- A new study has identified some of acoustic sanctuaries off the coast of British Columbia in the hope that they may be protected.

- Researchers emphasize that these opportunity sites can be protected with little change to current shipping patterns, which makes them a relatively easy target for conservation.

- Seizing the opportunity to protect acoustic sanctuaries now, is invaluable to the longevity of protected marine mammals.

Imagine living in an environment of constant noise where you cannot get anything accomplished. Ocean noise pollution caused by shipping, oil and gas development, and other human activities is making this the reality for marine mammals in many places, interfering with their ability to detect prey and communicate with one another. Yet some areas of the ocean remain refuges of quiet. A new study has identified some of these acoustic sanctuaries off the coast of British Columbia in the hope that they may be protected.

The study, which was published in Marine Pollution Bulletin, identifies these quiet spaces as “opportunity sites.”

“They represent places where we could protect animals simply by maintaining the status quo,” Rob Williams, lead author of the study, told Mongabay. Williams, a marine conservation biologist, is co-founder of the research nonprofit Oceans Initiative, which is based in Seattle and Alert Bay, British Columbia.

One challenge to identifying and preserving these environments is that marine mammals differ in where they live and in their sensitivity to noise. “[E]ach species has different distribution and habitat preferences within a country’s territorial waters, and different species with different hearing anatomy will hear the same sound differently. What is noisy to one species may seem quiet to another,” Williams said in an email.

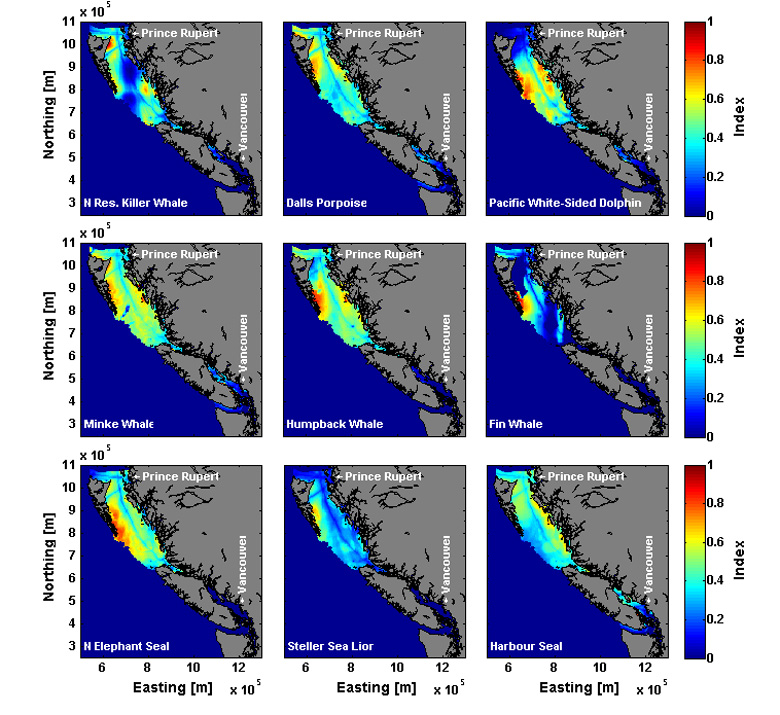

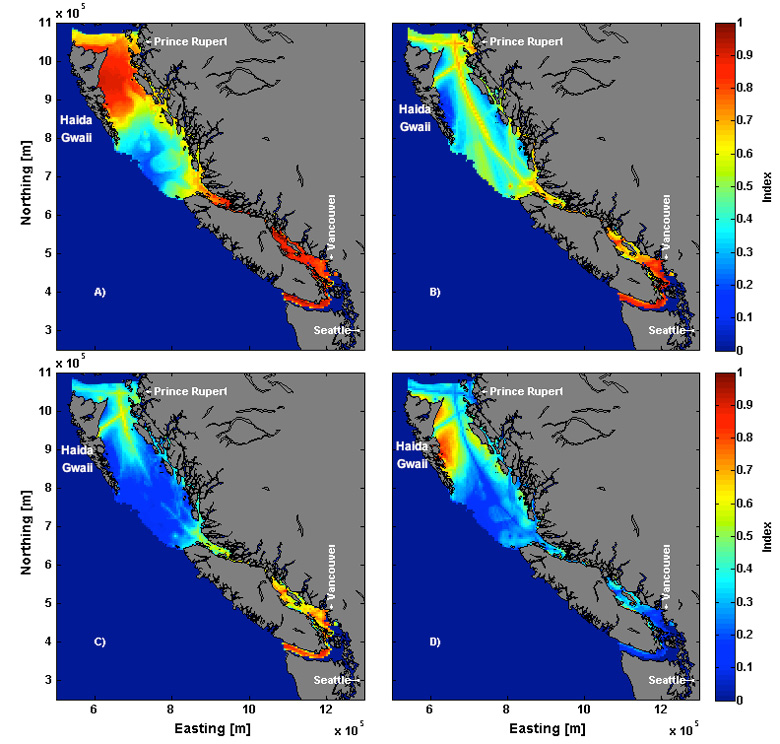

For the study, he and his co-authors developed detailed maps showing how risk from noise varies across the region for 10 marine mammal species living there. To do this, they drew on existing research describing ship traffic patterns to predict ambient noise levels, as well as literature on the distribution and hearing sensitivity of the 10 species.

Maps from the study show the Pacific coast just north of Vancouver displaying quiet zones for fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus), minke whales (B. acutorostrata), humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), killer whales (Orcinus orca), Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens), harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena), Dall’s porpoises (Phocenoides dalli), Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus), northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris), and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina).

The authors emphasize that these opportunity sites can be protected with little change to current shipping patterns, which makes them a relatively easy target for conservation. “We do not intend to minimize the amount of work that it will take to make noisy areas quieter. But one of the lessons learned from other pollution-prevention exercises is that it pays to start with so-called ‘low-hanging fruit’,” the authors write.

Williams further suggested that shipping companies could use the maps to direct their ships to slow down when approaching areas where animals that are sensitive to noise live. Not only would this reduce noise, but it would also help curb the risk of a ship striking a whale or other marine mammal, he noted.

Williams also said managers could use the map data to identify the species most threatened by existing noise levels and work to protect them first.

In a previous study, Williams and his team took the opposite approach, identifying problem areas where noise pollution had become particularly severe. In the present study, the team takes pains to point out that preserving quiet refuges should not come at the cost of neglecting to quiet these noisy areas. “On the contrary, habitat restoration is a central task in conservation biology. It is just that it is exceedingly difficult to reduce input of anthropogenic noise from sources outside a protected area,” the authors write.

Difficult though it may be to quiet areas marred by noise, Williams said there are strategic ways to make progress. For instance, he said that to reduce ship noise, a major component of ocean noise, it would be easier to build new, quieter ships than to try to make existing ships quieter. “Shipping companies already have to replace ships as their fleet ages. If countries decide to reduce noise levels in their coastal waters, they could offer financial incentives to encourage companies to do a noise audit of individual ships in their fleet, and replace the noisiest ships with quieter ones,” he said.

As for the sanctuaries of quiet the new study identifies, Williams and his co-authors believe that seizing the opportunity to protect them now is invaluable to the longevity of protected marine mammals. “[I]f we fail to identify pockets where important wildlife habitats are still quiet and also manage human activities in order to keep them that way, we can expect those acoustic sanctuaries or refugia to disappear eventually,” Williams said.

The song of a humpback whale (4.2MB mp3 file)

An underwater recording (0.3MB mp3 file)

Citations

- Erbe, C., Williams, R., Sandilands, D., Ashe, E. (2014). Identifying Modeled Ship Noise Hotspots for Marine Mammals of Canada’s Pacific Region. PLoS ONE 9(3): e89820.

- Williams, R., Erbe, C., Ashe, E., Clarke, C.W. (2015). Quiet(er) marine protected areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 100(1): 154-161.