Liz Kimbrough with co-research by Anjali Kumar

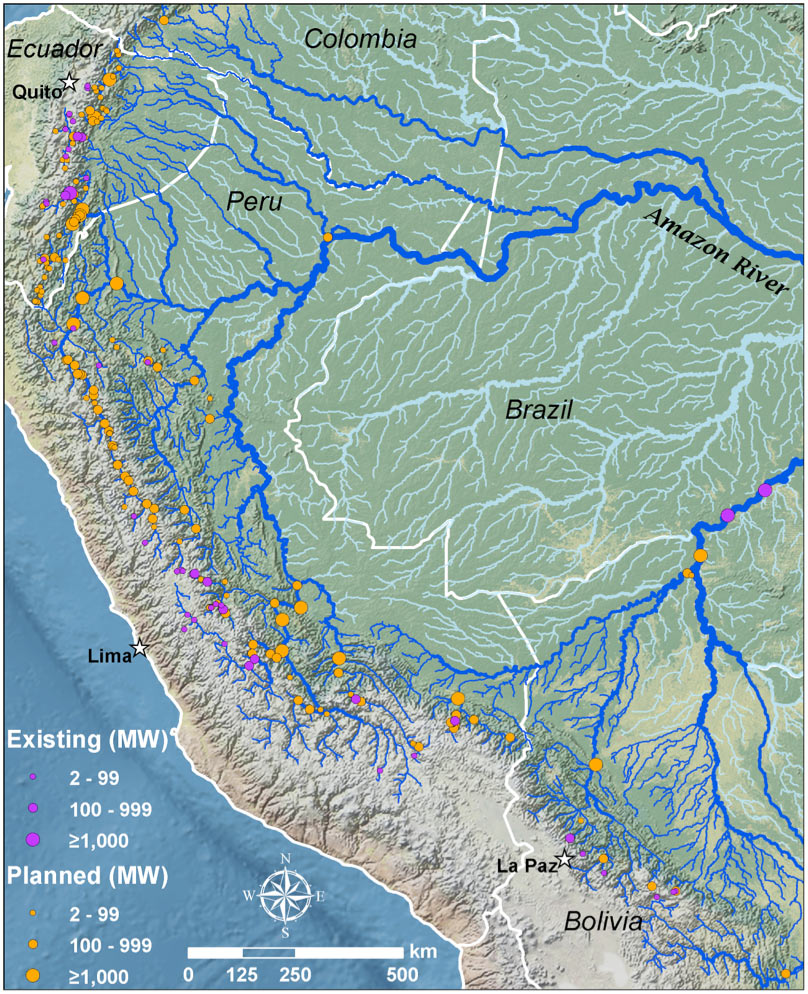

As South American countries begin to move beyond fossil fuels, many are looking to hydropower. The rivers flowing from the Andes Mountains down into the Amazon basin could provide a wealth of liquid potential to meet the energy demands of expanding populations, economies, and development. Current plans call for the damming of five of the six major Andean tributaries feeding the Amazon, with over 150 new hydroelectric projects slated for construction over the next 20 years. Without holistic, basin-wide planning, these dams could have devastating environmental consequences.

This dramatic proliferation of dams and its implications for Andean Amazon river ecological connectivity was explored in a groundbreaking 2012 paper published in PLOS ONE by Matt Finer and Clinton Jenkins.

The researchers examined the government portfolios of all proposed dams in the Andes-Amazon region with a generating capacity of 2 megawatts (MW) or greater. They used a broad set of environmental criteria to classify the projects, and found that 47 percent of the dams would have a high impact on the region.

Finer and Jenkins assessed 151 planned hydroelectric projects in Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and Colombia, rating them as having low, medium or high impact. Their evaluation considered whether each dam would: represent a new source of river fragmentation (in relation to the region’s 48 existing dams); disrupt the connectivity of free-flowing rivers that link Andean headwaters to the lowland Amazon; require new roads or transmission line routes; or directly cause significant environmental impacts, such as, flooding of more than 100 square kilometers (38.6 square miles) of forest, the disruption of known migratory fish routes, or encroachment on protected areas.

“Sixty percent of the dams would cause the first major break in connectivity between protected Andean headwaters and the lowland Amazon,” wrote the authors. In addition, they found that more than 80 percent of the proposed dams would likely drive deforestation due to new roads and flooding, while 11 dams would directly impact a protected area.

The break in river connectivity is particularly important. The Andes nurtures the Amazon floodplain with the vast majority of its sediments, nutrients, and organic matter. Andean Amazon connectivity also provides an unblocked migration route for numerous economically and ecologically important freshwater fish species. Any major breaks in natural connectivity could bring severe and unpredictable impacts.

Finer and Jenkins made three policy recommendations in 2012, that if implemented, could reduce the number of proposed Andean Amazon hydropower projects, along with the impacts of those that are built. Mongabay.com asked a group of experts to consider the relevance and feasibility of these policy recommendations today, and to make suggestions for moving them forward.

Recommendation 1: Amazon Basin-wide environmental assessments

The first policy recommendation by Finer and Jenkins urges that, “governments should shift from project-level environmental impact assessment to a more comprehensive assessment that looks at both basin-wide and regional impacts in order to identify the best locations for dams.”

(A) Dam impact ratings for tributaries originating in the Colombian, Ecuadorian, and northern Peruvian Andes. (B) Dam impact ratings for tributaries originating in the Bolivian and southern Peruvian Andes. Results of ecological analysis from Finer and Jenkins 2012. Click image to enlarge

(A) Dam impact ratings for tributaries originating in the Colombian, Ecuadorian, and northern Peruvian Andes. (B) Dam impact ratings for tributaries originating in the Bolivian and southern Peruvian Andes. Results of ecological analysis from Finer and Jenkins 2012. Click image to enlarge

Current environmental impact assessments focus only on individual projects, and don’t account for the placement of new dams in relation to other planned or existing dams. The problem with this approach is that the cumulative impact of several dams on one river, or in one basin, will be greater than the addition of a single dam.

“It’s an easy and very sensible recommendation to make, but seems like it would be difficult to implement,” due to the complex mix of authorities and agendas in the region, Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, the Deputy Director of the Global Water for Sustainability (GLOWS) program, told mongabay.com. The Amazon Basin includes several nations, she explained, with multiple private companies and funding agencies promoting dam development. “So the question [is] who or what entity would coordinate the assessment of connectivity impacts at a basin scale?”

Even the environmental evaluations done on individual hydroelectric projects have their flaws. A report by International Rivers released in 2013 points out that Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) are often funded by project developers, which can lead to biased studies that may not include all potential negative impacts.

“Since the urgent priority for all of these [Amazon Basin] countries is to achieve energy independence and assure their development needs and objectives are met, the idea of environmental management tends to be a new concept in many of these countries, and of little concern.” said Ecuadorian Rivers Institute Executive Director Matt Terry. In fact, “the general trend we see throughout the region is that most projects carry out environmental impact studies after the project has been completely defined, in order to justify or mitigate the decisions that were made early on in the project development cycle, without using criteria from public participation, risk assessments, or environmental sensitivity in the project design,”

Another block to region-wide management: there is currently no independent, competent authority that could take all regional and downstream impacts into consideration and make basin-wide decisions. While the already existing Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (OTCA) does represent all Amazon countries, the organization is presently playing no role in basin-wide hydroelectric project strategic planning.

Existing and planned Hydroelectric dams of the Andean Amazon. Dams sorted by status (existing and planned) and size (2–99 MW, 100–999 MW, and ≥1,000 MW capacity). From Finer and Jenkins 2012. Click image to enlarge.

Existing and planned Hydroelectric dams of the Andean Amazon. Dams sorted by status (existing and planned) and size (2–99 MW, 100–999 MW, and ≥1,000 MW capacity). From Finer and Jenkins 2012. Click image to enlarge.

Still another planning problem is the lack of baseline data on Amazonian rivers from which to make environmental assessments and monitor changes. Significantly more basic ecosystem research is sorely needed along with comprehensive oversight.

“Nature is dying a death of a thousand cuts,” in Amazonia, said Dr. William Laurance of James Cook University, “and the problem is you look at these projects one at a time in isolation from one another and you don’t see the big picture of all the cuts happening.”

Recommendation 2: A multi-national plan for free-flowing rivers in Amazonia

Finer and Jenkins strongly recommend the development of “a strategic multi-national plan to maintain free-flowing connectivity from the Andean highlands to the Amazon lowlands.”

Matt Terry underlined the importance of this recommendation: “If strategic, free-flowing, Andes-to-Amazon river corridors are not identified and preserved, there will be catastrophic repercussions for aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity in the Amazon basin,” he said. “As terrestrial habitats… become increasingly colonized, developed and fragmented, the Andes-to-Amazon river corridors provide the most important ecological connectivity at the entire watershed level.” Those corridors encompass the critical altitudinal transition zone, and the areas of interaction between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, with the greatest levels of biodiversity.

One ideal strategy for preserving Andean Amazon connectivity would be to avoid putting dams on main stem waterways, such as the Marañón, Madeira, Putumayo and Ucayali rivers. These streams would be designated “free-flowing” rivers and protected. Several experts are calling on OTCA and other key players including UNESCO, the World Bank, and the United Nations to back this concept. For this free-flowing connectivity strategy to succeed, however, funding mechanisms and incentives would need to be found.

“This is natural resource management 101,” Terry said. “First identify what you want to preserve before developing; also, know what you are willing to sacrifice. In this case, preserving natural, free-flowing connectivity for Andean Amazon watersheds needs to be a priority.”

A way forward, suggested Terry, is for UNESCO to “establish an International Wild and Scenic Rivers Program to protect emblematic rivers with outstanding resource values. A one percent tax on the revenues of all new and/or existing hydroelectric projects could contribute to a fund to finance the management of the proposed program.” Every new hydroelectric project should not only be responsible for environmental management within its area of influence, but also “be required to finance the preservation and management of a free-flowing river corridor in the context of compensatory mitigation.”

José Serra Vega, an energy consultant who specializes in the Amazon region

told mongabay.com that this policy recommendation, “would be ideal, but the problem is that Brazilian energy requirements mean that their [Brazilian]companies are ogling their neighbors’ resources.” The Brazilian company Odebrecht is heavily invested in developing mega-dam projects in Peru on the main stem of the Marañón River, for example.

Recommendation 3: Reexamine hydropower as a low impact energy source

Finer and Jenkins came to a third, somewhat surprising, conclusion. They challenge “the notion that hydropower is a widespread low impact energy source for the Neotropics.”

They explain that Neotropical hydropower dams are currently seen as a means of sharply reducing fossil fuel use and of curbing climate change. As a result, such projects are well supported by international financial institutions and receive the carbon credits offered by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as created by the Kyoto Protocol agreement.

However, the researchers strongly urge nations and international institutions to consider broader environmental impacts when evaluating hydropower projects. In light of their findings – with nearly half the proposed dams having high impacts on ecological connectivity, and only 19 percent having low impacts – they proposed that many of the high impact projects be cancelled.

“Otherwise, tropical rivers and forests may increasingly be at risk from otherwise well-intentioned strategies to mitigate climate change,” they wrote. “Andean nations could meet a substantial percentage of expected energy needs by prioritizing [and constructing] only low, and perhaps moderate, impact dams.” The non-Amazonian watersheds of Brazil, Peru and other countries in the region also possess substantial untapped hydroelectric potential for low and moderate impact projects.

Climate change could disrupt Neotropical hydropower plans in a major way. Drought, expected to increase as global temperatures rise, could cripple dam generating capacities. Brazil already generates nearly two-thirds of its electricity from hydropower, and controls the second largest hydroelectric project in the world, the 14,000 MW Itaipu dam on the Brazil-Paraguay border. Unfortunately, severe drought in recent years has forced Brazil to import electricity at very high prices, mostly from Argentina. In the past year alone, drought resulted in a major drop in hydroelectric generation and in dangerously low water levels in reservoirs. Some predict this situation will worsen in the near future. This could increase the pressure to plan more hydroelectric projects to generate more energy in neighboring countries, no matter the cost to ecosystems and local people.

“I think the problem,” said Dr. William Laurance, “is these nations are determined to have abundant energy and economic growth and they want energy for mining infrastructure and other reasons. There are not a lot of safe and easy economically viable alternatives, unfortunately. I do think hydropower, especially in the context of developing these relatively pristine areas of the Amazon and Andes, is an extremely bad idea. That leaves ideas of concentrating dams in areas where there is already substantial hydro development and also looking for energy conservation and for renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power.”

Flying almost blind into a hydropower future

The ominous environmental threat outlined by Finer and Jenkins has grown more worrisome since they did their work. As of May 2014, there are 412 hydroelectric dams in operation, under construction or planned for the Amazon basin and its headwaters, which could potentially lead to the “end of free-flowing rivers”, and contribute to “ecosystem collapse”, reports The Guardian newspaper –

256 are in Brazil, 77 are in Peru, 55 in Ecuador, 14 in Bolivia, six in Venezuela, two in Guyana, and one each in Colombia, French Guyana and Surinam. The number of projects in the Andes Amazon still stands at 151 dams.

While the majority of researchers and experts who spoke with mongabay.com felt that the connectivity study was a major step forward, not all agreed to its value. Dr. Asit Biswas, Founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management gave little credence to the findings or their usefulness: “After spending some 30 years in [the Amazon], I am still trying to understand the problems, issues and solutions, both in terms of people and their needs and environmental protection,” he said.

Matt Finer worries that the research, though useful, has not reached its intended audience, policy makers. “I don’t think the central messages in the paper have really gotten through to them yet unfortunately,” he said. “So there is still a lot of work on the end of civil society and researchers to make sure these messages do get through in time.”

Countries in the Andes Amazon Basin are advancing hydropower as the centerpiece of their energy strategy, and they are moving aggressively forward with plans to dam the region’s free-flowing rivers. While the policy recommendations put forward by Finer and Jenkins in 2012 remain relevant and important today, implementing them will be undeniably difficult when placed against the pressing national energy agendas of Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia and other countries.

Clearly there is a need for more research, increased cooperation, and strategic, holistic planning and management if these nations are to harvest sufficient energy while also maintaining the health and vitality of the free-flowing rivers that sustain life in the Amazon basin.

Citations:

- Finer M, Jenkins CN (2012) Proliferation of Hydroelectric Dams in the Andean Amazon and Implications for Andes-Amazon Connectivity. PLoS ONE 7(4): e35126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035126