- Eyes on the Seas helps law enforcers at port swiftly detect and prosecute fisheries violations in vast remote marine reserves through a centralized virtual watch room analyzing many layers of data.

- It seeks to counter the severe negative environmental and economic impacts of illegal fishing to protect migratory fish species and their few remaining near-pristine marine habitats from exploitation.

- As the platform evolves, more countries, fisheries management groups and retail organizations could adopt it to monitor commercial fishing vessels’ movements and avoid supporting illegal catches.

Approximately 120,000 fishing vessels sail the oceans at any given moment, many fishing illicitly. Globally, one in five marine fish caught ends up on a $23.5 billion black market. Unrecorded unregulated fishing has depleted fisheries to critical levels and prompted projections that all fisheries will collapse by 2048 if business continues as usual. Yet industrial pirate fishing off the shores of developing nations and in far ocean recesses persists surreptitiously, as authorities cannot survey all corners of the seven seas to stop the plunder and protect marine species worldwide.

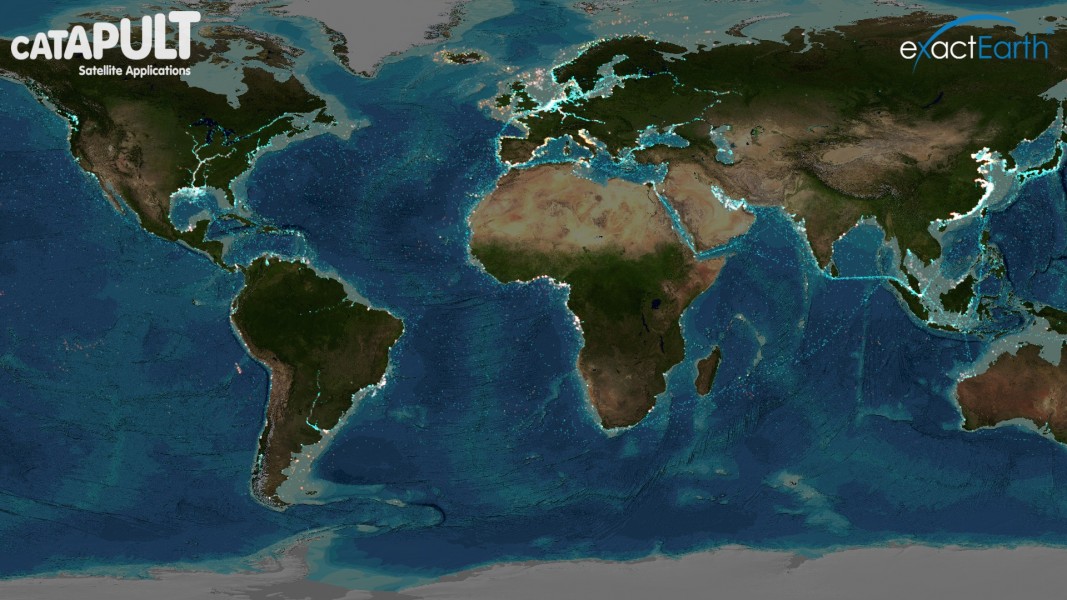

Project Eyes on the Seas is a surveillance platform that helps law enforcers at port swiftly detect and counter fisheries violations in expansive remote marine reserves through a centralized virtual watch room (VWR). It synthesizes and analyzes layers of information from different maritime tracking systems, real-time satellite images, proprietary databases, international fishing and marine reserve borders and environmental and oceanic data including depth and temperature.

The system analyzes the compiled data and alerts analysts of suspicious activity, so that government enforcement action can focus on areas historically or currently exhibiting illicit fishing. It allows law enforcers to share information regarding illegal fishing operations, substantiate a case against them with evidence from analysts, track them into a port or enforcement vessels’ reach and prosecute them. The platform aims to protect tuna, marlin, swordfish and other highly migratory fish species, as well as their open-sea habitats, from exploitation globally.

“Eyes on the Seas is holistic,” said Tony Long, Director of the Pew Charitable Trust’s Ending Illegal Fishing Project. “Trying to bring everything together in one place in order that we can only look where we need to find illegal fishing brings down the cost, makes it more effective, allows people to target the assets they’ve got–whether it be aircrafts or vessels–or just prepare port officials for when [suspicious] vessels come into port.”

How it works

Like Global Fishing Watch, a fisheries monitoring tool developed by Google, Oceana and remote sensing and digital mapping nonprofit SkyTruth in 2014, Eyes on the Seas uses the Automatic Identification System (AIS). AIS is a GPS-based system through which ships signal their positions and prevent collisions. The project uses it to distinguish between non-fishing and fishing vessels. Eyes on the Seas stands apart, however, because it then integrates multiple data sources to provide robust reports backing enforcement against unlawful fishing boats. For instance, it alerts officials and taps into secure radar data to pinpoint a boat’s exact location if a captain with questionable motives disables its location-broadcasting transponders. It even uses satellite imagery to detect vessels escaping its other monitoring systems.

“This system is building on layers of data, automatic analysis, algorithms and a threat index. As you add up scores against the vessel’s activity, you can prioritize how bad this vessel might be, like a naughtiness score,” explained Long. “If it’s not transmitting on its transponder effectively, if the identification number doesn’t quite tally, if it’s coming from a port that’s renowned for illegal fishing, all these will make the vessel a higher priority for watching.”

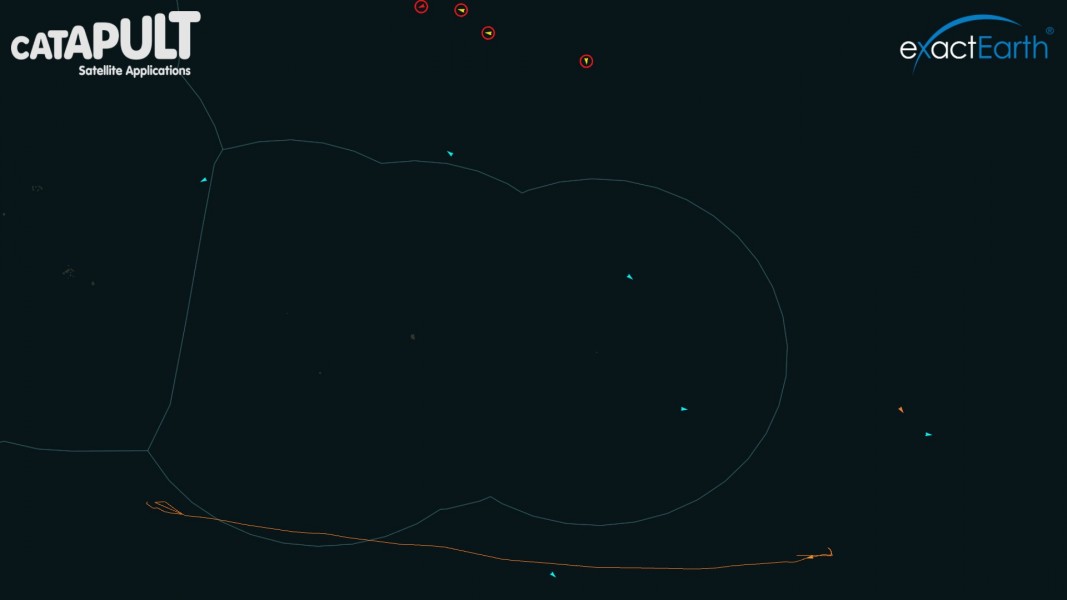

A single analyst in the VWR in Oxfordshire, England, can follow each vessel in a marine reserve as a moving point on a world map and determine whether it is trespassing. Using algorithms, the VWR receives an alert when a ship crosses a virtual geofence and enters a reserve or otherwise restricted waters or new economic zone. The VWR accesses an extensive database to identify the ship’s owner, history and country of registration and monitor its movement and speed. If a ship that shouldn’t be fishing slows to five or fewer knots or exhibits other movements characteristic of fishing, it triggers an alert. The system also tracks reefers, refrigerated transhipment vessels transferring illegal catches in areas banning fishing, by informing officials when two ships meet for over thirty minutes.

Whereas Global Fishing Watch disseminates unclassified information to a public audience, Eyes on the Seas’ access is limited to governments and industries due to security or commercial licensing restrictions. One such confidential class of data comes from the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS), a collection of constant privacy-protected encrypted vessel tracking satellite communications.

“This system is built on the level of analysis required to achieve enforcement, so we don’t feel it needs to be publically available,” said Long. “The value is in the proprietary data being analyzed properly and presented to people who can actually take action.”

Skytruth President John Amos believes that by guiding law enforcement, Eyes on the Seas complements Global Fishing Watch’s mission of building public awareness about commercial fishing’s damaging intensity.

“Governments and industries historically and repeatedly underperform in the absence of public pressure, so we need the public to set a higher bar,” he said. “Eyes on the Seas is the toolkit that makes it possible for them to meet and exceed those public expectations.”

The VWR also provides a more effective means of surveillance than conventional boat or aircraft patrols. Boats are relatively slow and vulnerable to attack, and planes are too high up for detailed monitoring.

Launched in January 2015, Eyes on the Seas is a collaboration between Pew, U.K.-based technology center Satellite Applications Catapult and the island nations deploying and funding it. Long had challenged Catapult to create a comprehensive classified surveillance system that was more equitable and cost-effective than alternatives from large private for-profits, patchy unlinked global surveillance networks and free but not self-sustaining or highly effective models.

In 2015, the British government established the 830,000 square-kilometer Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve, the largest one in history, in the waters of the southern Pacific overseas territory. Eyes on the Seas has been monitoring vessel activity here since January of that year.

“Several contacts have been passed to the British government and flagged as suspicious,” said Long about surveillance outcomes so far, noting that the details are classified. “The British government is investigating those tracks in order to establish what they were doing and who owns them. That’s working well.”

The technology has also been successfully tested in waters surrounding the Pacific island of Palau and the Polynesian islands, such as Easter Island off the Chilean coast. It’s ready for deployment in these nations if they decide to adopt it. The not-for-profit project presents poor island nations, often disproportionately plagued by unregulated fishing, maritime surveillance data they would otherwise be unable to afford.

“That’s the crux of the vision, that any port anywhere in the world will have access to the information they need to make the right decision about a vessel trying to enter,” pointed out Long. “This system can represent a much more cost-effective system than putting ships at sea to patrol areas where they don’t know where vessels are. It’s probably less than a quarter of the cost of putting one vessel to sea.”

Challenges in enforcing international fishing laws

Eyes on the Seas faces several significant obstacles. AIS is inexpensive to set up, run and maintain, but because it isn’t compulsory for all ships, numerous fishing vessels don’t have it (read about how researchers are arguing for making AIS mandatory to curb unauthorized fishing here). Additionally, captains of unauthorized fishing boats and legal ships can turn off their AIS to evade law enforcement or avoid revealing prime fishing spots to competitors. Criminal vessels can also falsify data transmitted by AIS, including ship name, type, and location.

The other sources of data that Eyes on the Seas accesses also have limitations. The tamper-proof radar that it taps into to track non-transponding boats does not give as detailed information over as comprehensive an area as AIS. In addition, capturing boats moving at several nautical miles per hour through satellite imagery is difficult. The time lag between when you order an image and when the satellite captures it is usually over 10 hours, and could even be days, so imaging a sailing vessel that’s constantly changing course and speed is problematic. And repeatedly surveying large swaths of the ocean using numerous commercial radar and high-resolution optical images covering tiny patches is still expensive.

According to Long, another challenge facing the platform is the prevalent perception that it’s not worth the financial investment, stemming from public undervaluation of the power of this platform and of the environmental and economic gravity of unregulated fishing.

What’s more, for the project to succeed, its intelligence must be supplemented by an intricate and swift synergy of analysis in the VWR, effective communication of suspicious activity to authorities, and well-coordinated law enforcement to apprehend and prosecute offending ships. Mismanagement and corruption would render the system ineffective.

Still, Eyes on the Seas hopes to expand in the near future according to emerging technologies and changing needs. Its developers envision its implementation across more marine reserves and the export of the VWR to additional time zones for regional monitoring instead of having analysts working through the night in the UK. The technology could incorporate new data sources, including more satellite imagery, various kinds of optical imagery, imagery from unmanned aerial vehicles, radio broadcasts and crowdsourced photos and sightings from any ship or aircraft.

Lastly, a trial is set to launch this month to prove that the platform is beneficial for retailers auditing fishing vessel activity to understand their fish’s origins, demand transparency and practice due diligence. Long explained that if retailers refuse trade with untraceable vessels, it will force more ships to transmit their position. This could lighten analysts’ load and draw attention to possible offenders, block their profits and facilitate prosecution. Retailers could gain access to the tool later this year.

As more countries, fisheries management groups and retail organizations pay attention to commercial fishing vessels’ movements and adopt Eyes on the Seas to avoid supporting illegal catches, they could help conserve some of the world’s few remaining near-pristine marine ecosystems.