- Created in 2012, Latest Sightings is a mobile app and social network with a community between 450,000 and 500,000 people.

- Latest Sightings allows app users to report real-time sightings within South African parks and promotes conservation and education through online platforms.

- Wildlife sighting apps have faced recent criticism, but Latest Sightings CEO and Founder Nadav Ossendryver explains that these apps are saving wildlife and globally educating millions of wildlife enthusiasts.

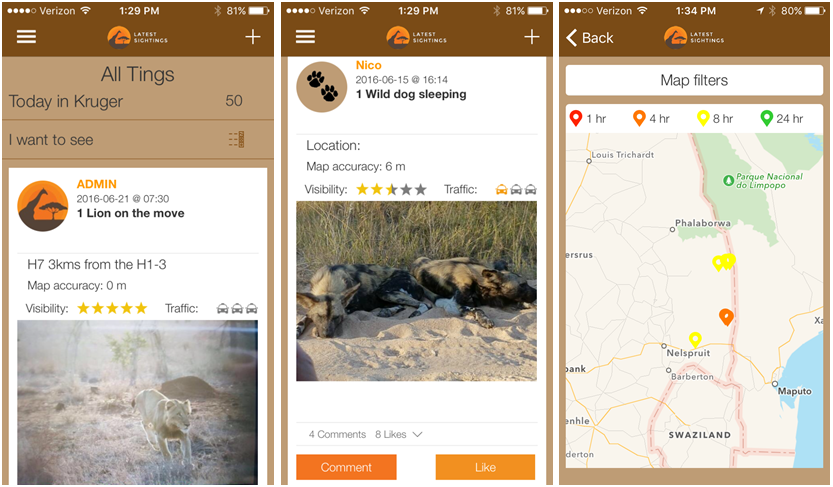

If you’re a frequent or soon-to-be visitor of Kruger National Park in South Africa, you might just consult your smartphone, instead of a guide, to help you see the Big Five. Developed in 2012, the Latest Sightings app provides real-time updates on live animal sightings within South African parks.

For wildlife enthusiasts, the app invites mixed feelings. Latest Sightings gives park visitors the opportunity to easily hone in on exactly what they want to see, from photos taken by other visitors. Seeing predators, birds or beautiful scenery is as easy as filtering through the app. For some, this is a welcome aid in enhancing a safari experience. But others, like the officials at SANParks, are blaming wildlife sightings apps for an increase in speeding, roadkill, and general irresponsible behavior.

We spoke with the CEO and founder of Latest Sightings, Nadav Ossendryver, to learn more about the app, the most watched YouTube channel in South Africa, and how mobile platforms can support conservation, as well as his opinion on the recent vocalization from SANParks.

How and why did you develop the Latest Sightings app? What was your initial goal when developing the app?

I created the app in 2012 when I was 15. I spent 3 weeks, 24/7, watching videos and reading tutorials on Google and YouTube, learning how to develop the app. I wanted to create an app that shared what everyone was seeing so we could see more wildlife.

I wanted people in the park to experience more wildlife, but also showcase wildlife to people who weren’t there. On our YouTube channel, the top countries are the US, UK, India. We have a lot of followers from outside South Africa.

What is different about Latest Sightings in comparison to similar apps?

In South Africa, there are one or two different apps trying to do the same thing. With Latest Sightings, I like to build up the community. Our community is loyal and a big part of why we continue to grow. People are connected to Latest Sightings, the app and conservation. We have a great app, but we also have a great community.

How did you create such a successful community?

I took interest in anyone who was part of the community. I didn’t just put out ads or promote the page on Facebook. I spoke with each person downloading the app. I took care to speak with each person joining. They felt we cared, and they fell in love with the community. At the end, it wasn’t just me, it was friends they’ve made through the app. It was definitely the interaction and human element.

Now, altogether, across all platforms, our community is about 450,000 to 500,000 people.

You’re collecting a lot of data on animals and where they are in the park. What do you do with all of that data? Is data shared or made available to researchers?

Our biggest community is in the Kruger Park. We are slowly but surely starting in other parks, but I’ll give Kruger as the example. We work with a lot of research projects that operate in Kruger Park with endangered species like wild dogs, martial eagles, pangolins, and ground hornbills. Those species are endangered due to poaching, other animals killing them or diseases; they are also naturally elusive, so they are hard to find.

When you have one research team looking for a pack of 20 wild dogs, it can take months. We get the community to find these dogs, and then the researchers can go to the sighting and do what they need.

We keep a database; once a month, we send the information to various research projects so they can extrapolate the data. In 2015, probably the best example, the Martial Eagle Project got 50% of all of their information from sightings that Latest Sightings sent in. So 50% of research was because of our community and sightings we shared.

We never sell data. There are different revenue streams we look at, and data is not one. The researchers need it to help save animals’ lives. Whatever they’re researching, whatever they’re doing, [the data] is going to help. Obviously we look into if they are reputable and if they are actual research groups. Once we confirm their research is valid, we provide whatever information they need.

Besides reporting where animals may be or giving data to researchers, are there other methods you use to promote conservation and animal well-being?

The other method that excites me all the time is when people report injured animals through the app. Unfortunately, we occasionally get reports of animals injured by human interactions, especially snares around their necks. Snares don’t kill animals immediately, so it sometimes gives the animal enough time to be seen by our community, which, when reported, we can instantly send to the relevant people. In the app, we have a place where people can describe the sighting, so people usually report the injury there.

When an injured animal is spotted, park goers should send reports straight to the park authorities. But a lot of the time, it’s tourists that don’t know where to report. So Latest Sightings is the first place to send these alerts; we forward the sighting on to the right people – rangers, vets – and that allows the animal’s life to be saved. We have had many cases of wild dogs and hyenas’ lives saved.

Does that mean someone is monitoring the live updates?

Yes. We go through each sighting every single day to see if there is an amazing sighting, something really rare, or if there is an injured animal. Big sightings, like lions and their kills, sightings that could be there for days or hours, we confirm those.

Recently, wildlife sighting apps have come under criticism, with SANParks saying they are responsible for an increase in roadkill and speeding in parks. What is your opinion on the recent vocalization from officials at SANParks on app use in South African parks?

Park attendance has increased by 25% in the last nine years. If the attendance is increasing by 25%, that means everything is going to increase – speeding, roadkill. There are 1.5 million visitors a year in Kruger Park, a park that has had the same road coverage for 20 years . The numbers are increasing, and there’s less space to fit all of those people in. I don’t think apps are increasing bad behavior.

Every time people enter the park, they get a pamphlet with the rules. It’s impossible to make sure everyone behaves properly. But, I’m sure there are ways we can ensure more people behave.

There is no need to ban the apps; they’re a brilliant thing for conservation, education, marketing and tourism. Through Latest Sightings, 320 million people have thought about South Africa’s wildlife. The policing aspect, I think, can be done. We just need to work together to find solutions.

Do you work directly with the authorities in the parks?

Yes, in some aspects. The rangers and vets, a lot of them are part of the community. A lot of them look out for injured animals. The people that actually run the park are government, so it can be hard for us to get in touch. We approached them recently to meet and strengthen our relationship.

How can the app be used to make park goers and the community more aware and feel more of a responsibility toward protecting wildlife?

Our app is four years old, but our social media presence is bigger than [our following of] app users. On our social platforms, we highlight our latest sightings. We try to create awareness and ask our community to share rare species sightings. Like Martial eagles — people don’t think they’re rare because they see them often. We ask people to send those sightings in because they are endangered.

We also have about 3,000 people in our WhatsApp group. Every morning we post rules like don’t litter, don’t speed, don’t get out of your car, but also report these sightings because they go a long way for researches and can help save animals lives.

Latest Sightings makes money off its YouTube videos and will even pay contributors for their videos if they go viral. Can you expand on this.

We haven’t built Latest Sightings as a nonprofit. When I was 15, I had no idea I would make money. But to grow this community and develop an app, it’s expensive. I got a few people to help me with funding at the beginning, but we wanted to make some revenue.

The one place that is working is YouTube. If we get a viral sighting, we sell it to different news agencies or YouTube. If it’s not our sighting, we share whatever we get to the person who posted the video through our partner program. It’s nice because it helps us pay salaries and helps people who enjoy the park get a reward out of it.

We started the partner program because our videos were going extremely viral, we were starting to earn money off of the videos and we thought, we have to share this, it’s not ours. We have to reward our users. We were going very viral before the partner program existed, before the revenue share existed, but a lot of people have used it as an incentive. For many people, when they do film something amazing, they share the video because we can make it go viral, not because we can pay them. A lot of people just want their videos to be seen. The average view on YouTube is around 27 views; our average on our channel is approximately 1.1 million views. The biggest incentive for us and our site is that we are reaching 200,000 people every day. That’s 200,000 people every day that are learning that much more about wildlife.

How can conservation groups use a platform like YouTube to create revenue?

It’s a standardized format; there are millions of people that use YouTube as a revenue stream. You have a video; YouTube puts ads on the videos. For every view you get, you earn a small amount of money. If you get millions of views – we have 321,000,000 – those cents add up. It’s a good model for lots of people, and it’s something we started when we realized we were getting big on YouTube. It’s the biggest South African YouTube channel.

You have to have a person run the YouTube channel. You can’t just put the video up and hope for the best. This afternoon we released a video and spent an hour on just making sure the thumbnail is perfect for someone to click on. Something like that can increase your views or make your channel completely irrelevant. You can have a YouTube channel easily, but it’s making the channel work that we have managed to learn.

Why won’t the app let users tag rhinos in parks?

When I started my community in 2011, poaching of rhino had started increasing and getting bad in the park. People were not wanting to share rhino sightings, photos, locations. If I wanted to build my community and gain their trust, I could not post rhino sightings. It was an easy decision to make because it made sense. So if anyone tries to tag an animal with a name that doesn’t exist in our database, it won’t allow them to.

Is there a concern for animal safety in regards to poaching when animals are tagged in real-time sightings?

We have a great community, and people are learning to love wildlife through sightings we share. Sharing sightings of these various animals is helping them as opposed to helping poachers.

For example, [with] tagging a lion in the app, so many more good people know where the lions are, as opposed to one or two poachers. It makes it harder for poachers to go [to] those areas because a lot of people will know there are lions in the area.

When we share sightings, videos or photos of animals, people are learning about them. And when you learn about something, you learn to love and appreciate it, and perhaps be more proactive toward saving it.

I went to Vietnam, and all people [there] know about rhinos is the horn or that they’re being poached. They don’t know what they are as animals. In a tourist section of Vietnam, there was a huge billboard that said, “Don’t Buy Rhino Horns,” [with] just a silhouette with the horn. It doesn’t mean anything to a person who has never seen a rhino. If they could see the eyes, ears and nose, people could connect more.

I want to post rhino sightings, maybe not with locations in the beginning. To start getting people all over the world to understand these rhinos are animals, and teach them that when you have a rhino horn, you’ve killed a rhino.

Out of respect for the whole South Africa, we won’t post rhino sightings, but it would do a lot more good by educating the world about our animals. There is no other platform like this for real-time daily updates on animals.

Is there a growing concern that the threat of poaching in Kruger will shift toward other animals (i.e. elephants or lions)? In that case, how would Latest Sightings respond?

Elephant poaching in the northern part of Kruger is happening. There is also not a single cell tower, so we don’t get reports there. We have been going for five years, and still the only animal being severely poached is the only animal we don’t report. If elephant poaching gets extremely bad, like [with] rhinos, then we will see what we will do. Hopefully we won’t get to that stage.

Take, for example, the pangolin. It’s an endangered animal, and researchers told me they want us to continue posting because people don’t know what a pangolin is. A month later, we get a sighting; people are now learning what a pangolin is. It’s brilliant to educate.

Are there improvements you are hoping to see?

We are always working on features for the app.

For people in the park, all sightings are relevant because when you’re in an area you want to see all sightings. But people in America aren’t as interested in sightings without photos or videos, as a person in the park [would be]. So we now created another field that will tag the most trending sightings in the past 24 hours, and those will be ones with photos or rich media so it’s more entertaining for people around the world.

We are also looking at being able to switch off photos. If you’re in the park, you don’t want to use your bandwidth or internet to download sightings.

What are your biggest technological challenges?

Cell coverage is a problem. We have addressed the problem by making the app native to each phone. It’s built in Android’s native language and in Apple’s native language. The native language doesn’t use internet to run the app.

Without signal, you can still use the Latest Sightings app. You can post sightings; the location is accurate to 5 meters. When you get signal, you can update the data and upload your sighting, and it will download all newly reported sightings. If you go without signal, all sightings you previously downloaded are still present on the app.

Have you ever had problems with the app?

All the time, unfortunately. We get a lot of hits; sometimes the server can’t handle it. We are moving to a stronger server that we hope can handle the traffic and be faster. It is something very frustrating. Servers are extremely expensive, but we need it because no one likes when the server goes down. Our software is really good, and people find different uses for it. We are in discussion with other groups that want to use the app for reporting crime, fires, anything that needs live reporting. We have software to accommodate it. It’s complicated, but works beautifully in the front.