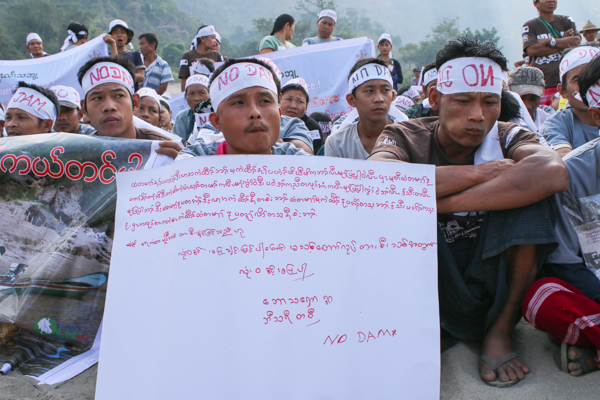

Villagers protest the proposed construction of dams on the Salween River in Myanmar, on International Day of Action for Rivers and Against Dams, March 14, 2015. At least five dams being planned on the Salween have been a flashpoint in altercations between Myanmar government forces and ethnic-minority rebel groups. Credit: Karen Environmental and Social Action Network.

Late last year, an ongoing conflict in southeast Myanmar (Burma) between members of the Karen ethnic minority group and the Myanmar government intensified over the government’s plans to build a new hydropower dam on the Salween River. The dam is one of at least five dams that the Myanmar government plans to build along the Salween.

The Irrawaddy magazine reported at the time that, according to local activists, the escalation in violence was due to an attempt by government forces to remove armed Karen militia groups from the site chosen for the Hatgyi dam.

Myanmar has been in a near-constant state of civil war since it gained independence from the UK in 1948. But the violence has lessened in recent years as the country has taken tentative steps toward resolving these long-running disputes, culminating in a draft nationwide ceasefire agreement signed on March 31 by President U Thein Sein and representatives of 16 ethnic groups.

A few days earlier, a group of activists who live on the Salween River and oppose the government’s dam plans hosted a two-day conference called “Save the Salween” in Hpa-an, the capital of the state of Karen. Paul Sein Twa, director of the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), which helped organize the conference, said in a statement emailed to mongabay.com that the conference was intended to showcase the many reasons why the Salween and its riverine communities are worth protecting, as well as to propose alternatives to the dams — all in the hopes of helping to avert a major threat to Myanmar’s fragile peace process.

“The peace process underway in Burma is the single most important issue in the country’s development,” Twa said in the statement. “Building big dams in a civil war zone can only undermine peace and breed conflict, derailing the nascent emergence of the country from more than a half century of dictatorship."

Members of the Pa-O ethnic group perform at the “Save the Salween” conference in Hpa-an, the capital of the state of Karen on March 27, 2015. The conference highlighted the natural and cultural value of the Salween River, as well as alternatives to the five dams being planned on the Salween. Credit: Karen Environmental and Social Action Network.

Even as the ceasefire agreement was being negotiated, the Myanmar army was increasing its presence in the states of Mon, Kayah, Karen and Shan, where the dams would be built and where hundreds of thousands of refugees remain dispossessed and unable to return home after decades of conflict, Twa said.

“Dam building appears to be part of a militaristic state strategy of cementing control over resource-rich ethnic minority and indigenous people’s lands,” Twa said.

Rich fisheries and fertile farmland threatened

The Salween is one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the world, running 2,800 kilometers (1,740 miles) from the mountains of the Tibetan Plateau through parts of China, Myanmar, and Thailand and emptying into the Andaman Sea.

“As the longest undammed river in mainland Southeast Asia, the Salween River sustains rich fisheries and fertile farmland that are central to the lives of many ethnic minority communities living along its banks,” states the website of the California-based conservation group International Rivers. Some 10 million people live off of the Salween River, including numerous ethnic minority groups such as the Karen, Nu, Lisu, Shan, Karenni, Wa, Tai, Mon, and Yintailai peoples.

International Rivers’ website contends that the dams “are being planned in complete secrecy, with no participation from affected communities and no analysis of the cumulative impacts or seismic risks of these projects.”

There were once plans for as many as seven dams on the Salween in Myanmar, and at least 13 more further upstream in China, according to a map developed by International Rivers. But Twa of KESAN told mongabay.com that only five of the Myanmar projects are still “actively under discussion”: Hatgyi in Karen state, Ywathit in Karenni, Mong Ton (a.k.a. Tasang) in central Shan state, and Nong Pha and Kunlong, both in northern Shan state.

The proposed dams would do irreparable damage to the Salween Basin, which extends across, China, Myanmar, and Thailand, Twa said. The basin is “home to the world’s last great teak forest, to dry-season islands rich with crops, and to healthy fisheries upon which many people depend,” he told mongabay.com. “This is a river of vast ecological and cultural value, and it is worth preserving for present and future generations.”

The dams also pose a threat of catastrophic flooding should the region’s seismic activity lead to an earthquake-induced dam failure, Twa said.

Children at a protest against proposed dams on the Salween River in Myanmar. Credit: Karen Environmental and Social Action Network.

Saw Kyaw Hla, a resident of Mikayin village along the Salween River in Karen state, attended the Save the Salween conference to emphasize how much her people depend on the river. “The Salween River is important for our livelihood, for our survival,” she said in a statement that KESAN sent to mongabay.com. “The river provides us with food, drinking water, and irrigation water to grow our crops. The income we earn from farming along the Salween allows us to send our children to school.”

KESAN’s Twa said the conference was also organized as a message to the companies from Myanmar, China, and Thailand that are partnering with the Myanmar government to build the dams. Up to 90 percent of the electricity they generate would be exported to China and Thailand, he said.

International Rivers’ Pianporn Deetes wrote in a February blog post that Myanmar has begun to attract the attention of foreign investors and the World Bank Group, ever since trade sanctions were lifted after the ruling military junta began relinquishing control to a civilian government elected in 2010. But Deetes warned that investors should be wary: “While electricity from Burma might look cheap for investors from the outside, there are many invisible costs both environmental and social which are not taken into account, the majority of which will be borne by the poorest communities, including the millions of refugees throughout the country.”

Among the alternatives that should be considered, according to Deetes, are distributed energy generation technologies, which would bring power to local communities both figuratively and literally. “If the government and the World Bank Group genuinely aim to bring electricity to the local population, decentralized off-grid solutions are the best option, not large-scale hydropower dams for export.”

Anti-dam villagers protest along the Salween River in Myanmar, on International Day of Action for Rivers and Against Dams, March 14, 2015. Credit: Karen Environmental and Social Action Network.