Modern day expeditions face a collection dilemma as scientists consider ethics and endangerment

A tray of Eriocnemis (a genus of hummingbird) specimens, Swedish Museum of Natural History – Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet,Stockholm, CC BY-SA 3,0 License, Wikimedia.

In 1912, a group of intrepid explorers led by Rollo and Ida Beck, widely acknowledged to be the foremost marine bird collectors of their time, embarked on a most remarkable effort to catalogue South America’s oceanic birds. Museums of the day held opportunistically collected specimens from scattered sources, but rarely did these include truly pelagic, or ocean-bound, birds that spent little time near the coast. A comprehensive collection of species was critical to resolving questions on the birds’ phylogeny or family tree, but was conspicuously absent, thus giving rise to the Brewster-Sanford Expedition of 1912.

Dr. Leonard Sanford, a trustee of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), with the financial support of Frederick Brewster, hired the Becks to lead the five-year expedition. Beginning in Peru, the Becks traversed the entirety of the South American coast, collecting specimens in Cuba and the Caribbean on their way back to the United States. This Herculean effort culminated in the import of 7,853 dead bird specimens to the AMNH.

Robert Cushman Murphy, who wrote in some detail about the expedition, writes that the Becks collected widely, not just of suspected new species but of known species as well, to create a comprehensive collection.

“The collection is, naturally, more notable for its full representation of the South American sea bird fauna, including hitherto little known rarities, than it is for forms new to science,” he wrote at the time. But this expedition represents only a tiny drop in the bucket of specimens collected thus far.

Ever since scientists began systematically cataloguing life on Earth, museums, universities, zoos, and private collectors have mounted scores of collecting expeditions across the planet. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History contains 126 million specimens, from fossils to thousands of preserved birds, insects and mammals, the bulk of which have never been seen by the public. The Field Museum in Chicago has 24 million specimens, and similar collections abide in the libraries and vaults of dozens of research institutions all over America and the world.

Rollo Beck preparing a bird specimen from the Brewster-Sanford Expedition . Photo by: American Museum of Natural History.

Recently however, the principal of collecting voucher or holotype specimens—the physical body of a newly suspected species—has come under serious scrutiny. Ben Minteer, the Arizona Zoological Society Chair at Arizona State University, along with colleagues at Plymouth University made a strong, but controversial, case for reduced voucher specimen collections in a plea published in the journal Science in April of this year.

“Collecting specimens is no longer required to describe a species or to document its rediscovery, ” asserted Minteer, especially in the case of rare or threatened species. He described technological advancements, such as high-resolution images, sonograms, or molecular sampling, which can allow for species recognition without increasing extinction risks by killing individuals in the wild.

Yet, most research communities still insist on preserved specimens as the gold standard for publishing descriptions of new species or documenting a species’ existence in a particular geographic location.

The situation is a complex one. Sometimes, species identifications can absolutely necessitate a voucher specimen, such as in the case of distinguishing frog species that share many similarities in observable morphology. In other cases, such as the recent discovery of a new leopard frog species, Rana kauffeldi, in New York City, it appears that a holotype was obtained on protocol, despite photography, measurements, and vocalizations being recorded for up to 283 specimens. Such requirements vary from field to field.

Geoff Gallice is an entomologist at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the University of Florida. In an interview with mongabay.com he said nearly all insect species are hugely abundant, with only a select few facing acute population declines. These rare creatures, however, are often subject to pressure from amateur collectors who use targeted and highly efficient capture methods to collect them for reasons unrelated to science. Unlike these unscrupulous collectors, he argues, scientific collectors would be acutely aware of the dangers of over collection.

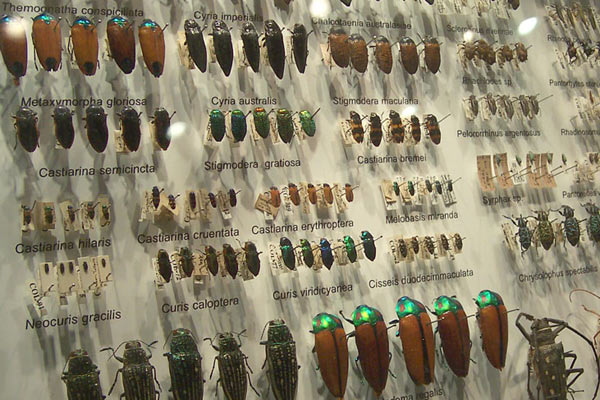

Beetle collection at the Melbourne Museum, Australia. Here, each beetle species is represented by half a dozen individuals. Photo by: Creative Commons 3.0.

“There is basically no evidence that any amount of collecting for scientific purposes has any effect on insect populations, anywhere,” argued Gallice. When he embarks on a project, Gallice says his goal is often to collect every single animal of the focal group that he is studying.

“This is because it is impossible to identify many species based on visual observation or even high-resolution photographs,” he noted. “Often the detail required to differentiate cryptic species lies only in minute differences in the DNA, and unfortunately specimens must be destroyed to gather genetic material.”

This is however a difficult concept to swallow, and Piotr Naskrecki, an entomologist with the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, recently felt the full force of public opinion on the subject. On a recent biodiversity survey in Guyana, at a site never studied before, he discovered a remarkable specimen of Theraphosa blondi, the largest spider in the world. Naskrecki described his encounter with the animal, commonly known as the Goliath birdeater, on his blog to high acclaim. But when Naskrecki later admitted to a reporter that the specimen was euthanized for a museum collection, he received a sudden backlash with commenters labeling the act as both cruel and unnecessary.

Naskrecki wrote a moving response to his critics, justifying the need for the specimen. The Goliath birdeater is not endangered in any way.

“A scientist picking up one spider is no different from a bird doing the same,” writes Naskrecki on his blog, “if a stochastic event such as this can drive a species to extinction then this species is already doomed.”

Theraphosa blondi, the goliath birdeater, the largest spider in the world. Photo by: Berichard/ Creative Commons 2.0.

Both Naskrecki and Gallice agree that collecting physical specimens is critical to the study of natural history, ecology, and evolution.

“It may be ironic,” Gallice said, “but the only way we will be able to protect biodiversity in a changing world will be through a thorough understanding of the distribution of biodiversity across the planet, and the only practical way to achieve that is through the study of collections.”

The fact that the death of the Goliath birdeater received such outrage is unusual, for it is safe to say that spider killings, like insect killings, rarely give rise to feelings of empathy as would the death of a tropical bird, for example. Yet, even the deaths of charismatic animals for research is rarely reported by the media or divulged by scientists outside of their research papers—the collection of a

holotype of Rana kauffeldi is a case in point.

So, how do collection rules apply to larger organisms, with longer lifespans and more classically charming appearances?

Sean Williams is an ornithologist based at the Department of Zoology at Michigan State University, and he asserted that it is indeed possible for endangered birds to be affected by indiscriminate collecting policies, which are no different than other threats birds might face, such as hunting or habitat destruction. However, Williams is firm in his defense of the ornithological collection system for science.

“I am not aware of any collection practices that are indiscriminate,” said Williams in an interview with mongabay.com, describing rigorous collection permit screening, and rules set by local governments that do not allow for collection without pre-approval.

Study skins of Eurasian jays at the Berlin Naturkundemuseum. Photo by: LoKiLeCh/Creative Commons 3.0.

When faced with a potentially new discovery, Williams said that the distinctiveness of the bird then determines the collection protocol used. Photographs and measurements can be used to identify a distinctive new species, while cryptic new species might require a skull or other internal measurements that force the collection of a specimen.

“However, there are so many measurements on an animal that could be taken, [that] it [can] be almost impossible to get these measurements on a live bird,” said Williams, “and the amount of stress the bird would endure during the process of being handled for so long may not be humane.”

Thus the decision to collect is often based on collection protocols, permits, and strong evidence for the need for a specimen—and of course, the personal ethics of the collector during the study, since most studies are carried out at remote sites without direct supervision.

Furthermore, specimens may hold great value beyond the moment in which they are collected—they are carefully preserved for reference by scientists in the future to address broad questions that span multiple species, much like building a puzzle with different parties contributing individual pieces to the whole over centuries. New species have even been described based solely on specimens collected decades before—without the researcher ever stepping foot outside the museum.

The Field Museum in Chicago’s Rapid Biological Inventory (RBI) team is one of the world’s last few scientific teams that target unknown areas for biodiversity surveys.

“Some representative plant, fish, amphibian, and reptile specimens are collected,” said Nigel Pitman, a Mellon Senior Conservation Ecologist at the Museum, who had only just returned from the 27th RBI conducted within Peru’s Tapiche-Blanco region. “Birds and mammals are never collected.” All fish, reptiles, and amphibians collected are deposited in local museums, as per regulations. Most identification happens directly in the field, by the experts in various taxonomic groups that comprise the collection team.

As a botanist, Pitman finds that voucher specimens are vital and that museum collections still do not have enough specimens to truly understand species distributions and variability in the tropics. Due to nearly constant changes in tropical plant taxonomy, it is crucial for him to obtain a representative specimen, because it is quite likely that the species will require a revision or possible alteration in the future. Without the specimen itself it would be impossible to revise taxonomies.

“We’re better off focusing on the well-documented threats that are tearing the Amazon apart—illegal logging, overfishing, overhunting, agricultural clearing, fires, road-building, etc.,” said Pitman. According to him, Minteer’s claim that most discoveries have already been made and placed in museums is dead wrong for the group he studies—Amazonian trees—as most RBIs turn up new plant discoveries.

There are two concerns typically at play in the discussion of whether collection of specimens is a necessary feature of biological expeditions. The first is whether the collection harms the species itself, furthering its overall demise in an area, and the second is the ethics of euthanizing a living creature for the advancement of science. While collecting plant species rarely results in the demise of entire trees, scientists that study birds, mammals, and insects are often faced with the difficult decision of whether to collect a voucher specimen.

Type specimen of a female white-spotted Agrias subspecies (Agrias amydon phalcidon). Photo by: Ricoh Caplio/Creative Commons 3.0. |

Collection in tropical areas is subject to rigorous scrutiny by local forestry departments, and exporting samples for science is a complicated process littered with checkpoints to check and re-check all biological materials that cross borders. All those interviewed for this article agreed that euthanizing specimens was an extremely difficult thing to do, and often a task not relished by those performing the procedures—after all, these scientists have devoted their lives to the study and protection of these very creatures. The tendency, therefore, is not to collect unless necessary as determined by the goals of the study. Meanwhile technological advancements are being utilized in a way that Minteer and colleagues encourage, albeit slowly.

In 2006, Ramana Athreya, discovered a new species of an Asian babbler of the genus Liocichla in the state of Arunachal Pradesh in India. This scientist chose to take a series of detailed photographs, recordings of vocalizations, and feathers alone—with no voucher specimen. From these alone, he reported the discovery in a formal publication—an achievement Minteer and colleagues applaud. However, while these measures were used to verify the new species (Liocichla bugunorum sp nov), the final confirmation ironically came from a comparison to a holotype specimen held at a museum.

Conversations on collections such as Naskrecki’s Goliath bird eater, for example, are an important part of the process of science communication. The alienation of the public from scientists in their laboratories can be a real threat to the scientific enterprise. Governmental restrictions control the numbers of species removed from the wild, but in many cases, scientists themselves make final choices within the limits of their protocols.

“I regard each person that I know has collected as incredibly knowledgeable of the species in the collecting area,” Williams asserted. “They are all so passionate about birds and their conservation, bordering on insanity, that I would not think they would do anything that has even the slightest chance of putting a population at risk.”

An array of zoological specimens at the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo. Museums gain specimens not just from scientists, but also from collectors and hunters who sometimes donate their specimens. Photo by: Public Domain.

Collection of spiders at Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. Many museum collections are never seen by the public, but still play a role in ongoing research. Photo by: Hannes Grobe/AWI/Creative Commons 3.0.

Citations:

- Athreya, Ramana. “A new species of Liocichla (Aves: Timaliidae) from Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh, India.” Indian Birds 2.4 (2006): 82-94.

- Minteer, Ben A., et al. “Avoiding (Re) extinction.” Science 344.6181 (2014): 260-261.

- Murphy, Robert Cushman. “Oceanic birds of South America”. American Museum of Natural History (1936).pp 1245

Related articles

Gone for good: world’s largest earwig declared extinct

(11/19/2014) The world has lost a giant: this week the IUCN Red List officially declared St. Helena giant earwig extinct. While its length of 80 millimeters (3.1 inches) may not seem like much, it’s massive for an earwig and impressive for an insect. Only found on the island of St. Helena in the remote southern Atlantic, experts believe the St. Helena giant earwig was pushed to extinction by habitat destruction.

Egyptian art helps chart past extinctions of big mammals

(12/01/2014) Life in modern Egypt clings to the Nile River. This crowded green strip within the desert supports more than 2,300 people per square kilometer (6,000 per square mile). But 6,000 years ago, all of Egypt was green and vibrant, teeming with life much like the current Serengeti. Over time, this rich ecosystem fell apart.

Meet the world’s rarest chameleon: Chapman’s pygmy

(11/25/2014) In just two forest patches may dwell a tiny, little-known chameleon that researchers have dubbed the world’s most endangered. Chapman’s pygmy chameleon from Malawi hasn’t been seen in 16 years. In that time, its habitat has been whittled down to an area about the size of just 100 American football fields.

Chameleon crisis: extinction threatens 36% of world’s chameleons

(11/24/2014) Chameleons are an unmistakable family of wonderfully bizarre reptiles. They sport long, shooting tongues; oddly-shaped horns or crests; and a prehensile tail like a monkey’s. But, chameleons are most known for their astonishing ability to change the color of their skin. Now, a update of the IUCN Red List finds that this unique group is facing a crisis that could send dozens of chameleons, if not more, to extinction.

The Search for Lost Frogs: one of conservation’s most exciting expeditions comes to life in new book

(10/30/2014) One of the most exciting conservation initiatives in recent years was the Search for Lost Frogs in 2010. The brainchild of scientist, photographer, and frog-lover, Robin Moore, the initiative brought a sense of hope—and excitement—to a whole group of animals often ignored by the global public—and media outlets. Now, Moore has written a fascinating account of the expedition: In Search of Lost Frogs.

Top scientists raise concerns over commercial logging on Woodlark Island

(10/21/2014) A number of the world’s top conservation scientists have raised concerns about plans for commercial logging on Woodlark Island, a hugely biodiverse rainforest island off the coast of Papua New Guinea. The scientists, with the Alliance of Leading Environmental Scientists and Thinkers (ALERT), warn that commercial logging on the island could imperil the island’s stunning local species and its indigenous people.

Extinction island? Plans to log half an island could endanger over 40 species

(09/22/2014) Woodlark Island is a rare place on the planet today. This small island off the coast Papua New Guinea is still covered in rich tropical forest, an ecosystem shared for thousands of years between tribal peoples and a plethora of species, including at least 42 found no-where else. Yet, like many such wildernesses, Woodlark Island is now facing major changes: not the least of them is a plan to log half of the island.