Peat forest clearing for oil palm in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler

The Indonesian province of Central Kalimantan is moving forward on an oil palm plantation monitoring system it hopes will help meet a commitment to reduce deforestation 80 percent by 2020.

The online monitoring system will include “information on the performance of plantation concessions such as productivity, the number of smallholder farmers, deforestation and other land cover change, and fire occurrence,” according to Earth Innovation Institute which designed and is helping the provincial government implement the system.

Four districts — Kotawaringin Barat, Kapuas, Pulang Pisau, and Gunung Mas — will pilot the system, which will offer governments and the public unprecedented insight into palm oil production at the local level.

“This system will enable local governments to detect non-compliance and also to acknowledge voluntary initiatives of companies in meeting sustainability criteria,” said Earth Innovation Institute. “Through the system, the government will be able to identify degraded lands that can be allocated for future plantation licenses. The system can also trace where oil palm is planted, harvested, processed and sold.”

Forest clearing for oil palm in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett Butler

The province is also launching an effort to boost smallholder production using more sustainable approaches. That initiative focuses on increasing productivity of small operations, which typically have much lower yields than company-run plantations, resulting in more expansive land requirements.

Both projects come under Central Kalimantan’s roadmap to low-deforestation development and sustainable palm oil production, which includes a commitment to cut deforestation 80 percent from the 2006-2009 average by 2020. The plan also endeavors to increase smallholder palm oil output from 11 percent of the sector to 20 percent.

The goal of the roadmap is to eventually establish Central Kalimantan as a “safe” source for palm oil. The reasoning: if all producers in the province are compliant with environmental standards, then buyers could have confidence that any palm oil sourced from Central Kalimantan was produced responsibly.

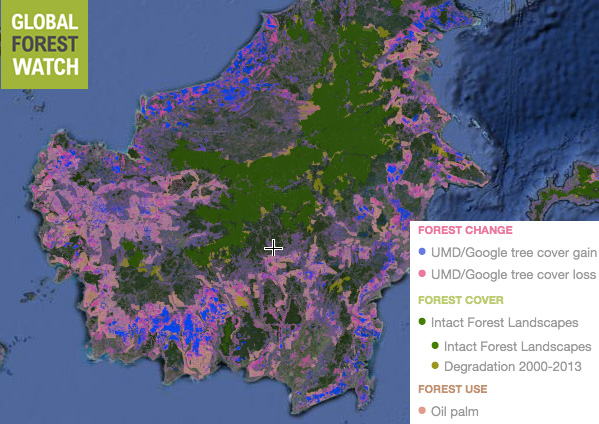

According to Global Forest Watch, Central Kalimantan lost more than 2 million hectares of forest cover between 2000 and 2012. Most of the province’s lowland forests have been logged for timber, cleared, or converted for oil palm plantations.

However the sector still has a long way to go before meeting that objective. Destruction of peatlands and rainforests is still rampant across Central Kalimantan. Illegal plantations are widespread — a recent assessment found 42 companies are presently operating without proper licenses.

There are several major challenges that need to be overcome to move the province — and Indonesia as a whole — toward less damaging palm oil production. To start, neither the government nor the private sector has a good idea of what land is allocated for what use. Overlapping permits and conflicting spatial plans mean that multiple parties may have justifiable claims for a single piece of land. Straightening out those claims is the primary goal of the “One Map” process that aims to harmonize permits and land use across all ministries for Indonesia’s land mass. But that effort is expected to take the better part of a decade. Central Kalimantan hopes to do that on a smaller scale.

Much of Central Kalimantan’s land has been allocated for oil palm plantations, logging concessions, and mining as shown in these Global Forest Watch maps.

Another problem is that when companies try to preserve forest areas within their concessions, there is no legal mechanism for doing so. Situations have arisen where local officials have tried to seize these forest reserves set aside by responsible firms and turn them over to companies or communities that have no qualms about chopping them down.

Finally there is presently little incentive for palm growers — especially smallholders to medium-sized companies — to clean up their operations. That might change with recent zero deforestation commitments from giant palm oil producers and traders like Golden-Agri Resources, Wilmar, and Cargill, but for now there are few rewards for operators who go through the expense of getting certified.

Working with the government, Earth Innovation Institute has laid out a series of recommendations to try to address these issues, including the monitoring and smallholder initiatives. These could help push new oil palm development away from forests and peatlands toward degraded, low-carbon lands, while increasing overall palm oil production. By 2020 these programs, if fully implemented, could avoid 1.2 million hectares of deforestation and more than 600,000 tons of carbon emissions, while reducing poverty amount native Dayak communities.

But success won’t happen unless producers are on board, according to Hon Teras Narang, the Governor of Central Kalimantan.

“The Government of Central Kalimantan cannot achieve sustainable palm oil production by itself,” the governor said in a statement. “We need to work together with companies operating in the Province.”