- Beehive fences, a technology developed by Dr. Lucy King, is now in use in Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya and Sri Lanka and being investigated in India and Malawi.

- Researchers are leveraging the bee-elephant dynamic to find new ways to protect economically valuable trees and crops.

- Robin Cook, a student at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa is testing suspending beehives in marula trees as elephant deterrents.

This is a story about elephants, bees, trees, and a drink called Amarula.

Amarula Cream is a liqueur distilled from the fermented fruit of the marula tree. The trees’ fruit is beloved by humans and animals alike — elephants and other animals feast on its sweet flesh, and humans use the fruit to make beer, oil, medicine and — of course — Amarula Cream.

But now, elephants and humans are butting heads over the marula tree. In protected areas in South Africa, tourists and land managers worry that the concentration of the country’s elephant population into these limited areas could wreak havoc on the ecosystem’s iconic tree species. Swaddling a tree’s trunk in wire mesh can help it withstand an elephant’s attention, but now researchers are testing out an alternative technique, one with potential for a few sweet rewards beyond protecting trees.

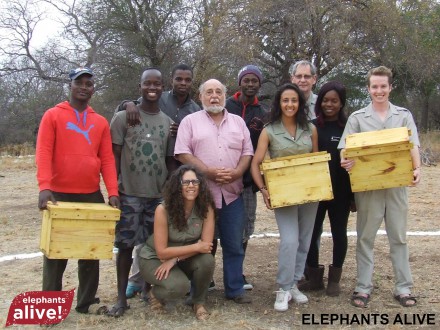

Back in 2002, Fritz Vollrath and Iain Douglas-Hamilton from Save the Elephants (STE) realized that elephants avoid trees with beehives living in them. That observation led researcher Lucy King to develop a novel technique to prevent elephants from raiding crops: fences with beehives suspended from the wires. Elephants Alive Program Manager Michelle Henley was inspired by Lucy’s work and asked Robin Cook, a student at the University of the Witwatersrand, if he would be interested in exploring whether hives could protect trees more effectively than wire nets.

Working in the Jejane Private Nature Reserve near Kruger National Park in South Africa, Robin and his team have established a baseline measure of elephant impact on 150 marula trees and built 115 beehives. Now they’ll hang two hives apiece on half of the trees and monitor them for a year to see if the bees keep the elephants at bay.

Elephants Alive, for whom Robin is conducting the research, has partnered with the mostly-female anti-poaching unit known as the Black Mambas for the project. Members of the Black Mambas will accompany Robin on weekly trips to monitor the marula trees and the hives. The Black Mambas, in turn, will help disseminate beekeeping skills in their own communities.

Expanding the HEC toolkit

Tension over iconic trees represents a relatively mild form of human-elephant conflict (HEC). But across Asia and Africa, development and expanding agriculture are restricting elephants’ ranges, and remaining protected areas are often too small and fragmented to support a species that maintains home ranges up to 772 square miles (~200,000 ha). Expanding human presence in traditional elephant travel routes regularly puts elephants in contact with rural communities. The resulting HEC can put humans and elephants at risk of injury or death and often results in crop and property damage.

A combination of conflict-mitigation strategies could reduce HEC (Hoare 2012). Such tactics range from cheap, low-tech defenses such as shining torches, banging drums and building chili fences, to expensive, high-tech options, such as electric fences and drones. Because elephants are highly intelligent animals and become habituated to deterrents, rural communities must continue adopting new methods to protect their properties (O’Connell-Rodwell et al. 2000). Effective, cheap, sustainable and less labor-intensive methods could encourage broader adoption.

Honeybee fences, the idea that inspired Robin Cook’s marula tree experiment — are being deployed by farmers in Botswana, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya to dissuade elephants.

On the fence

Working with STE, a group of farmers in Kenya were the first to build African honeybee fences in an effort to prevent crop raids and property destruction. Farmers suspend beehives from a fence about every 10m along the frontline between a likely elephant path and their farms. Although honeybees are generally less active at night, when most crop raids occur, pressure on the wire fences disturbs the bees, which in turn deter the elephants — the areas around an elephant’s eyes, behind the ears and on the tip of the trunk are particularly sensitive to stings (King 2013).

Although honeybee fences use basic technology, they still represent a substantial investment for subsistence farmers and require regular maintenance. In Kenya, for example, 240m of beehive fence (enough to protect one acre of farmland) costs approximately $800. Farmers must shelter hives from rain and direct sun, protect their hives from the greedy paws of the honey badger and other predators and ensure that the fence posts and wires are secure.

But participating farmers see the fences as a win-win: “I have acquired money from honey, educated my children, got medicines from honey as well as improved on my family welfare because elephants no longer invade my gardens,” Agnes Ndyomubandi, a 56-year-old Ugandan farmer, told the Daily Monitor. The threat of real bees seems to help deter elephants, and as an added bonus, the hives produce honey, wax and propolis (a medicinal resin collected by bees) (King 2012). Although bee fences require purchasing and maintaining the hives and fence materials, farmers can recoup some costs through the sale of bee products.

During two years of field trials in northern Kenya, researchers compared the effectiveness of bee fences to traditional barriers made of thorn bushes. Of the 45 successful farm invasions during that period, only one elephant entered a farm through a beehive fence. The technique is more likely to succeed at lower elevations, with individually owned hives, and when the fences fully enclose each farm, according to the STE beehive fence construction manual.

Nonetheless, Richard Hoare, an expert on the causes and mitigation of HEC, emphasizes that beehive fences are “simply one potential addition to the wide and disparate ‘toolbox’ of measures that can be employed against problem elephants,” according to his recent paper “Lessons From 20 Years of Human–Elephant Conflict Mitigation in Africa.” Hoare notes, for example, that the technique is accepted only in communities with “cultural or historical exposure” to keeping bees.

Mikumi National Park, a case study

In 2012, Tanzanian wildlife consultant Alex Chang’a helped build beehive fences in four communities adjacent to Mikumi National Park, the nation’s fourth-largest park. “Beehive fences were able to prevent elephants from entering the farm,” Chang’a wrote in an email, adding that many empty hives were occupied within a short period and farmers were excited about the project.

But the region’s climate posed a challenge: After a single rainy season, the fence posts rotted and had to be replaced. Then, during the dry season when there were no crops, cattle entered the fields and disturbed the hives. In response, some farmers removed their hives from the fences and hung them from trees instead.

When his group compared chili and beehive fences, they found that “in terms of replication of the project and expansion of the project, we thought chili can be adapted in different places very easily, rapidly and at very low cost, given that chili can be grown by farmers themselves,” he wrote. But farmers who overcame the challenges of maintaining honeybee fences were able to prevent elephants from entering their fields and enjoy the rewards of keeping bees, Chang’a wrote.

Out of Africa

Now, researchers are testing the beehive fence concept in other areas where humans and elephants clash over resources. Lucy King, who developed the beehive fence project in Kenya, is working with the Sri Lankan Wildlife Conservation Society and the Uda Walawe Elephant Research Project to study Asian elephants’ responses to the less-aggressive Asiatic honeybees and have started pilot plots in select communities.

STE is also exploring the use of beehive fences in Malawi and India. In fact, the Indian Minister of the Environment, Prakash Javadekar, recently advised state governments to consider implementing bee fences in an effort to reduce HEC nationwide.

If honeybee fences can help diminish human-elephant conflict in new areas and Robin Cook’s study bears fruit, bees, elephants, trees and humans could move toward a more peaceable equilibrium — a possibility as sweet and intoxicating as a glass of Amarula with a large dollop of honey.

Do you have experience with HEC? Any ideas about low-tech solutions to elephant crop raiding? Share your insights on the wildtech forum.

Want to sponsor one of Robin’s hives? Check out their work here.

Learn more about where, when, and how bee fences help keep elephants out of croplands through the sources below and here.

Sources

Graham, M.D., I. Douglas-Hamilton, W.M. Adams, and P.C. 2009. The movement of African elephants in a human-dominated land-use mosaic. Animal Conservation 20: 445-455.

Graham, M.D., N. Gichoh, F. Kamau, G. Aike, B. Craig, I. Douglas-Hamilton, and W.M. Adams. 2009. The use of electrified fences to limit human elephant conflict: a case study of the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Laikipia District, Kenya. Working Paper 1. Laikipia Elephant Project. Nanyuki, Kenya.

Hoare, R. 2012. Lessons from 15 years of human-elephant conflict mitigation: management considerations involving biological, physical and governance issues in Africa. Pachyderm 51: 60-74.

King, L.E., I. Douglas-Hamilton, and F. Vollrath. 2011. Beehive fences as effective deterrents for crop-raiding elephants: field trials in northern Kenya. African Journal of Ecology 49: 431-439.

King, L.E. 2012. Beehive fence construction manual: A step by step guide to building a protective beehive fence to deter crop-raiding elephants from farm land. 2nd ed. The Elephants and Bees Project. Nairobi, Kenya.

King, L.E. 2013. Elephants and bees: Could honey bees be effective deterrents for Asia’s crop-raiding elephants? Sanctuary Asia: 61-65.

O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E., T. Rodwell, M. Rice, and L.A. Hart. 2000. Living with the modern conservation paradigm: can agricultural communities co-exist with elephants? A five-year case study in East Caprivi, Namibia. Biological Conservation 93: 381-391.