife crime literature and wildlife protection organizations on the ground.

In the eighth grade, at an age most boys spend their time outside school watching sports and playing videogames, Kalev Leetaru was delving into large-scale web mining and founding his first web company.

With his continued interest in investigating enormous amounts of data two decades since, he now heads the GDELT Project, a massive open-data platform that analyzes news media to quantify and describe broader trends in global society.

Wildtech spoke with Leetaru to learn more about the technology, a Wildlife Crime Tech Challenge Prize Winner, and its application for species conservation.

1. How will GDELT counter wildlife trafficking?

GDELT is about cataloging global human society, looking at what’s happening around the planet through the eyes of the world’s news media, specifically reaching very deeply to sources in local languages.

By the time some poaching incident makes the front page of the New York Times, it’s a pretty big incident. There’s a phenomenal amount of coverage about wildlife crime each day, but it tends to be in local sources.

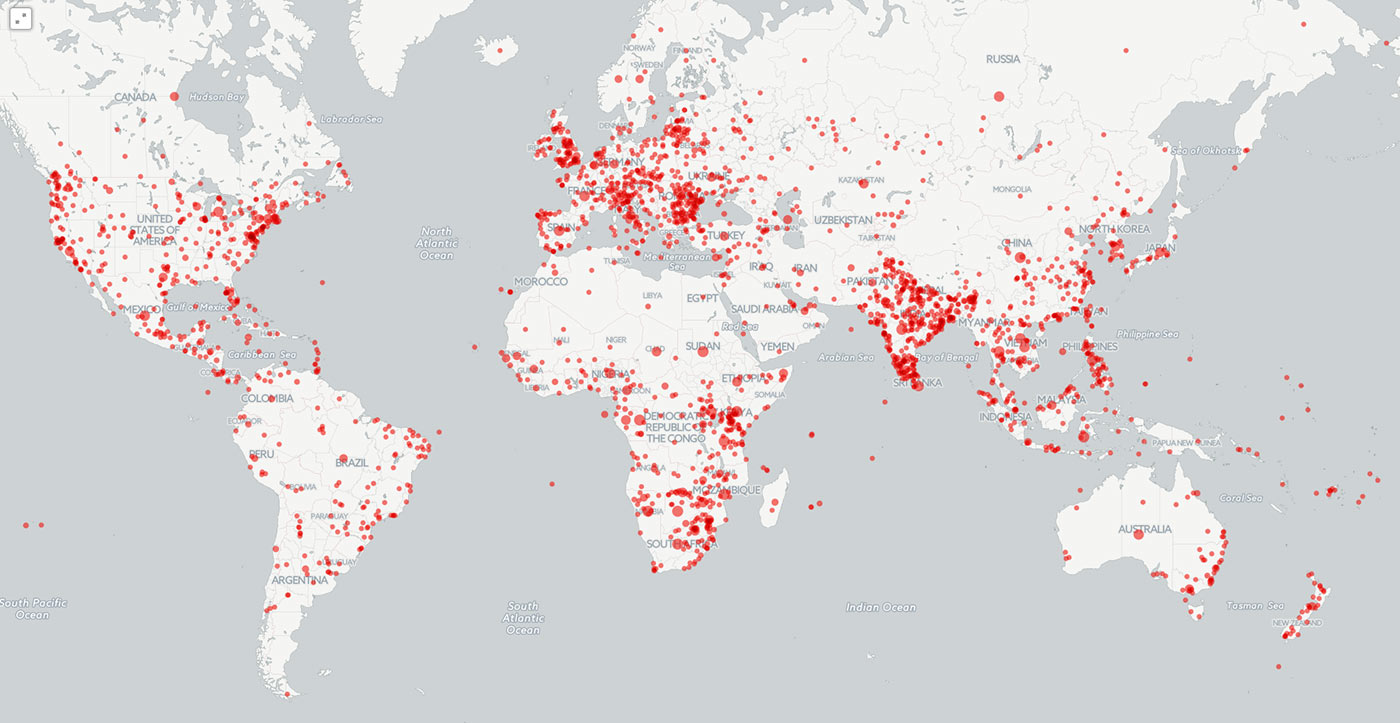

Last year, for Foreign Policy, I made a map of about three months of wildlife crime reported in worldwide media. This map went viral because it showed that poaching isn’t just elephants in Africa–it affects every corner of the world.

The initial prototype [of GDELT for wildlife crime] that’ll come online this fall is a live version of that map I did for Foreign Policy (which is static), updating every 15 minutes, showing in real time what’s happening around the world.

You click on a location for the Foreign Policy map, and you get a list of the coverage of wildlife crime in that area. The goal is to extend that to do things like network diagrams to show, when we talk about elephant poaching and the ivory trade, what locations are mentioned together in the news? What is news media telling us of transit routes? What’s reported in the news? Who are the people and organizations mentioned in that coverage and do we see connections among them? To go beyond that to things like geographic patterns. Being able to look deeply into all that coverage and eventually integrate live reporting from national wildlife services would be another interesting opportunity to combine it all together.

Being able to say, the areas we see a lot of poaching, what are some of the social cultural drivers we’re seeing there? Poaching doesn’t occur in a vacuum.

The goal of GDELT is a) provide a live feed of what’s happening now, b) to provide these deeper analytics on top of that so you can understand everything from influencers in media coverage to insights being captured within that coverage.

2. Who do you envision using GDELT in the fight against wildlife crime?

There’s a variety of audiences. That’s one thing that makes it so powerful. It’s not a technical tool designed for one particular use. It’s a broad platform with many different applications.

For wildlife officials, you could get that 30 thousand foot view. If you are a counter trafficking officer, your day-to-day is your particular assigned area of responsibility. You know explicitly well what’s happening in your area. But you probably are not very aware in the region, nationally or globally because there’s little data.

For policy officials, that ability to document and show [trends] in a nice easy-to-use map.

From a communications and policy standpoint, to look at a map like that and see there’s a dot everywhere across the world, over here in this country they’re prosecuting this, in Ukraine local police arrested a couple of guys for illegal fishing in the middle of a warzone. That’s a really powerful thing to see how poaching’s affecting the world around us.

3. Where exactly does GDELT mine data from?

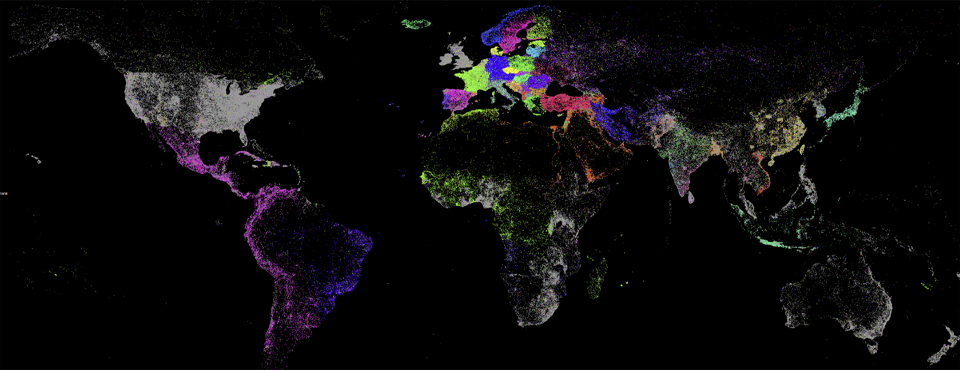

[Our] primary sources are worldwide news media—print, broadcast and web. Everything from major international sources to small newspapers or broadcasts. Broadcast is crucial in many parts of the world. So much of poaching reporting is local sources in local languages. It supports about 100 languages, of which 65 are live machine translated.

Another source is a collaboration with the internet archive to monitor about 100 television stations in the US that allow a look at what’s trending here. That’s powerful to look at the duality of what’s being reported around the world and what are Americans seeing.

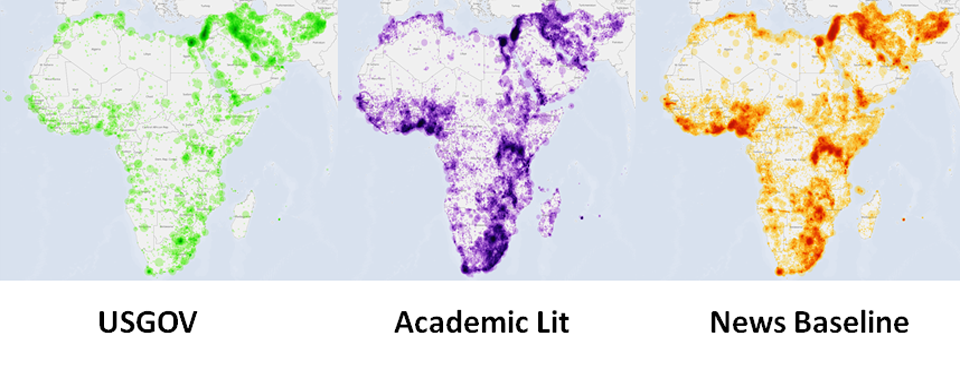

The 21 billion words of academic literature spanning 70 years allow you to contextualize [poaching]. This gives you information to understand who is an academic expert who might have some unique insight to that.

Social media is not used. If you want to know what’s happening in a lot of the areas hard hit by poaching, social media is less useful. A lot of poaching is not speculative. Usually there’s an established pipeline with buyers and distribution networks. Social doesn’t reach into these areas. And social is increasingly off limits. As Twitter has largely stalled around the world, Facebook is really expanding as a communications platform. The majority of that conversation is private and not accessible to mining. We talk about social media being this panacea of understanding society, but often fail to recognize that in parts of the world I deal with, counting up how many tweets per hour mentioned “tiger poaching” has very limited utility.

4. What does GDELT use to ensure accurate translation?

At 65 languages, you’re looking at immense complexity across the world. Machine translation is far from perfect. But what you’re interested [in] here is primarily factual information. Machines are pretty good at that type of translation. When you’re getting to this sarcastic flowery poetic speech in this Russian anti-government editorial, machine translation can struggle.

Machines can peer through and give you a basic report of what’s happening. Most of the time, that’s all you need, to know there’s local reports that something’s occurring in this area. If it becomes important to understand the nuance of that, to say the machine’s algorithms say this seems to be saying they shouldn’t stop poaching, that poaching’s good for the economy, you send that to a native speaker to verify.

5. How will the contextual information you talked about fit into the interactive map?

That would be the second layer. If I were one of the grand challenge winners, the goal would be to leverage that funding to expand and leverage this dataset. Imagine being able to click on a location and see a dot that says there’s a lot of elephant trafficking occurring here and get information about common practices here. Bushmeat? Warring social factions that contribute to instability that allow poaching to thrive? Are natural resources for economic exploitation or national treasures to be protected?

Also, if you’re interested in the psychology of poaching in this area, being able to recommend that literature and say, here are three papers that get at why people poach in this area. Then linking to those authors and saying, here are the three people most heavily cited when it comes to poaching in this area.

6. Are there any other technologies that could function as GDELT does and serve the same purpose of combating wildlife trafficking? If so, what are GDELT’s pros and cons in comparison to them?

One of the reasons for leveraging GDELT is there are no alternatives to reaching this deeply across the world. Google News is a wonderful resource, but it doesn’t have quite the reach into the farthest corners of the world and especially the ability to look across languages. GDELT is live translating all this material. All you have to look for is “poaching of tigers” and you’re getting tiger poaching across all 65 languages, versus running 65 different queries and not being able to do anything if you get a document in Thai. Language no longer becomes an obstacle to being able to put that dot on the map and say something big is happening here.

The goal is to harness all this data that’s already out there. So much of the data we need’s already there in a form we don’t have ready access to, scattered across millions of news websites and outlets across the world in local outlets in local languages.

7. How much wildlife crime news do you think GDELT would be missing? Do you plan to somehow incorporate this data into the tool?

I’ve been having conversations with groups working with local wildlife protection officers on the ground. I’m interested in finding local organizations on the ground that can ground-truth [the news] and say here’s the actuality of what we’ve been finding. It’s useful to calibrate what are we seeing in the media compared to what’s happening in the ground. Even when there is bias, they tend to follow a very specific formula, so you can calibrate for that. More importantly, from the standpoint of counter-trafficking, it’s very important to know what’s being missed, to say only 10 of the 30 big finds we’ve had have gotten media coverage. That tells you we’re not doing a very good job of ensuring the media’s covering this stuff. I’m very interested in local partnerships.

8. How did you come up with the idea of GDELT and decide to apply it to counter wildlife crime?

One of the things I’m very interested in is how we model and understand global conflict, getting down to the level of things like protest and violence. That required catalogs, mathematical models to describe human society. You need to have datasets—to make timelines, to quantify human society, requires this incredible data that did not exist. The genesis of GDELT was to say, how do we quantify human society across the world?

The idea of GDELT is, there’s so much data out there. How do we bring together this amazing volume of information in a single actionable space? The goal is an open-data platform others can build upon.

Last year, there was some large poaching incident in the news. It made me wonder, every time I hear about wildlife crime, I hear about elephants in Africa. When I came across the USAID call for the wildlife tech challenge, it was a perfect match to see there’s a whole program here.

We have immense data, immense computing power. But there aren’t many people that have the skillset to bring those together and not many interested in this. My interests are the grand challenge problems.

Wildlife crime is a perfect fit. How do we revolutionize how we understand wildlife crime in terms of what’s happening [and] build media datasets to think about it from different dimensions? By creating maps like this, we can observe patterns of what’s happening around the world, [such as] what are these transit routes? Or let’s say there’s a major ivory bust in a country and they take down a major distributor, do we observe any changes? Before that map was made, I couldn’t find another map where someone had created a map of a couple of months of wildlife crime across the planet. There aren’t many tools that allow us to look holistically across all that. I’ve always been interested in how we try to understand the planet, so this is the perfect application.