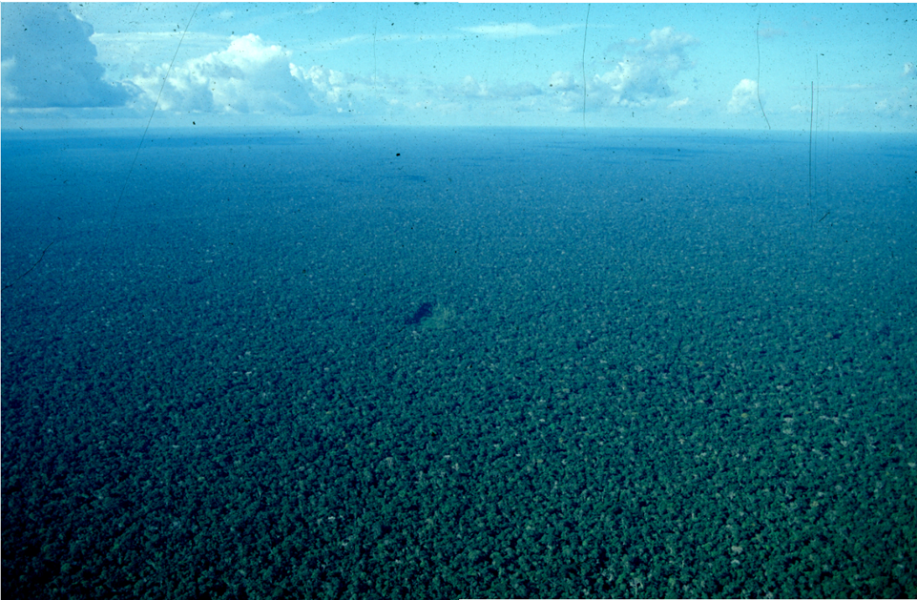

- A significant amount of the Amazon rainforest’s above-ground carbon stock could be lost if key seed-dispersing species continue to be over-hunted — even if the forest is protected from all other threats.

- Over-hunting of larger mammals like tapirs and monkeys can lead to declines in the carbon content of the Amazon.

- 2.5 to 5.8 percent losses in above-ground biomass on average could be lost, according to researchers.

We know that deforestation threats like timber extraction and wildfires are bad for the stability of the global climate because they cause massive amounts of carbon stored in forests to enter the atmosphere.

Now research shows that there is also a climate cost to hunting wildlife species to extinction in the world’s tropical forests, which are estimated to store as much as 460 billion metric tons of carbon.

The authors of a paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences say that a significant amount of the Amazon rainforest’s above-ground carbon stock could be lost if key seed-dispersing species continue to be over-hunted — even if the forest is protected from all other threats.

Amazonian wildlife has been declining due to habitat destruction and over-hunting since the 1950s, but until now there hasn’t been much research done on the status of wildlife populations in hunted forests that have otherwise been left intact and kept free of human disturbance, according to Carlos Peres of the UK’s University of East Anglia.

It turns out that even in these protected forests, as populations of larger mammal species like tapirs and monkeys decline due to hunting, the carbon content of the forest goes down.

Large mammal species play a vital role in dispersing large-seeded trees associated with high wood density, Peres, the lead author of the PNAS paper, said in a statement: “We show that dense-wooded, large-seeded Amazonian tree species are replaced by light-wooded trees that produce smaller seeds, which continue to be dispersed in overhunted forests by more resilient smaller mammal and bird species.”

Peres and co-authors estimate that over-hunting of large-bodied, fruit-eating mammal species in the Amazon — species key to spreading the seeds of large rainforest trees — leads to 2.5 to 5.8 percent losses in above-ground biomass on average. Some areas could see losses as high as 26.5 to 37.8 percent, they said.

Taal Levi of Oregon State University in the United States, an author of the study, said that properly managing wildlife could have big benefits for the climate.

While 2.5 to 5.8 percent carbon losses on average may sound negligible, it adds up to a serious chunk of greenhouse gas we risk sending into the atmosphere, Levi said: “The loss of forest biomass may not sound like a lot but in an area as vast as the Amazon, the impact could be huge — a projected 313 billion kilograms of carbon not being absorbed.”

The team of researchers, which also included scientists from the National Institute of Amazonian Research and Fiocruz Amazônia, both in Brazil, looked at a standardized network of wildlife surveys across 166 Amazonian hunted and non-hunted forests to determine the extent to which these mammalian frugivores have been destroyed by hunters.

The team then analyzed data from 2,345 one-hectare forest plots in the Brazilian Amazon containing some 129,720 large trees. They say that simulations based on that data showed widespread erosion of forest carbon stocks.

Between 77 and 88 percent of forests lose above-ground biomass as they continue to be over-hunted, the team found. They add that the world’s carbon market stand to lose anywhere from $5.9 trillion to $13.7 trillion-worth of carbon credits.

The University of East Anglia’s Peres said that the UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program, formally included in the Paris climate agreement last December, defines tropical forest degradation entirely in terms of more evident forms of human disturbance, such as logging and forest fires.

“Yet even apparently intact but otherwise defaunated forests should be considered as degraded because the insidious carbon erosion processes we highlight in this paper are already well underway,” Peres added.

“Even protected areas do not necessarily ensure the protection of large vertebrates in most remaining tropical forests. Either we stand up and effectively protect these wildlife populations, or overhunting will erode their populations until we see major losses in both forest biodiversity and forest ecosystem services.”

CITATION

- Peres, C.A., Emilio, T., Schietti, J., Desmoulière, S.J.M., & Taal Levi, T. (2016). Dispersal limitation induces long-term biomass collapse in overhunted Amazonian forests. PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516525113