Indonesian island lost nearly one million hectares of forest over 12 years

For 10 million years the Indonesian island of Sulawesi has been disconnected from other landforms, almost inviting evolution to color outside the lines. Despite a growing population and limited space — more than 17 million people reside on the island as of 2010 — Sulawesi has managed to provide a safe haven to hundreds of unique species as they evolved over millennia.

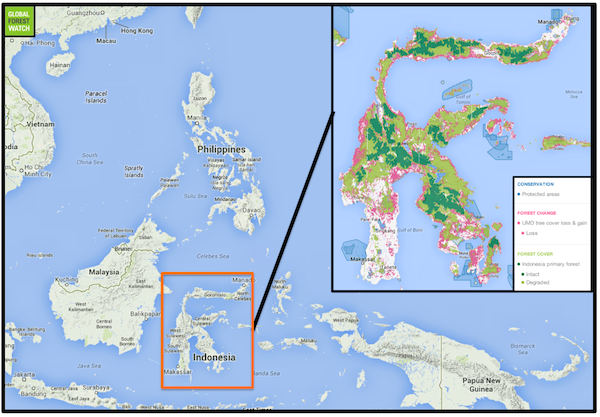

But that haven may soon be lost to uncontrolled extraction of forest products from Sulawesi’s many pristine ecosystems. According to data from Global Forest Watch, Sulawesi lost more than 950,000 hectares of forest between 2001 and 2013, representing about 5 percent of its area — which may spell danger, particularly for species endemic to the island that exist nowhere else in the world.

More than 550 species of butterflies have been catalogued on Sulawesi, of which more than 300 are endemic. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Sulawesi’s 17.4 million hectares comprise 14 different kinds of ecosystems including mangroves, rainforests, lowland forests, caves, montane forests, marine parks. There are even expanses of hot sand near volcanoes that are used for nesting sites by the Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo) – a bird species that exists solely on Sulawesi and which is listed by the IUCN as Endangered due in part to habitat loss.

Currently, Indonesia harbors more threatened species than any other nation in the world. Over 60 percent of mammals and more than one-third of Sulawesi’s birds are endemic. But Indonesia’s other world record only adds to those woes. Its rate of deforestation is the highest in the world, even outdoing Brazil.

Satellite data from Global Forest Watch shows that logging, mining, oil palm plantations and conversion of land for agriculture are driving deforestation in Sulawesi. Over 80 percent of the island’s forests are degraded to some extent, particularly in the lowland areas and in its mangrove areas. Experts say less than 5 percent of Sulawesi’s mangroves and lowland forests remain undisturbed, while 99 percent of its wetlands are either damaged or destroyed.

Sulawesi lost nearly a million hectares of forest between 2001 and 2013, and large tracts of its remaining primary forest were unprotected as of 2000. Click to enlarge.

Much of Sulawesi’s forest loss is due to logging and plantation development. Click to enlarge.

With an upcoming election and a possible change in government, it remains to be seen whether Indonesia will uphold its current moratorium on deforestation aimed at curbing emissions. This is especially of concern now as Indonesia recently announced its plans to continue using “degraded” forests for industrial purposes like oil palm plantations.

Because most of Sulawesi’s pristine lowland forests had been lost nearly two decades ago, its rate of deforestation doesn’t seem too high compared to the rest of Indonesia. In reality however, should the present rate of forest loss continue, it would be nothing short of catastrophic for the island’s remaining wildlife.

In June 2014, a team of scientists discovered a new carnivorous water rat which is literally one of a kind because it represents an entirely new genus. Dr. Kevin Rowe, Senior Curator of Mammals at Museum Victoria, was on the team that made this new discovery.

“My first trip to Sulawesi in 2010, we headed to a site on the southeast peninsula where, in 2007, my herpetology colleague had observed healthy lowland forest, home to the Sulawesi Dwarf Hornbill,” Rowe told mongabay.com.

“When we arrived just three years later, the forest was gone. All that was left was a river of silt draining into the coastal mangroves and a small city of tin roofs not yet rusted. The wildlife was gone and what livelihood was left for the local people could only be imagined. My colleague who had witnessed the healthy forest, wept.”

A critically endangered crested black macaque (Macaca nigra) took a photo of itself using equipment owned and set up by David Slater. |

Lowland rainforests, Rowe says, are the worst hit by deforestation.

Data mapped by Global Forest Watch shows rampant logging even in protected areas, potentially signaling illegal clearing of the few remaining stretches of intact forests.

Critical strongholds of wildlife like the Bogani Nani Wartabone National Park in northern Sulawesi and the Lore Lindu National Park in central Sulawesi are being threatened by logging, illegal mining for gold and nickel, and development of oil palm plantations on the periphery.

Deforestation has undoubtedly affected the already limited habitat of some of Sulawesi’s iconic endemic mammals like the Babirusa (Babyrousa babyrussa) or pig-deer, the endangered lowland Anoa (Bubalus depressicornis), the spectral tarsier (Tarsius tarsier) and the critically endangered crested black macaque (Macaca nigra), a species recently in the news for clicking some stunning “selfies” that are now at the center of a copyright argument.

The future of Sulawesi’s endemic birds is also uncertain. Loss of forests is disturbing the knobbed hornbill (Rhyticeros cassidix), the critically endangered Siau scops owl (Otus manadensis siaoensis) and the endangered Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo).

There are many other species that may be affected by deforestation, but the true extent of its impact is shrouded by lack of research.

“On Sulawesi we may not know what it means for wildlife, in part, because our knowledge of the diversity, distribution, and abundance of wildlife on Sulawesi is so limited,” Rowe said.

But while some of the world’s rarest species are struggling to survive, new species like the carnivorous water rat are still being discovered. Although this is a good sign, it is a race against time.

“Our understanding of the species diversity, even in mammals, is woefully underestimated for Sulawesi,” Rowe said. “Many species are known from a single specimen or a single locality, and therefore, we cannot effectively assess geographic distributions, population size and threats.”

“Many species remain to be discovered and described. We need to improve our understanding of biodiversity so that resource extraction – an essential part of the livelihood of the Sulawesi people – can occur more judiciously with recognition of where the most critical habitat remains,” he said.

A tarsier of genus Tarsius, many species of which are threatened with extinction. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

“The greatest threat,” Rowe said, “is that we continue to extract; essentially blind to the impacts on Sulawesi’s remarkable and unique wildlife.”

However, not all human communities on Sulawesi are wantonly clearing the island’s forests.

“For generations, the Mamasan people have restricted clearing (land) for plantations and rice fields to areas below 1500 meters,” Rowe said. In particular, preservation of forests on the high plateau of Mount Gandangdewata by the Mamasans has been the most important local conservation initiative Rowe has witnessed, as they are some of the most intact forests on Sulawesi where two new genera were discovered.

These forests currently have no government protection, and Rowe recommends that any efforts to protect them formally should involve and recognize the Mamasan people for their deep knowledge of and cultural connection to them.

“They are the ideal caretakers for this land that they have nurtured and valued for generations.”

Rowe also points to evidence demonstrating the importance of reserves, especially those that include local people in forest protection.

“The National Parks of Sulawesi contain some of the most pristine forest and greatest diversity,” he said. “We should not undervalue their protective role.”

Citations:

- Bell, L. (2014, Feb 19). Uprising against illegal mining in Indonesia pits villagers against miners, police. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2014/0219-lbell-bangka-island-mine-protest.html

- Butler, R. A. (2014, June 12). Despite green pledge, Wilmar partner continues to destroy forest for palm oil. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2014/0612-greenomics-kencana-agri-palm-oil.html

- Butler, R. A. and Hance, J. L. (2010, Dec 06) Saving the maleo, a geothermal nesting bird, in Sulawesi. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2010/1206_summers_maleo_hance_interview.html

- Butler, R. A. (2007, June 28) Rare and mysterious forests of Sulawesi 80% gone. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2007/0628-sulawesi.html

- Erickson-Davis, M. (2014, June 19). Scientists discover carnivorous water rat in Indonesia, good example of convergent evolution. Mongabay.com. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2014/0619-morgan-water-rat.html

}}

Related articles

Indonesia to hear indigenous peoples’ grievances on land disputes

(08/22/2014) Public hearings into alleged violations of indigenous peoples’ land rights will open next week in Palu on the island of Sulawesi. This is the beginning of a series of hearings by the Commission on Human Rights to explore conflicts affecting indigenous people in forest areas. The Commission will travel throughout Indonesia, providing concerned parties an opportunity to meet and discuss land disputes, before submitting the results of their findings to the next president.

A tale of two fish: cyanide fishing and foreign bosses off Sulawesi’s coast (Part I)

(07/08/2014) In spring and summer, after the monsoon storms have passed, the fishing boats set out again from tiny Kodingareng Island in the Spermonde Archipelago off the coast of South Sulawesi. In the afternoon heat, Abdul Wahid joins his fellow fishermen in the narrow shade of the beachfront village houses to check out the daily fish prices.

Scientists discover carnivorous water rat in Indonesia, good example of convergent evolution

(06/19/2014) Researchers have discovered a new carnivorous water rat on the island of Sulawesi that’s so unique it represents an entirely new genus. They believe many more new rodent species await discovery in this relatively undisturbed part of Indonesia, but mining and other types of development may threaten vital habitat before it’s even surveyed.

Despite green pledge, Wilmar partner continues to destroy forest for palm oil

(06/12/2014) Two palm oil companies partially owned by Wilmar are continuing to destroy rainforests in Indonesia despite a high profile zero deforestation pledge, alleges a new report published by Greenomics.

Mining company attacks scuba diving tourists in Indonesia

(06/05/2014) Conflict from mining activities on Bangka Island off North Sulawesi, entered a new chapter after a local resort manager voiced concern over an incident involving its clients and mining staff last Saturday.

Colorful bird on remote Indonesian islands should be classified as distinct species, say scientists

(06/04/2014) A colorful bird found on the Wakatobi islands south of Sulawesi in Indonesia is sufficiently distinct from birds in nearby areas to be classified as a unique species, argue scientists writing in the current issue of the open-access journal PLoS ONE.

Uprising against illegal mining in Indonesia pits villagers against miners, police

(02/19/2014) Hundreds of villagers and fishermen on Bangka Island in North Sulawesi attempted to stop a ship owned by PT Mikgro Metal Perdana (MMP) from offloading heavy machinery to be used in mining operations. The Indonesian Supreme Court ruled in November that the company’s mining permits, issued by the local government, should be invalidated.

Indonesia rejects, delays 1.3m ha of concessions due to moratorium

(02/12/2014) The Indonesian government has rejected nearly 932,000 hectares (2.3 million acres) of oil palm, timber, and logging concessions due to its moratorium on new permits across millions of hectares of peatlands and rainforests, reports Mongabay-Indonesia.

Mining in Indonesia taking a heavy social, environmental toll

(06/03/2013) In a patch of rainforest in northern Sumatra, a 28-year-old in jeans and tall rubber boots snubs out his cigarette and pulls a headlamp over his short black hair. Standing under a tarp, he flicks the light on and leans over the entrance of a narrow shaft lined with wooden planks that he and other miners cut from trees that once stood here. He gives a sharp tug on a rope that dangles 100 meters, plateauing in sections, and slides down. For hours, the man, Sarial, will use a pick to scrape away and bag rocks that are hauled to the surface by another miner, using a wooden wheel.

- Butler, R. A. (2014, June 12). Despite green pledge, Wilmar partner continues to destroy forest for palm oil. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2014/0612-greenomics-kencana-agri-palm-oil.html