Vanzolini’s squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis), with its distinctive black cap. Photo Credit: Arkive.

Walking through the Amazon rainforest for the first time is an overwhelming experience, and not in an entirely predictable way. With its incredible biodiversity, several orders of magnitude higher than forests in temperate zones, you can be forgiven for expecting to be surrounded by wildlife vying for your attention, from the small mammals on the forest floor to the hundreds of birds in the dappled canopy.

When you first step into the rainforest, however, it is with some surprise that you realize that despite this incredible density of living things, the forest can appear eerily uninhabited to the unaccustomed eye. In fact, you have to actually search hard for wildlife to see anything at all.

There are only a few creatures that are an exception to this rule, and squirrel monkeys are one of them. Roaming in boisterous groups of up to 150 animals, these small monkeys catch even a novice’s eye and they have a magnetic ability to keep your interest. Watching their inquisitive exploration of the forest, accompanied by the playful antics of adults and their young, is one of the more riveting experiences in a rainforest.

With their sharp black eyes set in a pale face, topped off with a distinct yellow or black cap coming to a point at a widow’s peak, squirrel monkeys are easily distinguished from other primates and can be observed across many forests in South America. That is to say, all but one species – the single exception called Vanzolini’s squirrel monkey (Saimiri vanzolinii).

Vanzolini’s squirrel monkey (Saimiri vanzolinii), feeding on nectar from flowers. Photo Credit: Arkive

For many years, particularly after renowned naturalist Philip Hershkovitz of the Field Museum in Chicago published his valuable taxonomy of Neotropical Primates, Saimiri boliviensis was considered to be a mere subspecies of the larger Bolivian squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis). Today, it has the distinction of being one of the most range-restricted primates in all of the Neotropics.

It is only found in 870 square kilometers of the Mamirauá Ecological Reserve in Brazil, and nowhere else on the planet.

Very few forests on earth can claim to be from 7 to 15 meters underwater for over half the year, but Mamirauá is one of them. Spanning 11,240 square kilometers within the Brazilian state of Amazonas, it is bounded by River Japurá in the north and east, and River Solimões in the south.

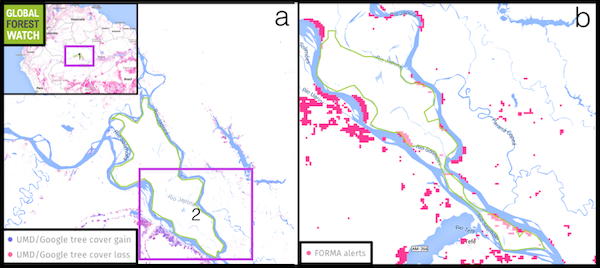

“Mamirauá is the only conservation unit in Brazil located entirely in várzea flooded forest,” reports José Márcio Ayres, of the Wildlife Conservation Society who has been instrumental in its formation, in his case study on Mamirauá for Wetlands International. The reserve includes over 499 lakes, and experiences an average of a 12-meter difference between low and high water levels through the year. It has stayed relatively stable over the last decade, with a tree cover loss of 3,635 hectares – less than half a percent of its forest – from 2001 through 2012, according to the forest-monitoring site Global Forest Watch. However, there have also been 829 FORMA alerts since 2006 within this area, which is a system that analyses satellite imagery and other factors to generate bi-monthly notifications indicating where new, large-scale forest loss has probably occurred.

Mamirauá Ecological Reserve (MM) where S. boliviensis is endemic. The other regions depicted indicate the geographic ranges of the other Saimiri groups evaluated in the study. Image adapted from Lynch Alfaro et al., 2015.

Mamirauá Ecological Reserve, with tree cover loss and FORMA alert number and location (lower-left inset) shown according to data from Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

This annual flooding has important effects on the distribution of terrestrial wildlife in the area, being suitable only for those species that are skilled swimmers. In the trees, however, arboreal primates do so well that Mamirauá boasts two endemic species (those that are not found anywhere else) – the white uakari (Cacajao calvus calvus) and Vanzolini’s squirrel monkey – as well as six other primate species, including two other subspecies of squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus cassiquiarensis and Saimiri sciureus macrodon).

This conglomeration of biodiversity – including 290 fish and 310 bird species – reaffirms Mamirauá’s role as a hotspot for speciation within the genus Saimiri and recent work on the genetics of squirrel monkeys overall has lent further support to this idea. In the January volume of the journal Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Jessica Lynch-Alfaro and colleagues utilized 118 squirrel monkey samples from 68 localities to construct a mitochondrial DNA tree. They discovered that all speciation events occurred between 1.4 and 0.6 million years ago, which predates the last three glacial maxima, eliminating climate extremes as a cause for speciation.

Interestingly, they discovered that Saimiri vanzolinii is not in fact subsumed under Saimiri boliviensis, but instead is a sister species to a eastern population of Saimiri ustus in Rondônia. The study’s results indicated that S. vanzolinii diverged from S. ustus 590 thousand years ago, which is earlier than the formation of the Mamirauá Reserve, about 5 to 15 thousand years ago.

The morphological diversity of the genus Saimiri encompassing all squirrel monkeys. Image adapted from Lynch Alfaro et al., 2015. Click to enlarge.

So how did this incredible biodiversity emerge?

Floodplain habitats, say scientists, go through incredible alterations yearly, based on erosion and sedimentation, resulting in the continuous transformation of river ways. Saimiri vanzolinii was likely endemic to a much larger area once, and has now been forced into the tiny region it occupies today, bordered by rivers on all sides.

“It is likely that S. vanzolinii has become restricted to a very small habitat because of the evolution of the floodplain forest ecology over time,” Lynch-Alfaro states in her study, “and it is also likely that all suitable remaining habitat for S. vanzolinii will be rapidly lost because of global climate change in conjunction with the inherent dynamic characteristics of floodplain forest.”

Long-term studies within the reserve also highlight the importance of this habitat for Vanzolini’s Squirrel Monkey. “The distribution of Saimiri vanzolinii,” according to Fernanda Pozzano Paim of the Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá, “constitutes extreme endemism.”

a) The geographic distribution of Saimiri vanzolinii within the Mamirauá Ecological Reserve reproduced from the range described by the IUCN, evaluated in 2008. b) The region in box 1 is the location Mamirauá Ecological Reserve; box 2 shows the newly evaluated range of S. vanzolinii according to Paim et al. (2013), showing a much more restricted range of only 870 square kilometers. Click to enlarge.

The Mamirauá Reserve has already been selectively logged, with many hardwood trees sold for timber. Mamirauá has 2,100 human inhabitants living in 14 communities that extract resources from the Reserve and participate in its management. Animals that are hunted within the Reserve include the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) and the manatee (Trichechus inunguis, after whom the reserve is named), both of which are illegally hunted to this day.

One study on the effects of tourism on primate sightings revealed that while some larger primates were rarely observed on high-use trails, Saimiri vanzolinii, listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN, did not appear to be affected by tourism. Scientists have concluded that sightings of Saimiri are sufficiently high, indicating the tourist visitation rates within the reserve are sustainable, but the monkeys still maintain their flight responses when disturbed. Today, the Mamirauá Reserve maintains this delicate balance with careful monitoring, perhaps the only safeguard of the future of Saimiri vanzolinii.

Citations:

Alves, D. M., & Brito, D. (2013). Priority mammals for biodiversity conservation in Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science, 6(4), 558-583.

Ayres, J.M., Lima-Ayres, D., Albernaz, A. L., Marmontel, M., Queiroz, H. L., Barthem, R. B., Alves, A. R., Moura, E., Silveira, R. D., and Santos, P. Mamirauá: The Conservation of Amazonian Flooded Forests. In Community Involvement in Wetland Management. 105.

Costa, L. P., Leite, Y. L. R., Mendes, S. L., & Ditchfield, A. D. (2005). Mammal conservation in Brazil. Conservation Biology, 19(3), 672-679.

Hammer, Dan, Robin Kraft, and David Wheeler. 2013. “FORMA Alerts.” World Resources Institute and Center for Global Development. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Feb. 20, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “UMD Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland and Google. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Feb. 20, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.com.

Paim, F. P., Aquino, S. P., & Valsecchi, J. (2012). Does ecoturism activity affect primates in Mamirauá Reserve?. UAKARI, 8(2), 41-48.

Paim, F. P., Valsecchi, J., Harada, M. L., & de Queiroz, H. L. (2013). Diversity, geographic distribution and conservation of squirrel monkeys, Saimiri (Primates, Cebidae), in the floodplain forests of Central Amazon. International Journal of Primatology, 34(5), 1055-1076.

Related articles

|

$7 million could save lemurs from extinction

(02/25/2015) Last year, scientists released an emergency three-year plan that they argued could, quite literally, save the world’s lemurs from mass extinction. Costing just $7.6 million, the plan focused on setting up better protections in 30 lemur hotspots. However, there was one sticking point: donating to small programs in one of the world’s poorest countries was not exactly user friendly. |

|

No experience necessary: how studying tamarins led to an innovative research organization in the Amazon

(01/15/2015) While conducting doctoral research on tamarin reproductive biology in the Peruvian Amazon, Mrinalini Watsa realized she needed help in the field. Rather than hiring seasonal assistance she, along with Gideon Erkenswick, decided to create a life-changing non-profit organization, PrimatesPeru. The new NGO would allow students to conduct field research in one of the most biodiverse, yet threatened, places on Earth. |

|

Monkey sleep, monkey do: how primates choose their trees

(12/31/2014) Primates don’t monkey around when deciding where to spend the night, but primatologists have had a poor grasp on what drives certain monkeys toward specific trees. Now, two extensive studies of Indonesian primates suggest that factors in selecting trees each evening are site-specific and different for each species—and that some overnight spots result in conflicts between monkeys and humans. |

|

Camera traps capture rare footage of wild bonobos (video)

(12/29/2014) Bonobos, our ape cousins, love peace. Unlike chimpanzees, also our close relatives, bonobos are known to resolve conflict through sex instead of aggression. They kiss, they caress, and females display genito-genital rubbing (also called G-G rubbing) to communicate, bond, and reconcile. |

|

Tribal violence comes naturally to chimpanzees

(12/08/2014) It all went to hell when Jane Goodall started handing out bananas. Within a few years, the previously peaceful chimpanzees she was studying split into two warring tribes. Gangs of males from the larger faction systematically slaughtered their former tribemates. All over the bananas. Or so the argument goes. |

|

New calendar celebrates primates and raises money for their survival

(11/26/2014) Humans, or Homo sapiens sapiens, are really just upright apes with big brains. We may have traded actual jungles for gleaming concrete and steel ones, but we are still primates, merely one member of an order consisting of sixteen families. We may have removed ourselves from our wilder beginnings, but our extant relatives—the world’s wonderful primates—serve as a gentle living reminder of those days. |

|

Local people are not the enemy: real conservation from the frontlines

(11/12/2014) Saving one of the world’s most endangered primates means re-thinking conservation. When Noga Shanee and her colleagues first arrived in Northeastern Peru on a research trip to study the yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda), she was shocked by what she observed. |