- As Indonesia burns, companies, smallholders and the government have all been assailed as responsible parties.

- A lack of reliable data, though, has kept researchers from drawing more specific conclusions as to the precise causes of the fires.

- One think-tank is using satellite imagery and ground checks to create a comprehensive map of Indonesia’s plantations in the absence of publicly available concession data.

As fires burn across Indonesia as badly as since the disaster of 1997, blanketing parts of the country and its neighbors in a noxious haze, a variety of assertions have been made as to precisely who and what are responsible for the flames, widely used as a tool for clearing land.

Some point the finger at “smallholders,” itself a vague term used to reference a vast ecosystem of landowners ranging from the poor and tiny to the medium-sized, the latter of which can command significant capital.

Others direct their ire at plantation firms. Under Indonesian law, companies bear responsibility for fires that break out in their concessions, whether they started them or not. President Joko Widodo has called for delinquent firms to have their permits revoked, and seven executives were arrested in Riau last week, either for setting fires illegally or for failing to prevent them.

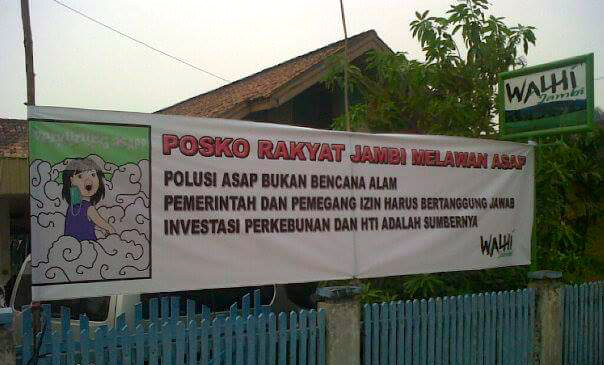

Meanwhile, the Indonesia Forum for the Environment (Walhi), an NGO, has set up complaints posts for people who want to join in on a class action suit against the government, seen as negligent or even complicit in allowing this dry season’s burning to reach such epic proportions.

“The government has committed [a] fundamental human rights abuse because it does not stop [the fires] from happening,” said Raichatul, commissioner of the National Human Rights Commission, as quoted by kompas.com on Saturday.

The situation has become a crisis. Smog is blowing across the strait into Singapore and Malaysia, causing an international outcry. But the situation is far worse in Sumatra and Kalimantan, where the air has become hazardous to breathe.

In Riau, a mass exodus has seen thousands leave the province to escape the scourge. In the capital of neighboring Jambi province alone, tens of thousands of people have reported acute respiratory infections.

In an interview with Mongabay, one Jambi resident described waking up to a house full of white and black ash every morning. She’d mop the floors, but the refuse kept appearing, even though the windows were shut tight.

“It turned out it was coming in through a small vent,” said Santi, 30, adding that her daily water expenses have gone through the roof.

For a month, Rinaldi, another Jambi resident, has kept himself and his family locked inside their home. The 36-year-old has two small children, whom he won’t let out to school, and a pregnant wife, and he doesn’t want to take any chances. They have already developed a cough.

“Don’t breathe too deeply,” he warned. “You’ll feel it right in the chest.”

Harder than it might seem

Amid the finger-pointing, some are taking a wider view.

Andika Putraditama, research analyst at the World Resources Institute, a Washington D.C.-based think-tank which created the Global Forest Watch platform, feels the media has tended toward an oversimplified narrative of blame.

For example, he said, in mining a series of graphics the WRI recently posted to its website, one newspaper focused on a list of the concessions with the most hotspots but didn’t mention an accompanying chart showing that most fires are burning outside company land.

“They just took a graphic that blamed an [Asia Pulp and Paper supplier], but it lacked context,” Andika said.

Context can be hard to come by. These days, most fires can be spotted by satellite, but because of a lack of data on where plantations in Indonesia lie and who operates them, determining a fire’s origin can be a tall order.

It starts with concession maps, many of which are hidden from public view.

Several years ago, the Forestry Ministry (since merged with the Environment Ministry) released some form of maps for logging and pulp-and-paper concessions, but these are not as up to date as Andika says researchers need to draw stronger conclusions.

The whereabouts of oil palm concessions are even harder to identify. The ministry has released a smattering of maps it has gathered from across the levels of government, but it lacks the full array; permits for oil palm come from local administrations, the Agriculture Ministry and the Agrarian and Spatial Planning Ministry.

A chunk of maps has come out through the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, a voluntary initiative that requires member companies to meet certain transparency standards, but not everyone has fulfilled their obligations.

“The spotlight has been on the Forestry Ministry, but the focus should also be on the Agriculture Ministry and the Agrarian Ministry,” Andika said.

To fill in the gaps, the WRI has contracted a Russian NGO, Transparent World, to map plantations using satellite imagery and ground checks. While still incomplete, the data is enabling the WRI to begin to divide the fires into four typologies, spanning those that occur in planted and non-planted areas, within and outside concessions.

Combined with other information, such as imagery from satellites that show how a fire is moving, these distinctions can shed light on what sort of actor is likely to have started a fire.

The satellites only reveal so much. But ground checks present their own obstacles, said Jacob Phelps, an environmental scientist who was affiliated with the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Indonesia until last month.

As part of a project looking into the fires’ underlying causes, Phelps and his colleagues identified nine of the biggest blazes and tried to figure out what types of actors might have been behind them.

In many parts of the world, farmers live near their fields, so the researchers started by searching for residents within three kilometers of the hotspots. But they often found the area uninhabited. So they expanded their radius to seven kilometers. Still nothing.

“There was no one on the road either because [unlike other crops] you don’t have to tend oil palm everyday,” Phelps said. “The point is, the idea that we can go out and have really reliable fire attribution is – well, it’s not an easy process.”

Afdhal Mahyuddin, a Riau-based researcher for WWF-Indonesia who monitors fires through hotspot analysis and ground checking as part of the Eyes on the Forest program, said companies as well as smallholders have strong incentives to burn.

“Companies need to save costs for improving pH balance of peatlands, getting plantation fertilizer cheaply, avoiding excavators use, so burning is a very good option,” Afdhal said. “And don’t ignore that for many years, rumor that companies can get easy money from insurance of their land. This also needs to be investigated.”

Encroachment is often related to organized crime and backed by significant capital, he added.

“They target abandoned concessions, conservation areas, disputed land, so they get the benefit of the doubt. So it is complex. But I believe that companies starting fires are highly responsible because the burned areas are the same over many years. … The economic motive cannot be ignored.”

On a general level, said Peter Holmgren, CIFOR’s director-general, it’s clear the actors behind the fires come from different segments of society. They are large and small, on-site and off-site. Sometimes the authorities are involved.

Getting more specific is tricky. “Figuring out what one particular hotspot actually indicates, what the activities on the ground have been and are, who are doing it on the ground, who is carrying out the investment behind that land conversion, and why aren’t the authorities more active in dealing with that particular fire, is a very tedious investigation,” Holmgren said.

Unless there is a serious attempt at prosecution and possibly also propaganda to deal with these underlying investment drives, as well as an effort to strengthen spatial planning and improve management of peatlands, which are like a tinderbox when drained to plant crops like oil palm, he added, the fires will likely continue to recur.

A previous version of this article described the Russian organization contracted by the WRI as a firm. It is an NGO.

CITATIONS:

Jogi Sirait. “Selain Ganggu Aktivitas, Asap di Kota Jambi Telah Sebabkan 20.000 Warga Terjangkit ISPA.” Mongabay-Indonesia. 15 September 2015.

Andi Fachrizal dan Sapariah Saturi. “Mau Gugat Pemerintah soal Asap? Berikut Ini Posko-posko Pengaduan Warga.” Mongabay-Indonesia. 16 September 2015.