The Te Apiti wind farm in New Zealand was granted tradeable carbon offset credits when it was built in 2003/2004. Wind energy projects were popular in voluntary carbon markets in 2014. Photo credit: Jondaar_1.

The Te Apiti wind farm in New Zealand was granted tradeable carbon offset credits when it was built in 2003/2004. Wind energy projects were popular in voluntary carbon markets in 2014. Photo credit: Jondaar_1.

Nearly one billion carbon offset credits were voluntarily purchased over the past decade, which netted conservation and clean energy projects almost $4.5 billion, according to a recent report by the Washington D.C.-based conservation group Forest Trends.

Voluntary carbon markets provide corporations, governments, and anyone else looking to counterbalance their greenhouse-gas emissions the opportunity to buy offsets. One carbon offset credit represents one metric ton of carbon-dioxide emissions, or the equivalent in another greenhouse gas, saved through actions like preserving endangered rainforests, increasing energy efficiency, or installing clean-energy systems.

By contrast, in so-called "compliance markets," such as the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, carbon credits are bought to make government-mandated emissions reductions.

In 2014, carbon offsets equivalent to some 87 million metric tons of CO2 were purchased voluntarily, up 14 percent from the year before, the report states.

According to Forest Trend’s Kelley Hamrick, the lead author of the report, which is titled Ahead of the Curve: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2015, the nearly $4.5 billion spent on voluntary carbon credits over the past 10 years has had a much larger impact than the relatively small amount of money would suggest.

“Many of the rules and processes now commonplace in emerging compliance markets all over the world (valued at about $30 billion in 2014 alone, according to the World Bank) were tried and refined in the voluntary markets,” Hamrick told mongabay.com in an email.

In other words, governments seeking to create their own regulated carbon markets are doing so with far less risk because the voluntary markets have already tested offset projects and methodologies, Hamrick and her team found. They write in the report that the voluntary markets provide a “fertile testing ground for the concept of ‘payments for performance’ because private buyers typically only pay if emissions reductions are verified to a pre-determined standard.”

When carbon offsets first appeared, Hamrick told mongabay.com, there were criticisms about the verifiability of emissions reductions claims, especially regarding how it could be guaranteed that the emissions would have been created, or the forest in question would have been destroyed, without the additional investment. This led to third-party verification standards that now guide almost all carbon project development, she said.

For instance, many of the project methodologies and market frameworks informing the carbon pricing scheme established by California’s cap-and-trade program were first tested in voluntary markets, the report notes.

Methodologies for developing projects that avoid deforestation, distribute clean cookstoves in developing countries, and grow rice with a smaller carbon footprint were all “tested and honed by voluntary actors,” according to the report.

As further evidence of the outsize impact of the relatively small voluntary carbon markets, Hamrick said that the work funded by the voluntary purchase of carbon credits has had wide-ranging effects, such as allowing conservation activities that reduce deforestation to scale up from individual projects to regional and national programs.

Other kinds of projects can have a big impact even if they are done on a much smaller scale. “This work has also enabled small, on-the-ground offset projects, such as switching to cleaner-burning cookstoves, to utilize carbon finance in a way that made these projects financially viable,” Hamrick added.

Forest Trend’s Gloria Gonzalez, who contributed to the report, told mongabay.com in an email that in recent years, buyers have become more interested in projects with additional benefits beyond slowing climate change. These are also known as co-benefits, things like improving health and empowering women in developing countries.

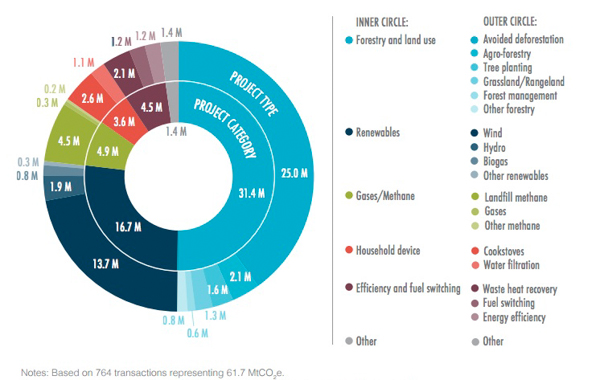

Transacted volume of carbon offsets in 2014 by project category and type, in metric tons of CO2 equivalent. Source: Forest Trends. State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2015. Click to enlarge.

The report tracks nearly 20 different types of projects, including forestry and land use, renewable energy, efficiency, and household device projects, such as cookstoves and water filtration systems.

“Out of the top seven project types tracked over the last decade, three are forestry-related (avoided deforestation, tree planting, and forest management) as these projects are highly valued for their social, health and other environmental benefits,” Gonzalez said. “Another project type, clean cookstove distribution, transacted the sixth-highest volume of all project types, even though we only started tracking it as a separate category in 2012.”

Offsets from forestry and land-use projects accounted for more than half of all voluntary transactions in 2014, led by avoided deforestation projects that saved the equivalent of 25 million metric tons of CO2 from being released. Renewable energy projects were also popular last year — wind offsets accounted for 13.7 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent.

Carbon credits may be part of the solution but they are no panacea. One billion metric tons of CO2 emissions may have been avoided through the purchase of offset credits over the past decade, but the world was projected to release roughly 40 times that amount — 40 billion metric tons — in 2014 alone.

Citations:

- Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace. Ahead of the curve: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2015. (2015).

}}