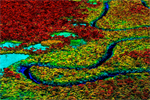

Iselle damage in Hawaii. Photo by Greg Asner

Damage from Hurricane Iselle, which recently battered Hawaii’s Big Island, was exacerbated by invasion of non-native tree species, say experts who have studied the transformation of Hawaii’s native forests.

Iselle, which made landfall on the Big Island on August 7, was the third-strongest tropical cyclone to hit Hawaii since 1950. It caused upwards of $50 million in damage, mostly from lost fruit harvest and impacts on infrastructure and housing. Much of the damage was caused by downed trees, many of which were invasive albizia and ironwood that have overtaken natives in Hawaii’s forest landscape.

The invasion of non-native tree species has long been a concern to ecologists, who fear the impact on endemic species and ecosystems, but damage from the storm has put a spotlight on the dangers and economic costs of invasives, which are apparently more vulnerable to high winds, according to Flint Hughes of the U.S. Forest Service.

“At least 95 percent of the trees that came down and caused damage were non-native trees and the vast majority (90 percent) of those trees were Albizia (Falcataria moluccana),” Hughes told Mongabay.com. “If native forests had not been replaced by Albizia and other non-native trees, the overall damage from Iselle would have been very minor. Nearly all the damage (including ongoing widespread power outages) was due to falling 35 to 40 meter tall albizia trees.”

Greg Asner of the Carnegie Department of Global Ecology agreed.

“Without a doubt, the native forest canopy in the lowlands, which is now in the minority of forests and is highly threatened by continuing land-use change, fared far far better than the non-native forests that are now widespread in the lowlands,” Asner told Mongabay.com. “In particular, the non-native, highly-invasive albizia and ironwood trees came crashing down in huge swaths of land — really big areas where mortality is 80% or more. You see none of that with the remaining native forest stands that are dominated by the keystone Hawaiian endemic canopy tree called ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha).”

Table from Asner’s Iniki study

The problem is not new to scientists. After the hurricane Iniki devastated Kauai in 1992, Asner documented the proclivity of non-native trees to crash down during storms.

“I found that non-native trees had a 2-3 times the chance of falling down than did the native trees,” he explained. “Yet in the Hurricane Iselle case, with albizia (which was not in my surveys on Kauai in 1992), I estimate that the non-native trees had 100 times the probability of falling down compared to the native ohia trees.”

Asner is now hoping to assess damaged areas using the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), an advanced airplane-based sensor system that maps forest structure and chemistry in three dimensions at high resolution.

“I mapped the entire area with the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO) before the hurricane, and we carefully calculated the height and biomass of the forests that have now been wiped out,” he said. “We are now scrambling to find support to either refly these forests to fully assess the impact on the ecology and carbon cycle, or to acquire high-resolution satellite imagery that can easily be used to ‘subtract’ the forest cover and carbon stocks from the previously acquired CAO maps.”

A 3-D image of a Hawaiian rainforest depicts the encroachment of two invasive tree species (represented in pink and red) upon the native trees (in greens and blues). The low vegetation in the foreground is an agricultural field. Courtesy of Greg Asner / the Carnegie Department of Global Ecology

Asner hopes that quantifying the damage caused by Iselle could provide a further justification for protecting and restoring Hawaii’s native forests.

“Without a doubt, this is another blaring indication that native forest restoration needs to be a number-one priority for the State of Hawaii,” he said. “It is not a fringe nature community or ecotourism issue anymore. It is an issue that is affecting people and their safety, and it is only going to get worse until the State and the citizens of Hawaii make native forest restoration a priority. The great thing is that everyone can participate; everyone has a role to play; it doesn’t take rocket science; it takes community effort.

Hughes added that there’s no reason to further delay taking action.

“We have talking about the threats posed by Falcataria moluccana for years. One point that we make is that while we have many invasive species problems in HI, Falcataria is one that should be dealt with because it can actually Kill you. That has become obvious with Iselle.”

|

Q&A with Greg Asner Mongabay:Was there much storm damage where you live? Greg Asner: The damage where I live, up the montane forests of Kilauea, were minimal compared to the lowlands. At my house, we had several large non-native trees fall down, smashing other trees, and creating a large tangle that will take a few weeks to clear out with a crew of four. The immediate neighbor, a Hawaiian man, was not as lucky. He has several large non-native trees fall, and one massive one went right into his house. Mongabay: What type of forest is in the area? Greg Asner:I live up about about 1000 m elevation, so it is sub-montane to montane tropical forest. In the lowlands below us, the hurricane smashed massive areas of lowland forest. See below… Mongabay:Did native tree species withstand the storm better than exotics/invasives? Greg Asner:Without a doubt, the native forest canopy in the lowlands, which is now in the minority of forests and is highly threatened by continuing land-use change, fared far far better than the non-native forests that are now widespread in the lowlands. In particular, the non-native, highly-invasive albizia and ironwood trees came crashing down in huge swaths of land — really big areas where mortality is 80% or more. You see none of that with the remaining native forest stands that are dominated by the keystone Hawaiian endemic canopy tree called ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha). After hurricane Iniki destroyed much of Kauai in 1992, I went there to survey the forest damage. I found that non-native trees had a 2-3 times the chance of falling down than did the native trees. Yet in the Hurricane Iselle case, with albizia (which was not in my surveys on Kauai in 1992), I estimate that the non-native trees had 100 times the probability of falling down compared to the native ohia trees. And I am trying to be conservative here with my initial estimates. Albizia and ironwood are scourges in Hawaiian ecosystems for so many reasons that we already knew about and have written about including threatening native biodiversity and altering the carbon cycle of the region in ways that makes these forests very unstable. Now, with hurricane Iselle, we see that the damage caused by the far higher likelihood of albizia and ironwood falling down onto people, their homes, and power lines, left people stranded, without food and water, and probably years of problems ahead. This is a clear sign that the use of non-native, fast-growing, invasive trees in places like Hawaii greatly reduces ecological resistance to occasion large disturbance events like hurricanes. The citizens of the most invaded and affected areas are being handed a hard lesson that has gone mostly unheard outside of the scientific research community. I mapped the entire area with the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO) before the hurricane, and we carefully calculated the height and biomass of the forests that have now been wiped out. We are now scrambling to find support to either refly these forests to fully assess the impact on the ecology and carbon cycle, or to acquire high-resolution satellite imagery that can easily be used to “subtract” the forest cover and carbon stocks from the previously acquired CAO maps. |

Related articles

Video: Incredible technology maps rainforest biodiversity in 3D

(11/26/2013) Technology that enables scientists to catalogue a rainforest’s biodiversity in stunning detail by airplane was highlighted in a recent TED talk. Speaking at TED Global in Edinburgh, Scotland this past June, researcher Greg Asner explained the science behind his ground-breaking forest mapping platform: the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), an airplane packed with advanced chemical and optical sensors.

Researchers produce the most accurate carbon map for an entire country

(07/22/2013) Researchers working in Panama have produced the most accurate carbon map for an entire country. Using satellite imagery and extremely high-resolution Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data from airplane-based sensors, a team led by Greg Asner produced a detailed carbon map across the Central American country’s forests. The map reveals variations in forest carbon density resulting from elevation, slope, climate, vegetation type, and canopy coverage.

Breakthrough technology enables 3D mapping of rainforests, tree by tree

(10/24/2011) High above the Amazon rainforest in Peru, a team of scientists and technicians is conducting an ambitious experiment: a biological survey of a never-before-explored tract of remote and inaccessible cloud forest. They are doing so using an advanced system that enables them to map the three-dimensional physical structure of the forest as well as its chemical and optical properties. The scientists hope to determine not only what species may lie below but also how the ecosystem is responding to last year’s drought—the worst ever recorded in the Amazon—as well as help Peru develop a better mechanism for monitoring deforestation and degradation.