- Bushmeat trends in northern Tanzania show consumption is tied most strongly with its low cost and ready availability in the region.

- Illegal hunting, for meat or other animal products, is a particular concern in regions with large migratory species.

- Bushmeat and animal products are also frequently consumed by wealthy people and are considered to be symbols of status in certain communities.

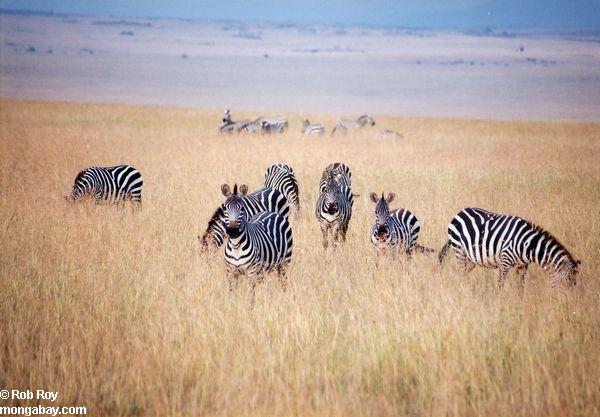

Hunting wild animals for food is not an uncommon practice across our world. From remote snow-covered forests in Alaska to the plains and jungles of Africa, animals are trapped so that people may eat. However, despite being an age-old practice, bushmeat hunting is potentially detrimental to wildlife. A study recently published in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science investigated bushmeat trends in northern Tanzania, finding consumption is tied most strongly with its low cost and ready availability in the region.

From 2013 to 2014, researchers surveyed 394 households in the Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem (TME) of Northern Tanzania in order to understand bushmeat consumption in this region. Overall, bushmeat here is generally regarded as an alternative food source that supplements the diets of people who can’t afford to purchase meat from domestic animals like goat, beef or chicken. But this may not always the case.

“Bushmeat and animal products are also frequently consumed by wealthy people and are considered to be symbols of status in certain communities,” the authors write.

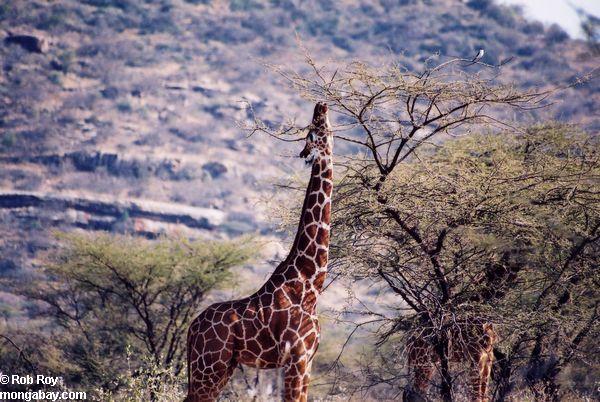

Illegal hunting – either for meat or other animal products – is leading to the demise of many animal species across Africa. And it is a topic that is of particular concern in regions with large migratory species, such as Tanzania. The authors contend that in order to effectively mitigate poaching, it’s important to understand the cultural, economic and social factors that might drive bushmeat as an industry.

Two such factors the researchers explored were ethnic differences and the effectiveness of law enforcement.

The Maasai is a prevalent ethnic group in the TME, one that is associated with sheep and cattle farming (pastoralists). Because of their agrarian way of life, bushmeat hunting is considered less prevalent amongst the Maasai. However, other groups in the region do not depend on farming as heavily. The researchers compared bushmeat hunting between the Maasai and non-Maasai. They hypothesized that the amount of bushmeat harvested by Maasai would be less compared to that harvested by non-Maasai communities, and also increase with ease of availability, decrease with prevalence of alternative proteins, and be more common amongst both comparatively poorer and richer households.

In addition, the researchers conducted household interviews before and after the Tanzanian government launched an intensive national campaign against poaching in the face of increased elephant poaching. Therefore, the researchers were able to assess the potential impact of this law enforcement effort on bushmeat hunting.

The researchers broke down their project by conducting house-to-house interviews in the TME region in various villages and subvillages. Each household visited was asked a variety of questions involving ethnicity, level of education, number of people in the household, if they owned cattle or sheep and bushmeat consumption. Specifically, they were asked whether or not they’ve eaten bushmeat, seen it for sale or participated in hunting for meat in the previous year. The researchers also took into consideration the distance of an interviewee’s household to Kigongoni, a major buhsmeat marketplace.

Overall the researchers reported that in 2013, 48 percent of respondents said that they noticed bushmeat available at local markets, and 38 percent admitted they’d consumed it. In 2014, those numbers dropped to 41 percent and 33 percent, respectively. However, the authors caution that it’s likely not all respondents were honest, and that bushmeat is consumed and made available at a higher rate than this study suggests.

As they expected, the researchers found that eating bushmeat is not an uncommon practice in the TME region and that its cheap price is potentially a key factor. However, they also got a few surprises.

“Maasai frequently admitted to bushmeat consumption and even hunting. This in stark contrast to Maasai in other parts of Northern Tanzania who had not reported consuming bushmeat at all,” the authors wrote. This difference is possibly due to a shift in lifestyle for the Maasai of the TME. A predicting factor for the Maasai of the TME is chiken ownership. The Maasai culture is not associated with raising chicken and other poultry. The deviation from a purely pastoralist lifestyle might indicate how other cultures influence the daily lives of the Maasai resulting in them raising poultry and eating and hunting bushmeat.

Despite having an abundant and readily available source of meat, the Maasai and other consumers still turned to bushmeat. Some respondents explained that hunting for bushmeat is mainly an opportunistic occurrence. And that hunting for a meal is typically limited to small mammals like the Kirk’s dik dik. However, it’s mostly young men living in villages with marketplaces that sell bushmeat such as Kigongoni and Mto wa Mbu, that hunt wildlife illegally. Similarly, it appears other factors normally attributed to influencing buhsmeat consumption don’t in the TME .”Between Maasai and non-Maasai ethnicities and between 2013 and 2014, household size, education level, cattle and shoat ownership had no significant impact on bushmeat consumption,” the authors write.

However, while some kinds of bushmeat are regarded as status symbols, the bottom line is that bushmeat is generally cheap – typically half the price of a domesticated animal. And this reality is posing a serious threat to conservation.

“Demand for cheap bushmeat is a serious threat to wildlife conservation in the ecosystem, and elsewhere in Tanzania,” the authors write, “and is often overlooked in the media and policy agendas.”