- Unregulated gold mining expansion spurred by an insatiable international demand is quickening its pace up rivers and through once-primary rainforest in southwestern Peru’s Madre de Dios Department.

- A recent analysis of satellite imagery indicates mining has spread quickly up the Upper Malinowski River, displacing 329 hectares over the course of a year.

- In addition to deforestation, gold mining is releasing mercury into the air and waterways, putting downstream communities at risk of contamination.

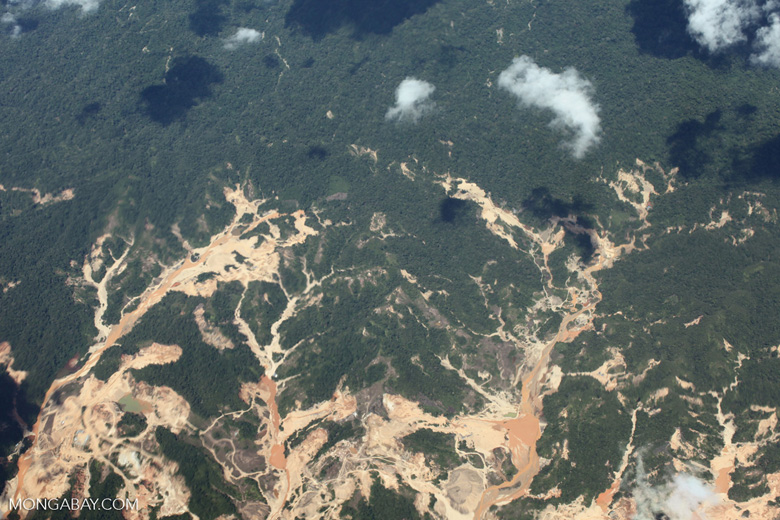

In the middle of some of the most spectacularly diverse rainforest in Peru, contiguous with the larger Amazon basin, a crisis is unfolding on a scale that remains unchecked despite efforts by a harried government to impose regulations. Gold mining is taking over the region, and expanding into once-pristine forest. In May this year, scientists from the Amazon Conservation Association (ACA) documented over 850 hectares (8.5 square kilometers) of gold-mining related deforestation in the Upper Malinowski River in the Madre de Dios Department of Peru. Six months later, they have now verified that that deforestation has been expedited.

According to the World Gold Council and its report on Gold Demand Trends for the Third Quarter of 2015, there were 183,600 metric tons of gold in existence above ground at the end of 2014. Central and South America produce around 17 percent of the total newly-mined gold each year.

U.S. gold prices fell to a five-year low in July this year, bouncing back in August. Watchful consumers responded to the new lower prices by consuming more gold: demand climbed 8 percent and jewelry demand grew 6 percent in the third quarter of 2015. In fact, U.S. gold Eagle coin sales rose to levels unmatched since the financial crisis.

“Gold as a reserve asset remains firmly on the radar,” concludes the report, as central bank purchases this quarter almost matched third-quarter levels of 2014.

While the World Gold Council maintains it is committed to procuring gold through responsible and sustainable means, the reality in many mining areas is quite the opposite.

In the Madre de Dios Department of Peru, artisanal and small-scale gold-mining forms the bulk of the industry, with people from surrounding areas moving into makeshift yet sprawling communities to cash in on the world’s never ending demand for gold. Here, mining is not a question of hard hats and bulldozers, but clunky generator-fed operations that use mercury to amalgamate the fine gold dust found in Amazonian soils. There are no safety precautions because most of this mining is still highly illegal.

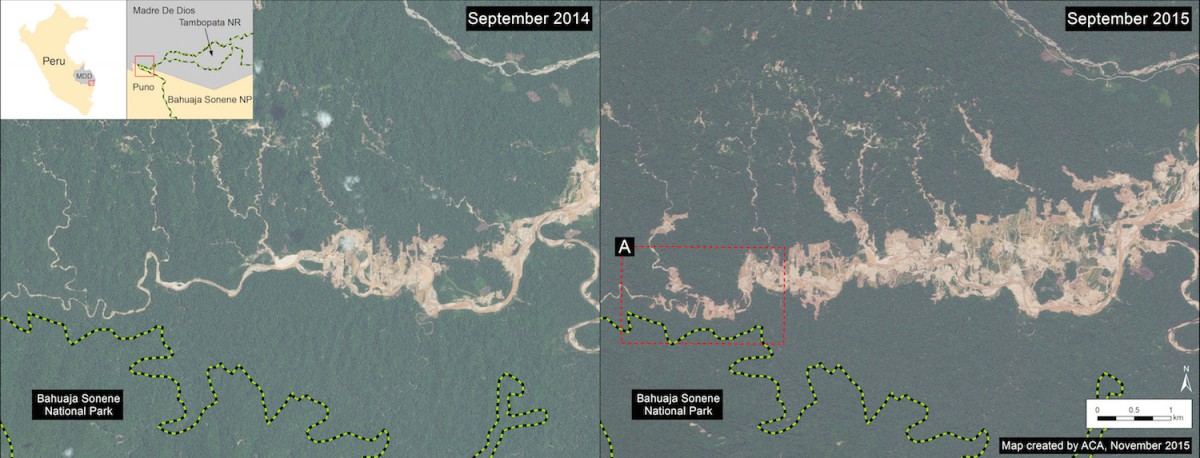

Using satellite imagery and a staff that constantly monitors areas of disturbance, the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) run by Matt Finer and Sidney Novoa of the Amazon Conservation Association compares imagery over time for about 30 locations in the Amazon basin.

One such comparison of two high-resolution images taken a year apart (September of 2014 and 2015) along the Upper Malinowski River shows that deforestation expanded by 329 hectares over the year. The deforestation is clearly linked to gold mining and has not only spread upstream rapidly, but is now abutting the border of Bahuaja Sonene National Park.

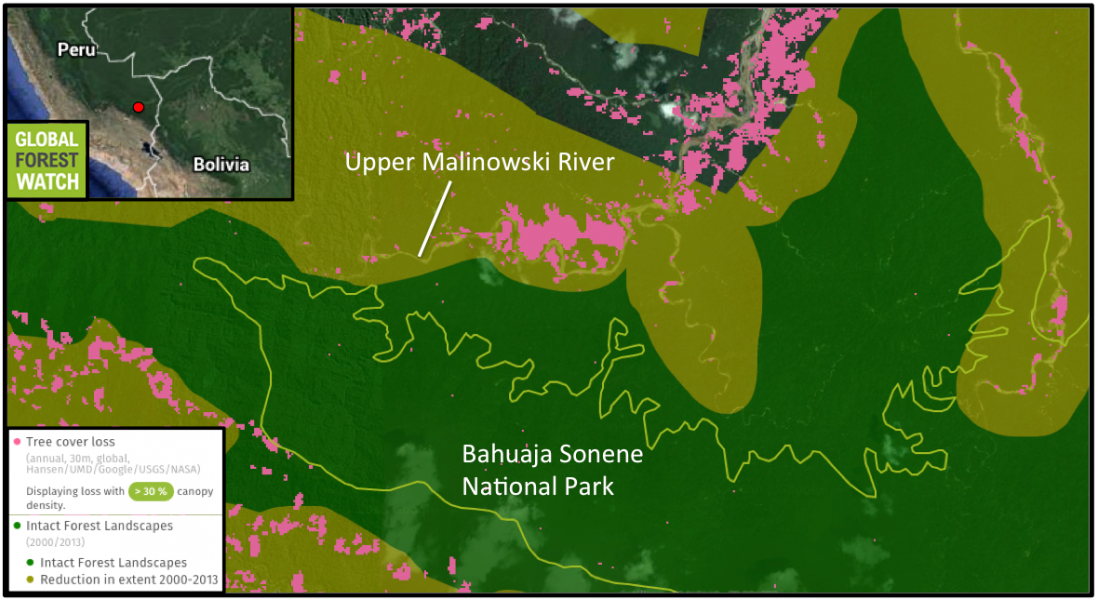

Finer and Novoa conclude that there appear to be two main gold mining deforestation fronts in the Madre de Dios. The first is La Pampa, just east of Upper Malinowski, located within the buffer zone of the Tambopata National Reserve. The second front on the Upper Malinowski is now shown to be within the buffer zone of the Bahuaja Sonene National Park.

The forest monitoring platform Global Forest Watch (GFW) shows this deforestation is happening in areas that were covered in large areas of primary forest called Intact Forest Landscapes (IFLs) as recently as 2000. In total, the region comprising the recently detected mining expansion lost 648 hectares of IFL cover from 2001 through 2014. Of that, 280 hectares – almost half – was lost in 2014 alone, indicating a sharp upward trend in recent deforestation.

Both parks are home to some of the Amazon’s most charismatic creatures – from the endangered Baird’s tapir (Tapirus terrestris) to the squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis). But all of these animals are now threatened by habitat loss due to deforestation as well as habitat contamination by mercury. These effects also extend to local human populations. According to the ACA’s Fact Sheet on illegal mining, nine of the fifteen most-consumed fish in local markets have mercury levels that are higher than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended limits.

Recent governmental efforts to control illegal mining have resulted in severe protests in the region. Given that most of the population of Peru resides west of the Andes, along with the bulk of the judicial infrastructure, it has been particularly difficult for the government to effectively control illegal mining in areas that are yet undeveloped, such as the eastern Madre de Dios. Supreme Decree 013-2015 proposed to circumvent those difficulties by controlling the sale of chemical compounds that are used for illegal mining purposes, including gasoline, but this affects the lives of everyone in the region and not just those participating in mining. Conflict resolution is ongoing in the region.

Citation

- Finer M, Snelgrove C (2015) Gold Mining Deforestation Rapidly Advancing along Upper Malinowski River (Madre de Dios, Peru). MAAP: 19.