Lorinda in Sabi Sands.

Daily, we read or hear of more rhino being poached to satisfy the seemingly insatiable demand from Asia for rhino horn.

With countless articles and papers having been published on the subject – and the Internet abuzz with forums, including heated debates concerning possible solutions – current approaches seem to be failing. Evidence is in the numbers. Known poaching deaths in South Africa have risen sharply over the past three years: 668 rhinos in 2012, 1,004 last year, and 899 through the first nine months of 2014. This toll includes only documented kills — the real number is higher.

All the rhino in the world cannot supply the surging and ever-growing market. Presently the greatest threat to rhinos stems from a small, but carefully organized lobby of people who create a market for horn, and whose aim is to increase the demand for it.

With very little political will being demonstrated in South Africa to curb poaching — for example South Africa National Parks (SANparks) has failed to attend to a substantial list of measures recommended by conservationists, including better utilization of sniffer dogs and relocation of villages next to the eastern border of the Kruger National Park — the situation appears increasingly bleak.

White rhino in South Africa. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

One ‘solution’ which is being implemented in various countries, but one is little more than a smokescreen for pro-traders aiming to secure more supply, is de-horning. Simply put, de-horning does not work: buyers seek the softer, more porous outer layers of horn as well as the base, meaning that de-horned rhinos are still a target for poachers, who hack out that base. In addition, de-horning fails to protect rhinos from poachers who shoot them purely to avoid wasting time tracking them again. Furthermore, de-horned rhinos are at a disadvantage in the wild. Rhinos without horns cannot protect their young from predators such as hyenas, and are unable to push aside stones, wood or branches to access better quality food.

Taking all this into account, a small group of people in South Africa formed the Rhino Rescue Project, the aim of which is to provide a sustainable, low-cost and proactive solution to the chaotic rhino poaching crisis in South Africa. During an October 2014 interview, Rhino Rescue Project spokeswoman Lorinda Hern talked about the group’s work.

Lorinda in South Africa. Photo by Miona Janeke.

AN INTERVIEW WITH LORINDA HERN

Derek Schuurman: As founder of the Rhino Rescue Project, could you tell us about your work; about the project, and what inspired you to create this initiative?

Lorinda Hern: It was the poaching of one of our own animals in 2010 that prompted me to take an interest in the growing poaching crisis, and to apply my mind to possible ways in which the threat of repeated attacks could be addressed. We considered a number of alternatives at the time, but found most of them to be reactive (in other words, they would not deter poachers from targeting our animals again.) It was clear to us that we needed to look at the problem with fresh eyes in order to devise potential proactive alternatives. In the broadest and most simple terms, we wanted to make our animals less attractive targets to poachers, and so the idea of possibly contaminating their horns as a means to accomplish this began to crystallize. (If the animal’s horn is perceived to be worthless by would-be poachers, it would stand to reason that it may be worth the poacher’s while to target other animals instead). It is true that this would essentially shift the poaching problem elsewhere, but the same could be said of all other poaching interventions as well.

The horn material inside a treated horn is a bright pink color. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: Given the alarming statistics of rhino deaths archived thus far in 2014,it is clear that many ‘solutions’ thus far proposed and/or tried to combat poaching of rhinos are just not working. What’s your approach?

Lorinda Hern: We certainly do not believe that there is a proverbial “silver bullet” solution that can ever eradicate poaching in its entirety. For this reason, we would not recommend that interventions be implemented on a “mutually exclusive” basis and/or in isolation. If anything, as many security measures as is practical and possible should be implemented to ensure the ongoing safety of rhinos in South Africa and elsewhere. All security measures have strengths and shortcomings – the ideal is to implement measures that can “dovetail” with each other so that collective strengths are maximized and shortcomings are offset. Horn devaluation, by means of infusion or other methods is, at best, an interim measure to keep animals alive in real time, and should be viewed as such – not as a long-term solution to poaching.

Two holes are drilled into each horn for the probes to the infusion device and microchips to be inserted. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: On your Facebook page you describe the chemical compound which is being used at this stage, as a cocktail of drugs which are administered in a quantity so as to ensure the animal remains unharmed, but which upon ingestion by humans, is severely toxic. Could you please elaborate on how this is done? And does the animal’s horn need to be re-infused every 3 – 4 years?

Lorinda Hern: A full horn growth cycle spans four years approximately. Thereafter, treatment would have to be re-administered, should the rhino owner deem it necessary. However, it was always our hope that, with infusion, we might buy these animals some much needed time until CITES and other governing bodies devise more sustainable long-term solutions, eventually rendering treatment unnecessary. We took great care in selecting compounds developed and registered specifically for use on animals (thus ensuring that no possible harm could come to the rhino itself) but that are, as is the case with all commercially available pesticides, inadvisable for humans to handle or consume.

The back horn is saturated with the treatment compounds as the infusion device forces the liquids into the horn tissue under pressure. Caption and image courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: Besides acting as a potential deterrent against poaching, are there other reasons to infuse the horns of rhinos?

Lorinda Hern: Rhino Rescue Project’s wildlife veterinarian, Dr. Charles van Niekerk had started some time ago to research the possibility of depositing ectoparasiticides (chemicals used to control pests) inside rhino horns because so many of these animals in captive populations suffer from uncomfortably heavy tick loads. It was from this initial research that the idea to do the same (with some modifications) as an anti-poaching measure took shape. It is also the reason we still utilize ectroparasiticides instead of harsher chemicals that could potentially be harmful to the animals. Needless to say, however, ectoparasiticides are toxic and consumption by humans therefore, ill-advised.

When the animal is sedated, its ears are plugged and eyes covered to reduce stress. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: Does infusion allow tracking of horns? For example, would it enable detection via an airport scanner?

Lorinda Hern: Our experimentation into viable horn devaluation methods over the past four years has enabled Rhino Rescue Project to make a number of exciting changes and improvements to our process. I say “exciting” because there is so little existing research material available on rhinos and, hence, everything we test potentially presents us with an opportunity to contribute greatly to the global body of knowledge on these animals. In this way, we are constantly modifying our infusion compounds and coloring agents. The ideal would be to find a pigment that is x-ray detectable but also long-lasting enough to render horns useless for ornamental use.

Derek Schuurman: In addition to the chemical infusion and the dye, you also work in conjunction with scientists at Onderstepoort who have made available a DNA sampling kit for a national database of treated animals. No doubt this will assist the legal community in prosecution cases where animals with treated horns have been poached. In terms of cost effectiveness and commercial viability, how do your methods compare with other proposed solutions like as de-horning

Lorinda Hern: RRP has always aimed to render a service that is affordable enough for more rhino owners to make use of it. As such, the entire process (which includes the actual devaluation procedure, DNA sampling and storage, pregnancy testing, microchipping and insurance) is priced roughly the same as an average dehorning procedure. As has been said before, devaluation is by no means a “cure all”, nor have we stumbled upon a perfect methodology, but based on marked reductions in poachings and/or incursions on properties where treatments have been done, the concept undoubtedly has merit and could well play an important role is preserving rhinos for future generations.

Rhino after the procedure. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: What at present are your primary challenges?

Lorinda Hern: Sadly, because of the vast sums of money at stake, rhino poaching has become a highly contentious and political issue. Fragmentation within the industry is detrimental to almost all anti-poaching initiatives. Nowhere has this been more visible than the way in which our efforts have been criticized and undermined by those one would have expected the strongest support from. We, as private individuals, face challenges in terms of legalities that preclude us from performing our research into improved devaluation techniques. Very little existing research on rhino anatomy exists, which obviously makes any new research not only valuable, but fairly difficult.

Derek Schuurman: Approximately how many rhino have you managed to treat to date?

Lorinda Hern: We have treated roughly 280 animals to date, over the course of the past four years. Of these, seven animals have since been reported to us as having been lost (as a result of poaching and/or natural mortality). This amounts to less than two animals lost per year – a triumph by any standard.

Lorinda on the right. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: In South Africa, how do you perceive support for the initiative? Is there much criticism?

Lorinda Hern: Although there has been much public support for our work, there has been strong opposition of our efforts by the so-called “pro-trade” camp. This state of affairs is incredibly sad, as it is the animals that bear the brunt of it in the long run. Although one can certainly understand why some would push aggressively for the legalized trade in rhino horn based on the potential profits that could be generated from horn sales, all rhino owners are not interested in essentially becoming commercial farmers, and these rhino owners right to secure their animals in different ways (of which horn devaluation is but one) should also be respected. Instead, we have been accused of trying to “kill the market” and “tarnishing the reputation of South African rhino horn in the minds of consumers” – neither of which has ever been our goal.

Lorinda Hern and team at a horn infusion. Courtesy of the Rhino Rescue Project

Derek Schuurman: How can the international community assist your initiative?

Lorinda Hern: Although RRP is a service provider, not yet another rhino “charity”, we have identified a number of state-owned properties on which horn devaluation procedures could play a valuable role in protecting rhino populations from poachers, but where funding to the perform the procedures is limited (if not non-existent). So if members of the international community wish to sponsor these efforts, such donations are always much appreciated. We welcome donors to attend the procedures if at all possible and encourage them to become actively involved with the treatment process. In fact, this is true for all anti-poaching initiatives: only support those where you are 100% sure how your funds will be utilized towards rhino conservation. Funding, however, is less important than awareness about the plight of the rhino, and it this, the international community can be invaluable.

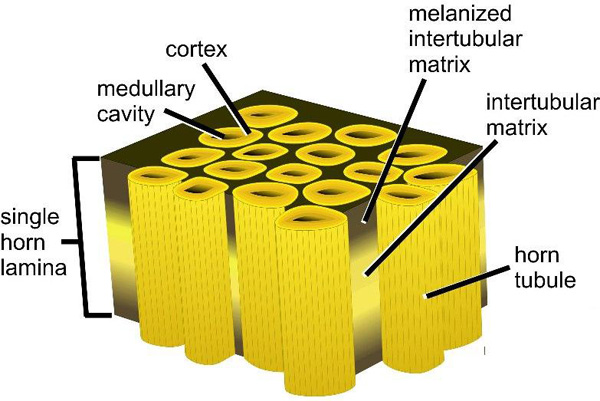

Diagram showing the internal structure of rhino horn. Courtesy of Hieronymus, Tobin L., Lawrence M. Witmer, and Ryan C. Ridgely. 2006. Structure of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) horn investigated by x-ray computed tomography and histology with implication for growth and external form. Journal of Morphology 267(10)1172–1176.