New report finds that 83 percent of recent murders of environmental activists in Peru linked to police, military, or private security guards

On September 1st, indigenous activist, Edwin Chota, and three other indigenous leaders were gunned down and their bodies thrown into rivers near the border of Peru and Brazil. Chota, an internationally-known leader of the Asháninka in Peru, had warned several times that his life was on the line for his vocal stance against the destruction of his peoples’ forests, yet the Peruvian government did nothing to protect him—or others. Unfortunately, Edwin Chota and his indigenous partners were only the latest in a longline of cold blood killings in the forests of Peru.

“We have faced violence, racism, neglect indifference, all arising from the sense of indigenous as worthless,” wrote the indigenous rights group the Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) after the murders came to light. “We are outraged at the ‘colonization’ of the forest, where indigenous peoples are killed with impunity. We are abandoned and stripped of our riches by those in search of rubber yesterday, and today by loggers, miners, oil extractors, and tomorrow anyone who has ‘power.'”

A new report by Global Witness finds that at least 57 environmental and land activists have been murdered in Peru in just 12 years, making the country the fourth most dangerous country on Earth for environmental activists, at least based on current data. The report comes just weeks before Peru hosts the next UN climate meeting in Lima, which is expected to lay the final groundwork for a new agreement in Paris 2015.

Men in the Asháninka tribe in Brazil. Photo by: Antônio Milena/Agência Brasil/Creative Commons 3.0 Brazil.

“The murders of Edwin Chota and his colleagues are tragic reminders of a paradox at work in the climate negotiations,” said Patrick Alley, co-Founder of Global Witness. “While Peru’s government chairs negotiations on how to solve our climate crisis, it is failing to protect the people on the frontline of environmental protection. Environmental defenders embody the resolve we need to halt global warming. The message is clear, if you want to save the environment, then stop people killing environmental defenders.”

Illegal logging and illegal mining are rife across Peru. In fact, illegal loggers have been charged with the murder of Chota and the three other leaders: Jorge Ríos Pérez, Leoncio Quinticima Melendez, and Francisco Pinedo.

Peru is not alone in losing so many environmental activists. A report earlier this year by Global Witness found that 908 environmental and land activists had been murdered between 2002 and 2013 in 38 countries. However, even this was likely a major underestimation. In many countries where conflict is rife, reliable data is scarce. Global Witness admitted it had to leave out many possible murders due to lack of corroborating information.

“This crisis is poorly understood, and efforts to address it woefully inadequate,” writes Global Witness. “A lack of systematic monitoring means that publicly available information relating to violence against environmental and land defenders is hard to find and even harder to verify.”

Deforestation for cattle ranching in Peru. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

But Peru’s rash of murders—which has been increasing in recent years—has yet to push the government to change. In fact, 83 percent of the murders of environmental activists were undertaken by police, the military, or private security agencies.

Nor have the murders pushed Peru recognize the land rights of its indigenous people. According to Global Witness, only 38 percent of Peruvian indigenous groups have legal tenure to their traditional lands. Currently, 20 million hectares of indigenous land waits to be processed by Peruvian authorities.

At the same time, a new law passed and signed by President Ollanta Humala in July seeks to jumpstart investment in mining and fossil fuels by slashing environmental protections. The law reduces environmental fines in many instances, forces environmental impact statements to be completed in just 45 days, and will allow fossil fuel exploitation in any newly established protected area. The law was blasted by over 100 local and international environmental groups.

“Unfortunately, the passing of law 30230 by Peru’s Congress in July 2014 raises serious doubts over the country’s willingness to [grant legal tenure to indigenous people],” reads Global Witness’ report. “The law grants extended land use rights to investors for the expansion of large-scale agriculture, mining, logging and infrastructure projects.”

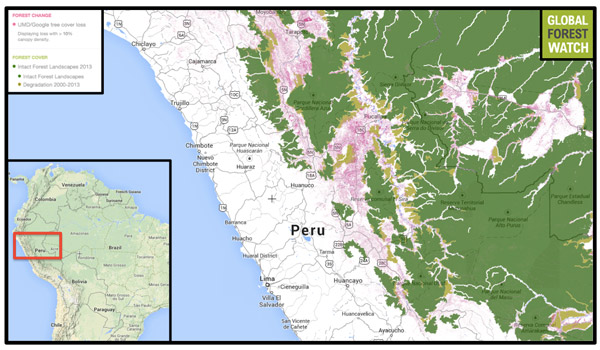

Deforestation (in pink) across northern and central Peru from 2001-2012. From Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Still, just a few months after the passage of the controversial law, Peru announced a major agreement with Norway and Germany to make the Amazonian country carbon neutral when it comes to deforestation and agriculture by 2021. Meeting such a goal would require a massive decrease in current deforestation rates. Between 2001 and 2012, Peru lost 1.5 million hectares of forest—an area larger than Connecticut—according to Global Forest Watch. Moreover, deforestation has been on the rise: in 2012 the country lost 246,130 hectares, the largest amount in the dozen years monitored.

As a part of the agreement, which would see Norway pay $300 million for proven results, Peru has pledged to grant five million hectares of land title to indigenous groups and incorporate two million hectares of indigenous land into conservation payment programs.

Yet this agreement appears to fly in the face of notorious law 30230, which begs the question: is Peru trying to have its cake and eat it too? Is the agreement with Norway and Germany merely a way to deflect criticism ahead of hosting the UN Climate Summit? Or is Peru truly serious about forest protection?

If Peru is in earnest, then Global Witness says the best way to protect forests is to end the ambiguity around land ownership.

“The realization of indigenous land rights has proven to be one of the most effective ways to curb deforestation, but communities are not receiving the support and protections they need,” reads the report.

Graph showing responsibility for activist murders. Image courtesy of Global Witness.

The organization recommends that Peru process indigenous claims for the full 20 million hectares (and not just the five listed in the Germany-Norway agreement), investigate possible links between illegal loggers and miners and public officials, provide more resources to agencies tackling illegal logging and mining, and revoke law 30230 as well as another law that allows security forces to use force against peaceful protestors.

“Peru’s credibility as a forest protector hinges upon providing land and resource rights to the country’s indigenous and rural populations,” said David Salisbury, a geography and environment professor at the University of Richmond professor who has spent time in Chota’s community. “If you want to keep forests standing, you have to invest in people who live in them, as they have the most at stake in the sustainable development of those areas…The government should recognize there are people in the forests, and give them rights to them.”

Compared to many countries, Peru still has impressive forest cover: more than 77 million hectares, covering around 60 percent of the country, according to Global Forest Watch. The country also has a wealth of cultural and indigenous diversity—including some 300,000 indigenous people. Many of these tribes have spent decades, even centuries, fighting for their forests.

Unidentified beetle in Peru. The Amazon nation is home to some of the most biodiverse forests in the world. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

A wealth of scientific research has found that among the best ways to keep forests standing is to grant legal title to the indigenous people who live in them and allow local management.

Salisbury put it this way: “How can you maintain standing forest, and mitigate climate change, if the defenders of the forest are being assassinated?”

Related articles

(09/17/2014) Peruvian authorities have pulled more human remains from a remote river in the Amazon, which may belong to one of the four murdered Ashaninka natives killed on September 1st. It is believed the four Ashaninka men, including renowned leader Edwin Chota Valera, were assassinated for speaking up against illegal logging on their traditional lands.

4 Ashaninka tribesmen killed by loggers in Peru

(09/08/2014) One of those killed was Edwin Chota, the leader of the Alto Tamaya-Saweto indigenous community who won fame for fighting illegal loggers. As such, Chota was a top target for assassination, according to a conservationist familiar with the situation.

Turning point for Peru’s forests? Norway and Germany put muscle and money behind ambitious agreement

(09/24/2014) From the Andes to the Amazon, Peru houses some of the world’s most spectacular forests. Proud and culturally-diverse indigenous tribes inhabit the interiors of the Peruvian Amazon, including some that have chosen little contact with the outside world. And even as scientists have identified tens-of-thousands of species that make their homes from the leaf litter to the canopy.

Local people are not the enemy: real conservation from the frontlines

(11/12/2014) Saving one of the world’s most endangered primates means re-thinking conservation. When Noga Shanee and her colleagues first arrived in Northeastern Peru on a research trip to study the yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda), she was shocked by what she observed.

Peru has massive opportunity to avoid emissions from deforestation

(11/10/2014) Nearly a billion tons of carbon in Peru’s rainforests is at risk from logging, infrastructure projects, and oil and gas extraction, yet opportunities remain to conserve massive amounts of forest in indigenous territories, parks, and unprotected areas, finds a study published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

How do we save the world’s vanishing old-growth forests?

(08/26/2014) There’s nothing in the world like a primary forest, which has never been industrially logged or cleared by humans. They are often described as cathedral-like, due to pillar-like trees and carpet-like undergrowth. Yet, the world’s primary forests—also known as old-growth forests—are falling every year, and policy-makers are not doing enough to stop it.

A paradise being lost: Peru’s most important forests felled for timber, crops, roads, mining

(08/12/2014) In 1988, when British environmentalist Norman Myers first described the concept of a “biodiversity hotspot,” he could have been painting a picture of the highly threatened Peruvian Andes mountain range. Today, the Andes are an immediate and looming portent of the fate of the Peruvian Amazon rainforest.

Stunning high-resolution map reveals secrets of Peru’s forests

(07/30/2014) Peru’s landmass has just been mapped like never before, revealing important insights about the country’s forests that could help it unlock the value healthy and productive ecosystems afford humanity.

Peruvian oil spill sparks concern in indigenous rainforest community

(07/29/2014) A ruptured pipeline that spilled tens of thousands of gallons of crude oil into the Marañón River in late June is fueling concerns about potential health impacts for a small indigenous community.