This is the second article in a two-part series examining the situation of the Hainan gibbon and what’s being done to save it from becoming the first gibbon species to go extinct in modern times. Read the first part here.

Critically endangered and endemic to China’s southernmost province of Hainan, only around 30 Hainan gibbons (Nomascus hainanus) survive today. Rapid island-wide deforestation and consequential loss of habitat, uncontrolled hunting, and failed captive breeding attempts have pushed this ape towards the precipice of becoming the first primate species to go extinct in the modern world.

To hash out a plan to save the Hainan gibbon, international experts in primates convened an emergency meeting in Hainan earlier this year.

“The workshop identified four different broad priority areas that are most important in affecting the likelihood of Hainan gibbon survival – current constraints to gibbon population growth; current constraints to habitat quality, availability and connectivity; impacts of human activities; and ineffective communication and collaboration between stakeholders,” Dr. Samuel Turvey, Senior Research Fellow at the Zoological Society of London and an expert on past and present mammal extinctions, told mongabay.com.

“For each of these areas, we identified major threats to gibbon survival, the goals required to address each threat, and the short-term and long-term management and research actions that are needed to achieve these goals.”

Hainan gibbon with infant. Photo by Bill Bleisch, FFI.

He said there is hope that the workshop’s recommendations can be used as the basis for the first Chinese government-approved Species Action Plan for the Hainan gibbon, “which will provide important political leverage to support the next conservation steps for the species.”

But the solution goes beyond in-situ conservation measures. Turvey said it is imperative to raise awareness of the species and its plight both in China and globally. “It’s disconcerting to realize how few people, even those working in conservation, are aware that it’s probably the world’s rarest mammal species,” Turvey said.

Based on his expertise in mammalian and human-caused extinctions, Turvey said a conservation strategy that ensures the future survival of the species must involve multiple components and close collaboration between different stakeholders – as well as an “intensive” management component.

“Monitoring of the current gibbon social groups will have to be optimized, with information about movements, ranging behavior and habitat use then used to make further management recommendations,” Turvey said, adding that “a formally ratified ‘emergency response plan’ containing clear recovery actions needs to be set up in case any further population decline is detected.”

Remaining forest in Hainan’s mountainous west. Photo by Anna Frodesiak.

According to Turvey, immediate conservation action should focus on increasing and connecting available habitat in the gibbons’ last refuge of Bawangling National Nature Reserve.

“Increasing available habitat is likely to involve a mixture of forest regeneration, probably forest corridors between neighboring fragments in the first instance, in tandem with more rapid solutions such as canopy bridges to encourage gibbons to move short distances between separate fragments,” Turvey said. “Any kind of potential hunting threat or disturbance to the gibbon forest at Bawangling also has to be eliminated entirely.”

With so few individuals remaining worldwide, Turvey said it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how many gibbons would be needed to make up a viable population and ensure the long-term survival of the species. Results from modeling analyses suggest the gibbons may be safe from extinction for the next couple of decades if their numbers cease declining. However, even with a stable population size, inbreeding will inevitably become a problem if forest fragmentation prohibits the mixing of sub-populations. Inbreeding can cause harmful traits to crop up in a population, reducing its chances of long-term survival. To counter this, it is “imperative that the population grows and expands into large forested areas very quickly,” Turvey said.

In addition to the risks of inbreeding, Turvey cautioned its restricted habitat means that even a single event like a typhoon or disease outbreak could be catastrophic and eliminate the entire species.

From 2001 through 2012, the island of Hainan lost more about 7 percent of its dense tree cover, according to data from Global Forest Watch.

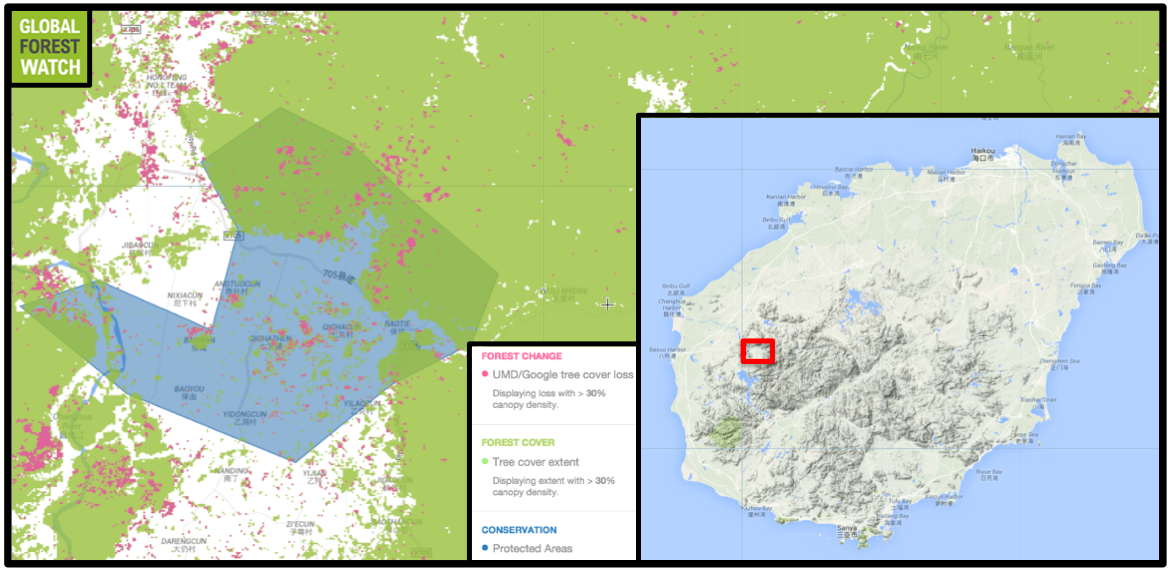

No large areas of intact forest currently exist on Hainan, with what forest remains concentrated in the western part of the island. According to Global Forest Watch, Hainan lost approximately 142,000 hectares of lush tree cover (although some of this may be attributable to plantation harvesting) from 2001 through 2012, representing about 7 percent of its forest cover as of 2000. Hainan gibbons are found in the region indicated by a yellow circle. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Bawangling National Nature Reserve is the only place in the world where Hainan gibbons have be found. Yet it is only partially forested, with fragments interspersed with open land. According to Global Forest Watch, Bawangling lost approximately 152 hectares of tree cover from 2001 through 2012–or nearly 8 percent of its forested area–despite its status as a protected area. Map courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Despite the gravity of the situation facing the rarest primate alive today, Turvey has reason to be optimistic about the future of the Hainan gibbon.

“Given the right management decisions and commitment from stakeholders and authorities – which I believe we have – then the Hainan gibbon should still be able to recover from its current dire situation,” he said.

However, saving the species will be no small feat, requiring cooperation between international agencies, local and national governments, communities and experts for one common goal.

“Working with multiple stakeholder groups – especially ones with varying levels of appreciation of previous approaches for recovering critically small populations or the threats such populations are likely to face – is inevitably going to be an involved process; indeed, making sure that all possible conservation recovery actions are fully considered, that the best expertise is consulted, and that everyone’s ideas and concerns are taken on board when thinking about potentially sensitive or long-term activities, will always take time to do properly,” Turvey said.

A rubber tree being tapped at a rubber plantation in Hainan. Clearing of forest for rubber was a significant contributor to the island’s overall deforestation. Photo by Anna Frodesiak. |

On a lighter note, he said, “In practice, this means lots of trips to Hainan, which is a very interesting place to be able to visit – it’s always a privilege to be able to get to Bawangling again. At least it means that my Mandarin has improved!”

A few years ago, when Turvey visited Bawangling, he had the fortune of seeing five Hainan gibbons. Recounting the memorable experience, he said, “We spent the night in the forest in order to get up at 4 a.m. and climb to the top of one of the ridges by dawn, so that we could listen for the gibbons singing and rush down to find them. Seeing the world’s rarest mammal species up close in the wild is an unforgettable experience. They are such beautiful animals, and move effortlessly through the canopy.”

“Watching them was made more poignant by the fact that the gibbons themselves don’t realize how rare they are – they’re oblivious to their plight – and this really reinforces that they cannot be allowed to go extinct,” Turvey said.

He hopes the Hainan gibbon will be used, in the future, as an example of a successful conservation story. But as of now it cannot be known whether the world’s rarest primate will spring from the brink of extinction like the Chatham Island black robin (Petroica traversi) or the Mauritius kestrel (Falco punctatus), or whether it will succumb to human pressure and go the way of the dodo. Only time—and effort—will tell.

Citations:

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Dec. 17, 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.

Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R. A., Rylands, A. B., Taylor, L. A., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E. A.,

Wallis, J. and Clark, F. E. (eds.). 2014. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered

Primates 2012–2014. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International

Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological

Society, Arlington, VA. iv+87pp.

Zhang, M., Fellowes, J. R., Jiang, X., Wang, W., Chan, B. P., Ren, G., & Zhu, J. (2010). Degradation of tropical forest in Hainan, China, 1991–2008: Conservation implications for Hainan Gibbon ( Nomascus hainanus). Biological Conservation, 143(6), 1397-1404.

}}

Related articles

Tribal violence comes naturally to chimpanzees

(12/08/2014) It all went to hell when Jane Goodall started handing out bananas. Within a few years, the previously peaceful chimpanzees she was studying split into two warring tribes. Gangs of males from the larger faction systematically slaughtered their former tribemates. All over the bananas. Or so the argument goes.

New calendar celebrates primates and raises money for their survival

(11/26/2014) Humans, or Homo sapiens sapiens, are really just upright apes with big brains. We may have traded actual jungles for gleaming concrete and steel ones, but we are still primates, merely one member of an order consisting of sixteen families. We may have removed ourselves from our wilder beginnings, but our extant relatives—the world’s wonderful primates—serve as a gentle living reminder of those days.

Local people are not the enemy: real conservation from the frontlines

(11/12/2014) Saving one of the world’s most endangered primates means re-thinking conservation. When Noga Shanee and her colleagues first arrived in Northeastern Peru on a research trip to study the yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda), she was shocked by what she observed.

De-protection of Protected Areas ramps up in Brazil, ‘compromises the capacity’ of ecosystems

(10/31/2014) Brazil has reserved about 17.6 percent of its land (1.5 million square kilometers) to receive protection from unauthorized exploitation of resources. However, despite significant expansions in protected areas since the mid-2000s, the formation of Protected Areas has stagnated in the country since 2009, and many have had their protections completely revoked.

(10/24/2014) Slow lorises are YouTube stars. A quick search on the website will greet you with several videos of these endearing little primates–from a slow loris nibbling on rice cakes and bananas, to a loris holding a tiny umbrella. Lady Gaga, too, tried to feature a slow loris in one of her music videos. But the loris nipped her hard, and she dropped her plans. This was probably for the best, because the bite of a slow loris is no joke. Being the only known venomous primate in the world, its bite can quickly turn deadly.

Brazil declares new protected area larger than Delaware

(10/23/2014) Earlier this week, the Brazilian government announced the declaration of a new federal reserve deep in the Amazon rainforest. The protections conferred by the move will illegalize deforestation, reduce carbon emissions, and help safeguard the future of the area’s renowned wildlife.

Gold mining expanding rapidly along Guiana Shield, threatening forests, water, wildlife

(10/22/2014) Gold mining is on the rise in the Guiana Shield, a geographic region of South America that holds one of the world’s largest undisturbed tract of rainforest. A new mapping technology using a radar and optical imaging combination has detected a significant increase in mining since 2000, threatening the region’s forests and water quality.

Coal, climate and orangutans – Indonesia’s quandary

(10/21/2014) What do the climate and orangutans have in common? They are both threatened by coal – the first by burning it, and the second by mining it. At the recent United Nations Climate Summit in New York, world leaders and multinational corporations pledged a variety of actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation to avert a looming disaster caused by global warming.