- The black-footed ferret is one of North America’s most endangered mammals, due to the decimation of its prey species, the prairie dog.

- Researchers need to determine which prairie dog colony complexes are suitable for reintroduction of the endangered black-footed ferret.

- World Wildlife Fund and partners are using Unmanned Aerial Systems (drones) to assess prairie dog habitat in Montana’s Fort Belknap Reservation.

- If drones provide an accurate assessment of prairie dog habitat for black-footed ferret restoration, they could be implemented in similar habitat conservation efforts elsewhere.

How can species reintroduction projects ensure success? One way is to accurately monitor the target species and their habitat.

A team working to bring back the endangered black-footed ferret to the plains of western North America is deploying unmanned aircraft systems (UASs, UAVs or drones) to strengthen monitoring of the species’ habitat.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) partnered with Behron and Associates, Idaho State University, the Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department, Topcon, Eagle Digital Imaging and ESRI to deploy UASs to monitor black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) habitat. Kristy Bly, senior wildlife conservation biologist at WWF’s Northern Great Plains Program, explained to Wildtech that the team is assessing whether drones can be used to effectively monitor black-footed ferret habitat in a study area on the plains of the 675,147-acre (273,222 ha) Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana. In early 2013, WWF and the Fort Belknap Fish and Wildlife Department reintroduced the ferrets to the Ft. Belknap prairie dog colony complex that they had occupied years before. (A complex is a group of prairie dog colonies grouped together within a mile of one another.)

The decimation of the prairie dog

Only around 300 black-footed ferrets still live in the wild; the species is listed as Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. The ferrets rely on prairie dog (Cynomys spp.) burrows for shelter and are obligate predators of prairie dogs — they depend primarily on prairie dogs for food.

But large-scale prairie dog eradication programs conducted throughout the 1900s and an exotic disease (sylvatic plague) that decimated — and still affects — prairie dog populations have made the ferrets one of North America’s most endangered mammals. The U.S. government originally authorized prairie dog eradication programs to appease farmers and ranchers who believed that the colonies substantially decreased the area of forage available for cattle. And eradication continued into the 1990s, despite evidence that cattle actually prefer and benefit from the nutrient-rich grasses found in prairie dog habitat. Adding insult to injury, sylvatic plague — a disease introduced into North America in the early 1900s — is highly lethal to ferrets and their prairie dog prey.

As a keystone species, prairie dogs support the Northern Great Plains ecosystem. Their grazing and burrowing behaviors improve soil quality by increasing the amount of water retained in the soil, modifying vegetation height and species, increasing the uptake of nitrogen by plants and facilitating soil mixing. These processes result in prairie dog colony habitat being preferred by ungulates such as cattle, bison and pronghorn for grazing (Kotliar et al. 1999).

Black-footed ferrets rely on prairie dog colonies for food and habitat, so the smaller and farther apart colonies are, the less successful ferret dispersal between them becomes. Because the ferrets are territorial, large prairie dog colony complexes are required to support a self-sustaining population. For example, 30,000 acres of prairie dog colonies once hosted a mere 300 ferrets.

Limits of classic prairie dog research methods

For a reintroduction project to qualify for an allocation of ferrets from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the site must have enough habitat to support the predators. And once the ferrets are reintroduced, the Fish and Wildlife Service requires annual monitoring of their numbers and habitat, including “the minimum number of black-footed ferrets alive each fall, the size of the prairie dog complex and prairie dog density,” according to Bly.

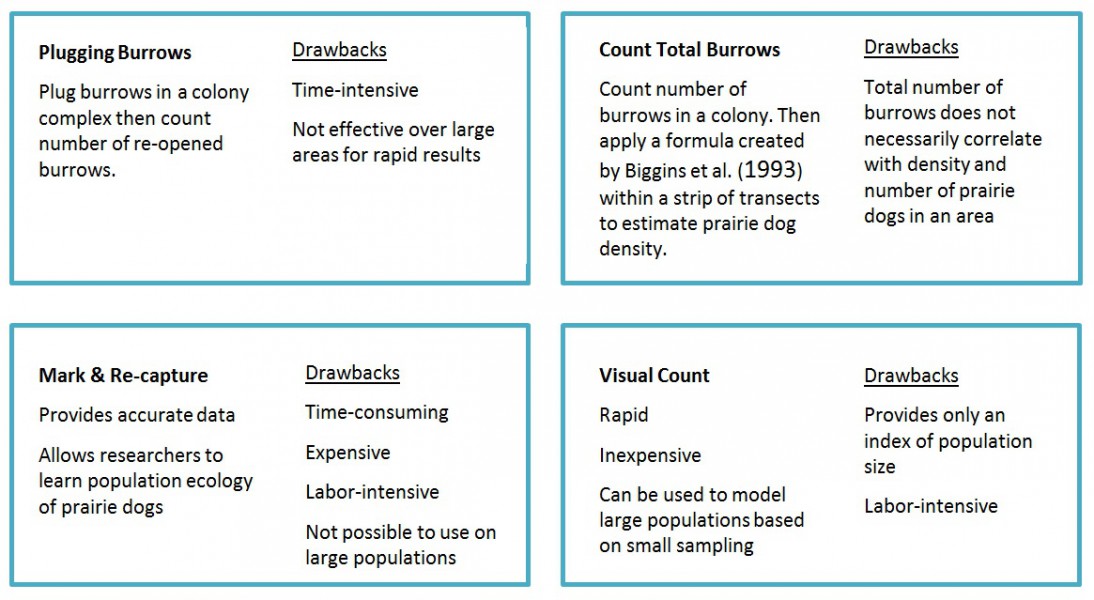

To measure these complexes and calculate burrow density, researchers must traverse the perimeters of prairie dog colonies, record the route using GPS and count burrows. These methods require many hours of labor and have multiple drawbacks, detailed in the diagram above. And tribal lands often lack the resources, scientists and funding to accomplish these tasks.

The Black-footed Ferret and UAS Project

The UAS project originated from a desire to improve monitoring of the expansive ferret habitat in the Fort Belknap study area.

In an email to Wildtech, Bly explained that the two primary goals of the project are to “(1) test and document the efficiency and accuracy of monitoring prairie dog populations (e.g., BFF habitat) on the Fort Belknap Reservation using new technology, and (2) determine the feasibility of using UAS acquired imagery combined with GIS as a data collection tool.”

The project team began using UASs in an attempt to rapidly and effectively map prairie dog colony complexes and assess prairie dog density within the ferret recovery area on the Fort Belknap Reservation. Flying at speeds up to 50 mph, the Topcon MAVinci Sirius Pro UAS follows a pre-programmed flight plan set by the MAVinci Desktop Software. The UAS carries a 16-megapixel near-infrared camera capable of capturing images with green, red and infrared spectral bands. The camera is triggered by the UAS to take photos at specified GPS locations, which are three dimensional points that include latitude, longitude, and elevation, rather than time-intervals. Otherwise, the area’s heavy winds, which affect flight speed, could cause uneven data collection.

Once the team completed 11 acquisition flights, they compiled 5,500 images of the prairie dog habitat taken from the UAS into an orthomosaic, or a georeferenced photomap. Currently, the team is using image-processing and GIS software to identify and count prairie dog burrows in the images in order to estimate the colonies’ size and burrow density. The next step, Bly says, is to compare the computer-generated estimates of burrow density and colony size with estimates obtained by both traditional field collection methods and manual estimates obtained from the imagery.

Soaring into future research with drones

Bly and colleagues have high hopes for the implementation of UAS in advancing black-footed ferret recovery. If the UAS succeeds as a data collection tool, they plan to replicate the prairie dog mapping and density work at other ferret reintroduction sites.

In the future, the team wants to use UAS and real-time thermal imagery to directly quantify ferret populations on the Fort Belknap Reservation. Black-footed ferrets are nocturnal, so thermal images might help researchers estimate the minimum number of individual ferrets within the reintroduction area.

To ensure success of the black-footed ferret reintroduction at Fort Belknap, sylvatic plague must be mitigated in both prairie dog and ferret populations. Protecting prairie dogs from the “lethal impacts of the non-native disease sylvatic plague is the primary way we ensure habitat quality for black-footed ferrets,” Bly said. An oral vaccine for plague was recently developed for prairie dogs and is now being tested in the field. The team hopes to develop methods for deploying UAS to deliver the oral sylvatic plague vaccine for prairie dogs at ferret reintroduction sites.

In addition to helping conserve an endangered carnivore, Bly adds that “this project was unique in that many partners from varying backgrounds united to test a new technology evaluating habitat for an endangered species on tribal lands. In addition, this project has been a great opportunity for college students to learn cutting edge technology/UAS skills. We think both aspects are very exciting!”

If you’ve used UASs to monitor habitat availability for species of concern, let us know in the forum. This and other new projects will benefit from your experience.

Citations

Bevers, Michael, John Hof, Daniel W. Uresk, and Gregory L. Schenbeck. “Spatial Optimization of Prairie Dog Colonies for Black-Footed Ferret Recovery.” Operations Research 45.4 (1997): 495-507. Web. <http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_1997_bevers_m001.pdf>.

Miller, Brian, Gerardo Ceballos, and Richard Reading. “The Prairie Dog and Biotic Diversity.” Conservation Biology 8.3 (1994): n. pag. Web. <http://www.ecologia.unam.mx/laboratorios/eycfs/faunos/art/Gce/AA39.pdf>.

“Top Down” Wildlife Conservation.” Topcon Positioning Systems, Inc.N.p., 30 July 2015. Web. 16 Sept. 2015. <https://www.topconpositioning.com/insights/%E2%80%9Ctop-down%E2%80%9D-wildlife-conservation>.

World Wildlife Fund. “Prairie Dogs, Black-Footed Ferrets, and a Pilot-less Plane.” Oximity. N.p., n.d. Web. <https://www.oximity.com/article/Prairie-Dogs-Black-Footed-Ferrets-and-1>.