- ICARUS tags and satellite will track animal movements and migrations from the International Space Station, which travels at a lower (closer) orbit than satellites and enables transmissions/communication from lower-energy tags.

- ICARUS tags will be roughly 5 grams—small enough to tag animals weighing 100 grams—with plans to develop even smaller tags to study insects in the future.

- Project testing begins this year; the system will launch in 2017 and will open to the scientific community in 2018.

Icarus, from Greek mythology, flew too close to the sun on artificial wings and fell to his death in the ocean below. Many interpret this story as an example of pride and arrogance, but some physicists believe the story conveys a different lesson: One should be curious, courageous, and fly as high as one can get. Migratory birds, from large raptors to tiny warblers, do just that – soaring across continents and oceans and returning to their breeding grounds using routes that still mystify us.

The ICARUS Initiative is poised to help researchers explore the full extent and patterns of the migrations of even smaller-sized species, by creating and linking up a smaller, lighter and lower-cost satellite tag than currently exists.

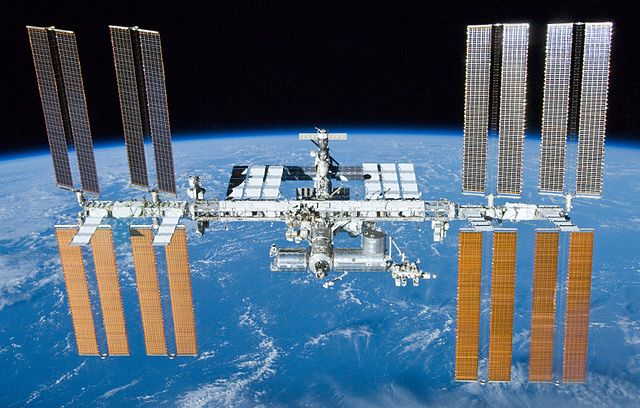

The International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space (ICARUS) Initiative, headed by the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology (MPI) and supported by Russian and German space agencies and other collaborators, is dedicated to establishing a wildlife radio receiver for tracking the large-scale movements of animals. Astronauts will deploy the system on the International Space Station (ISS), which circles the earth at 400 km, a relatively lower orbit than satellites.

The development team hopes that this new not-for-profit tracking technology will allow scientists to answer questions concerning (1) the dispersal and migrations of animals, including those that damage human resources (i.e. food), (2) the global spread of diseases by animals, (3) animal behavior in changing environments, and (4) the areas needed for survival by a suite of different species.

Tracking Animals from the International Space Station

MPI is collaborating with SpaceTech to develop the ISS on-board equipment for ICARUS as well as the transmitter that sends the tracking information from the tag on the animal to the receiver. The equipment on the ISS consists of three receiver antennas, a transmission antenna and an electronic unit. The three receiver antennas can detect up to 500 tags in 24 hours between 58 degrees North and 58 degrees South latitude.

The 5-gram ICARUS animal tag will contain a set of sensors designed to enable researchers to track an animal’s movement patterns and vital parameters. The tag will communicate with the sensors on the ISS from up to 800 km away and will log acceleration, local temperatures and GPS locations. The tiny (22 x 13 x 7 mm3) tag enables researchers to tag and monitor animals as small as 100 grams and has an expected lifetime of one year. For more details, see SpaceTech’s data sheet.

The transmitter sensors acquire the animal’s GPS position and velocity, 3D-acceleration, 3D-magnetometer to detect its direction (or heading), and external temperature data and can store around 2 GB of information. The data acquisition rate varies, depending on overcast or sunny conditions; sunny conditions produce rapid GPS fixes, while overcast conditions lead to approximately 6–12 GPS fixes per day in addition to sensor data. If the tagged animals are in Artic or Antarctic regions, the data is stored in the transmitter’s memory and sent to the ISS when the tag is within 60 degrees North and South latitude. Movebank, a free online databank hosted by MPI, stores the data collected from the animal migrations and movements.

When the ISS ICARUS equipment has a read on a tagged animal, such as a bird in flight, the transmitter will switch from its energy-saving mode to send the location, movement and vital parameters data within a few seconds to the space station. Due to the relatively close proximity of the transmitters to the International Space Station, transmitting signals will use less battery power than transmitting to satellites.

After the planned launch in the spring of 2017, researchers should begin to improve their understanding of the movements of tagged animals. In email correspondence with Wildtech, Keeves explained that, “non-binding pre-orders for basic ICARUS tags are being accepted now with the aim to provide sufficient numbers of tags immediately after the system is operational in the early summer of 2017.” Costs of the basic tag will range between approximately $560 and $780 (500-700€), depending on the number of pre-ordered tags, while the annual service fee for the ICARUS User Data Center will cost roughly $170 (150€) per tag.

ICARUS developers aim to eventually create tags small enough to track insects and other tiny animals to understand and track the relationships, movements, and lives of as many species as possible. This revolutionary step in animal tracking could be a vital tool for conservation and human health.

Several technical challenges identified by SpaceTech include: communicating simultaneously with a host of transmitters, miniaturizing tags to track small animals and insects, logging a tagged animal’s physiological state and environmental conditions and extending transmission battery life to cover complete animal migration cycles.

A Race Against Time

Researchers are hopeful and cautiously optimistic that the new technology will improve their tracking success.

Dr. Lisa Davenport from the Florida Natural History Museum and her colleagues in Norway, UK, Oklahoma, and Brazil, study intra-tropical movements of Amazonian waterbirds. One such bird is the black skimmer (Rynchops niger), which migrates long distances during both breeding and non-breeding seasons, and for one subspecies, even soars over the Andes mountains, above 16,000 feet (5,000 meters). The migration patterns of black skimmers are still largely unknown, and Davenport and her colleagues are gaining a deeper understanding of their trans-Andean and trans-Amazon migratory routes with the use of ARGOS satellite tracking system.

In an email correspondence with WildTech, Davenport explained that “we are in a race against time to learn baseline information about intra-tropical migrants in a reasonably untouched ecosystem, but development pressures are huge for the Amazon, and we are clearly on the cusp of major changes.”

Her research team has realized that “at present, there is no system other than satellite telemetry that can really help [us] study avian migration across the Amazon Basin,” but the high cost of satellite units prevents her team from tagging a large sample of these birds.

Davenport and her team are also enthusiastic about the possibility of 30-meter resolution GPS location data with ICARUS compared to “Argos locations, which can be from 250 meters to many kilometers’ resolution. So, for example, with the skimmers we could do a better job learning just where they feed (lakes of different types vs. river, for example) and also exactly what routes they use during migration. All very exciting if the system lives up to its promises!”

Davenport added that “at that price structure, [this system] is very attractive to projects like mine on the skimmers and similarly sized water birds in the Amazon. If the system lives up to its promises, I see it greatly expanding our abilities to study avian migrations in detail.” With the lower costs of the ICARUS system, Davenport would be able to study more birds with her current budget and therefore “better document variability within and across years.”

We’d love to hear from other researchers who have tracked large-scale migrations or are looking to do so. What limitations have you faced? Leave a comment or visit the Forum to let your colleagues know.

If you are interested in learning more about the ICARUS Initiative, please visit their website.