Recent deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Photo by Alexander Lees of the Goeldi Museum.

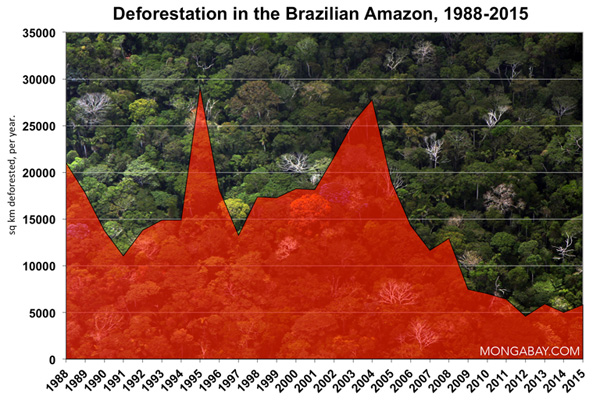

Smallholder properties account for a rising proportion of overall deforestation in Brazilian Amazon, suggesting that Brazil’s progress in cutting forest loss through stricter law enforcement may be nearing the limits of its effectiveness, finds a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research, led by Javier Godar of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), split properties into four classes — very large holdings (greater than 2,500 ha), large (500-2,500 ha), medium (100-500 ha), and small (less than 100 ha) — and looked at the contribution of each class to overall deforestation between 2004 and 2011, a period when annual deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon plunged by nearly 80 percent. It found that very large properties accounted for a decreasing share of forest loss in the region.

“Since 2004 the contribution to total annual deforestation by large properties has fallen by two-thirds, while the contribution of smallholders has increased by a similar amount,” the authors told mongabay.com.

Deforested landscape in Alta Floresta. Photo by Alexander Lees.

The research also found that forests surviving within smallholder blocks tend to be in better shape and less fragmented than those in large and very large holdings. The authors say this is likely a product of large landowners exploiting these forests for timber, an activity allowed within “legal reserves” on private land.

“Wealthier landowners are more able to access and exploit their forests for timber,” said Toby Gardner, a co-author and also a research fellow at SEI, in a statement. “[This] underscores the vital need for incentives to be given to improve the condition of remaining forests.”

“At the moment there continues to be no legal incentive to maintain or improve the condition of remaining areas of forest,” the authors added. “Yet a forest degraded by unsustainable logging and fire provides only a small fraction of the conservation and ecosystem service benefits provided by an old-growth, relatively undisturbed area of forest.”

Agricultural frontier in Santarem, Brazil. Despite the increasing proportion of deforestation resulting from smallholder properties, the majority of deforestation is still associated with larger properties in the Brazilian Amazon. Photo by Toby Gardner

Additionally, the study reported a shift in where deforestation is occurring. A greater proportion of clearing is now occurring in remote areas with weaker governance and accordingly, no data on land holding size. These areas account for nearly 40 percent of all the Brazilian Amazon’s remaining forests.

|

Impact of the new Forest Code?

In 2012 Brazil revised the Forest Code, which governs land use in the Amazon and other ecosystems. Some environmentalists complained that the change would spur increased deforestation. Others weren’t so sure, asserting that landowners would be more likely to comply with new regulations, thereby benefitting forests. What does the new study show? In short, nothing to answer that question. The new study looked only at the period before the new Forest Code was adopted. But the authors are certainly interested in the question, noting that compliance will be most difficult for smallholders to achieve. “The original forest code was widely recognized as being dysfunctional in many important aspects, with the majority of farmers in the Amazon region being outside the law in some way. This suggests that the underlying drivers of deforestation are not, fundamentally, a legal issue – but an economic, institutional and cultural challenge,” the authors told Mongabay. “Achieving compliance will be hardest for the smallholder farmers, who – despite being exempt from many aspects of the new forest code – often depend upon fallow agriculture and small-scale deforestation to maintain their livelihoods.” |

The results suggest that Brazil may be reaching the limits of its current strategies for reducing deforestation, which have primarily focused on law enforcement enabled by monitoring programs, including a monthly satellite-based deforestation detection system run by INPE, the national space agency. That system detects forest loss in blocks greater than 25 hectares. Clearing on a smaller scale might evade detection.

There has been speculation that some large operators may be using that blind-spot to their advantage, outsourcing their clearing to smallholders. The authors said their work doesn’t rule out that possibility.

“It is possible that larger property owners have adapted their behavior to the clearance of smaller, incremental patches within the detection limits of the DETER system. Such a shift could perhaps also help explain the significantly higher levels of forest degradation in areas dominated by larger landholdings,” the authors told Mongabay. “If small patches of deforestation are actually being picked up as degradation by the DEGRAD system (and not being classified as deforestation). Testing this hypothesis would require more detailed analyses based on higher-resolution remote-sensing data that is urgently needed.”

Beyond better data, the authors say that sustainable development programs and other incentives are needed to consolidate gains in curbing deforestation, especially among smallholders.

“Further reductions in deforestation in the Amazon are challenging both because deforestation is happening in more, smaller, and remoter areas and is therefore harder to detect and more expensive to control,” Godar said. “New approaches are needed, particularly to engage smallholders more. Targeting them with the same punitive measures used for large landowners, when they have far fewer resources, would be too costly and arguably not socially or politically acceptable. They hold more forested areas and their forests are on average in better condition, so it is important to help them preserve those forests, rather than point the finger at them.”

That change in approach promises to be more costly than law enforcement targeted at a relatively small number of large landowners whose operations are visible to satellites and tend sell to companies with greater exposure to market pressures for products produced without deforestation.

“Preserving remaining rainforests and promoting sustainable rural development will require complementing traditional enforcement-based approaches with incentive measures,” said study co-author Pablo Pacheco, a scientist at the Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). “We need to take into account the socioeconomic difficulties facing many smallholder farmers, and work to alleviate rural poverty and foster sustainable development along with reducing deforestation.”

[top] Actor dominance by census tract in the Brazilian Legal Amazon (BLA). The white dashed polygons correspond to municipalities under prioritization and increased monitoring included in the federal government Critical Municipalities List. Only 14.4% of the total deforestation and 30.1% of the total area was not accounted for in terms of actor dominance. [bottom] Annual deforestation and degradation dynamics per type of actor in

the BLA. (A) Annual rate of deforestation change. (B) Percentage share of

annual deforestation. (C) Percentage share of annual deforestation relative

to 2004 (baseline year). (D) Percentage forest degradation per hectare of

forest. (E) Percentage share of annual degradation. (F) Percentage degradation

share relative to 2007 (baseline year). Images and caption courtesy of the authors.

CITATION: Godar, J., Gardner, T.A., Tizado, E.J., Pacheco, P. (2014) Actor-specific contributions to the deforestation slowdown in the Brazilian Amazon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. October 17, 2014.