- Presenting a workshop on ecosystem services to a roomful of priests in Ethiopia may seem like an unlikely scenario for a conservation biologist to end up in, but for Meg Lowman, it’s an essential part of spreading her passion for bottom-up conservation.

- “Canopy Meg,” as she’s fondly referred to by her colleagues, believes in the power of local communities to be part of the solution, often in ways that are more effective than researchers can make alone.

Presenting a workshop on ecosystem services to a roomful of priests in Ethiopia may seem like an unlikely scenario for a conservation biologist to end up in, but for Meg Lowman, it’s an essential part of spreading her passion for bottom-up conservation. “Canopy Meg,” as she’s fondly referred to by her colleagues, believes in the power of local communities to be part of the solution, often in ways that are more effective than researchers can make alone.

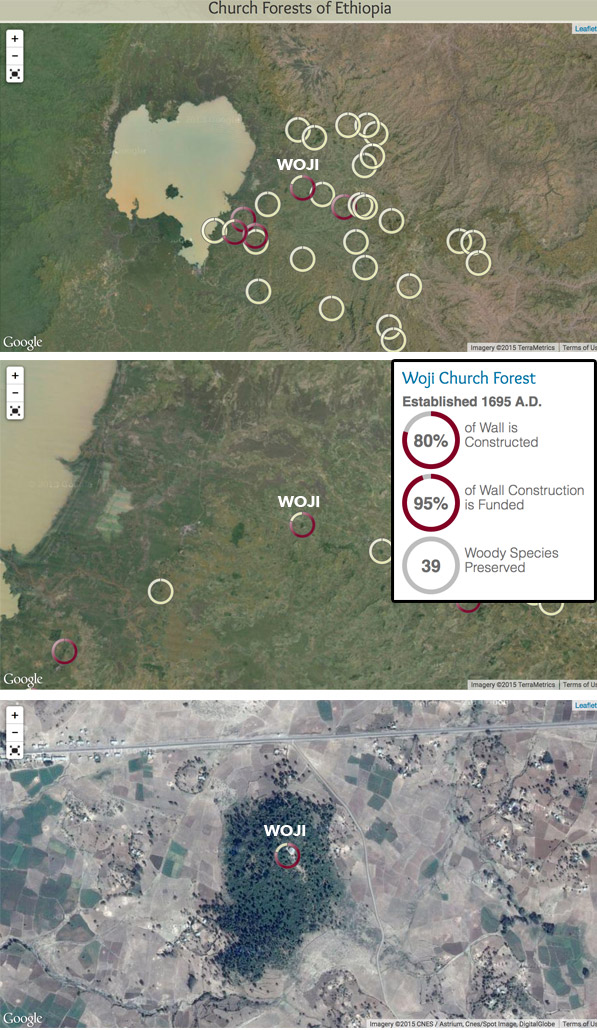

“I thought long and hard about how to help the priests save their dwindling forests,” Lowman, who is the science and sustainability director for the California Academy of Sciences, told mongabay.com. “They needed some type of perimeter delineation (i.e. fence) but they could not afford it. I tried to garner a big donation from a fencing company without success. On my return trip, the priests were very excited to share a ‘surprise’ with me! Of their own volition, they had figured out that, by taking stones out of their own local pastures, they could not only build walls to protect their church forests, but they could also raise their crop yields. Now, the people tell me that ‘their church has clothing’ when a wall is built around the forest!”

Lowman said this was one of the most rewarding experiences in her long career protecting and conserving Ethiopia’s tropical forests, a mission that often raises a few eyebrows when hearing about it for the first time.

“Most people have no idea that forest conservation challenges exist in Ethiopia and very few people are aware of the extraordinary (and depressing) landscape of northern Ethiopia,” Lowman said. And understandably so—for the past forty years, Ethiopia has experienced such severe deforestation that less than 3 percent of its original forest remains. Surprisingly, the majority of Ethiopia’s remnant forests are located around the multitudes of colorful, stone churches that dot the dusty landscape. These unexpected patches of vegetation have persisted thanks to the environmental stewardship of Ethiopia’s quietest forest guardians—the priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

The priests and Dr. Lowman share a common goal: to conserve the biodiversity of these ecologically unique “church forests.” Ethiopia’s overall biodiversity is astounding, with a 1994 inventory listing 277 species of terrestrial mammals, 862 species of birds, 201 species of reptiles, 63 species of amphibians, 150 species of fish and more than 7,000 species of plants. Moreover, a high percentage of these species are endemic; according to the inventory, 11 percent of mammals, 3.3 percent species of birds, 4.5 percent species of reptiles, 38 percent species of amphibians, and 12 percent of vascular plants are found nowhere else in the world.

The biggest threat to Ethiopia’s wildlife is deforestation due to the country’s extremely high population growth. According to data from the World Bank, Ethiopia’s population has more than tripled since 1970, standing at 94 million people as of 2013. As the population grows, so does the demand for agricultural products, fuel, timber, and living space. Data from Global Forest Watch shows Ethiopia lost over 228,000 hectares of dense tree cover through 2001 through 2012, and an FAO report predicts that the forest area will be reduced to less than 7 million hectares by 2020. Studies suggest Ethiopia’s estimated 35,000 church forests may provide safe harbor for these endangered, endemic species, underlining the importance of Lowman’s mission.

Intact forest landscapes (IFLs) are areas of undisturbed forest large enough to retain their original levels of biodiversity. According to Global Forest Watch, only two IFLs still exist in Ethiopia and a significant portion of one has been degraded since 2000. Click to enlarge.

“We are all on the same page. They want to conserve all of God’s creatures and I am trying to save biodiversity, which is one and the same,” Lowman told mongabay.com. To that end, Lowman initiated a research project in 2010 along with forest ecologist, Alemayehu Wassie Esthete, with two major objectives in mind. The first was to survey insect and tree biodiversity within 28 church forests located in the South Gondar Administrative Zone of the Amhara National Regional State.

When developing the methods for the survey, it was very important to Lowman and her colleagues to create protocols that were both inexpensive and easily replicable so that they could be taught to and utilized by anyone, with a special emphasis on school children.

“Working with Sunday schools and local schools, we can educate the youth about their own ecosystem services, since they are the leaders of tomorrow,” Lowman said.

The team’s second goal was to find solutions for building simple protective stone fences around the church forests in order to prevent further deforestation from livestock grazing and agricultural expansion. The researchers found livestock grazing significantly decreased indigenous tree seedling survival and seedling growth, underscoring the importance of controlling cattle populations as part of the effort to protect trees when they are most vulnerable. Constructing fences around the church forests proved to be an effective method to eliminate this threat, and the researchers recommend them going forward.

In addition to the insights it provided into Ethiopia’s biodiversity, Lowman said their study also resulted in a greater understanding of the perspectives local communities have for the natural world.

“Through our biodiversity surveys, we raised awareness about the important genetic library inside the church forests (including pollinators, the origin of honey, etc.),” Lowman said. “But I think that, more important than documenting the biodiversity itself, is to first and foremost conserve the forests that are home to this biodiversity. The priests, in all fairness, do not really care how many species of ants live in their forests; but they do care about saving them. As Westerners, we need to appreciate the perspective of the local people, first and foremost.”

Lowman has high hopes for the church forests of Ethiopia. She and her team helped conserve 10 of the 28 forests used in their study by building walls, and they are optimistic about finishing the rest with the continued help of local communities.” She believes this approach could be used to preserve other threatened places around the world.

“By engaging the locals and listening to their needs, we can make a big difference that may have been more effective than tackling this conservation issue with big government-down.”

Citations:

- Areaya H., Yonas M., Haileselasie T.H. (2013) Community composition and abundance of residential birds in selected forests, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia. Scientific Research and Essays, 8 (22) pp. 1038-1047.

- Bekele, M. (2001) Forestry outlook study for Ethiopia (FOSA), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Bongers F., Wassie A., Sterck F., Bekele T., Teketay D. (2006) Ecological restoration and church forests in northern Ethiopia. Journal of the Drylands: 1, 35–45.

- Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. 2014. Intact Forest Landscapes: update and degradation from 2000-2013. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Mar. 03, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Mar. 03, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org