Peru lost nearly a quarter-million hectares of forest in 2012

In 1988, when British environmentalist Norman Myers first described the concept of a “biodiversity hotspot” – an area with at least 0.5 percent or 1,500 endemic plants that has lost 70 percent of its primary vegetation – he could have been painting a picture of the highly threatened Peruvian Andes mountain range. Today, the Andes are an immediate and looming portent of the fate of the Peruvian Amazon rainforest.

This year, Peru scored a 45.05 on the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), coming in 110th in the world. The EPI is a metric that analyses the performance of a country with respect to high-priority environmental issues, mainly the protection of human health from environmental harm and the protection of ecosystems themselves.

Conservation biodiversity hotspots in South America. Data from a 2011 assessment by Conservation International accessed via the Global Forest Watch.

Conservation biodiversity hotspots in South America. Data from a 2011 assessment by Conservation International accessed via the Global Forest Watch.

Intact forest in Peru with overlying projections of areas receiving state sanctioned protection. Data accessed via Global Forest Watch.

Intact forest in Peru with overlying projections of areas receiving state sanctioned protection. Data accessed via Global Forest Watch.

With approximately 30 million people spread out over 1.3 million square kilometers, Peru scored high (70.36, 68th in the world) on the specific issue of biodiversity and habitat, nearly 14 percent higher than the average country in Latin America and the Caribbean. Recent deforestation assessments, however, indicate that its biodiversity remains threatened by a wide range of factors.

Global Forest Watch, an online forest monitoring system created through a partnership with the World Resources Institute, estimates that 58 percent of all land in Peru has greater than 75 percent forest cover, and 61 percent of the country has at least 10 percent forest cover, which sums up to 76.8 million hectares of tree cover as of 2012. Of this forest, 89 percent is primary forest, making Peru the ninth most forested country in the world.

New ecosystem maps of Peru that combine satellite data with the Carnegie Institution for Science’s advanced laser-based system reveal that Peru’s vegetation stores 6.9 billion metric tons of aboveground biomass, with terra firme forests storing twice as much carbon as the flood plains.

A map of forest loss within Peru from 2001-2012 in relation to overall forest cover in South America. Data provided by Infoamazonia and Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

(Left) Deforestation has increased from 2001 to 2012 in the most forested parts of Peru. (Right) Of all the change recorded in forest cover from 2001 to 2012, 89 percent was forest loss in comparison to only 11 percent gained. Data from Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

From 2001 through 2012, Peru lost more than 1.5 million hectares of tree cover, with 2012 trumping other years with a total of 246,000 hectares lost. Most of this forest loss was concentrated in areas that had greater than 75 percent forest cover. That means that the most forested land in Peru, with the highest biodiversity and species richness counts, is also the land that faces the greatest threat of deforestation.

These data reflect a steadily increasing pressure on forests worldwide. From 2000 to 2012, according to the EPI, a total of 2.3 million square kilometers of tree cover was lost globally due to small-holder agriculture (40 percent), cattle pasture (25 percent), large-scale agriculture (20 percent), logging operations (10 percent), and other causes (5 percent). Deforestation also creates 4 to 14 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions each year. Compared to tree cover extent in 2000, however, Peru’s forest loss over the subsequent 12 years ranks only 115th in the world.

Threats Facing Trees

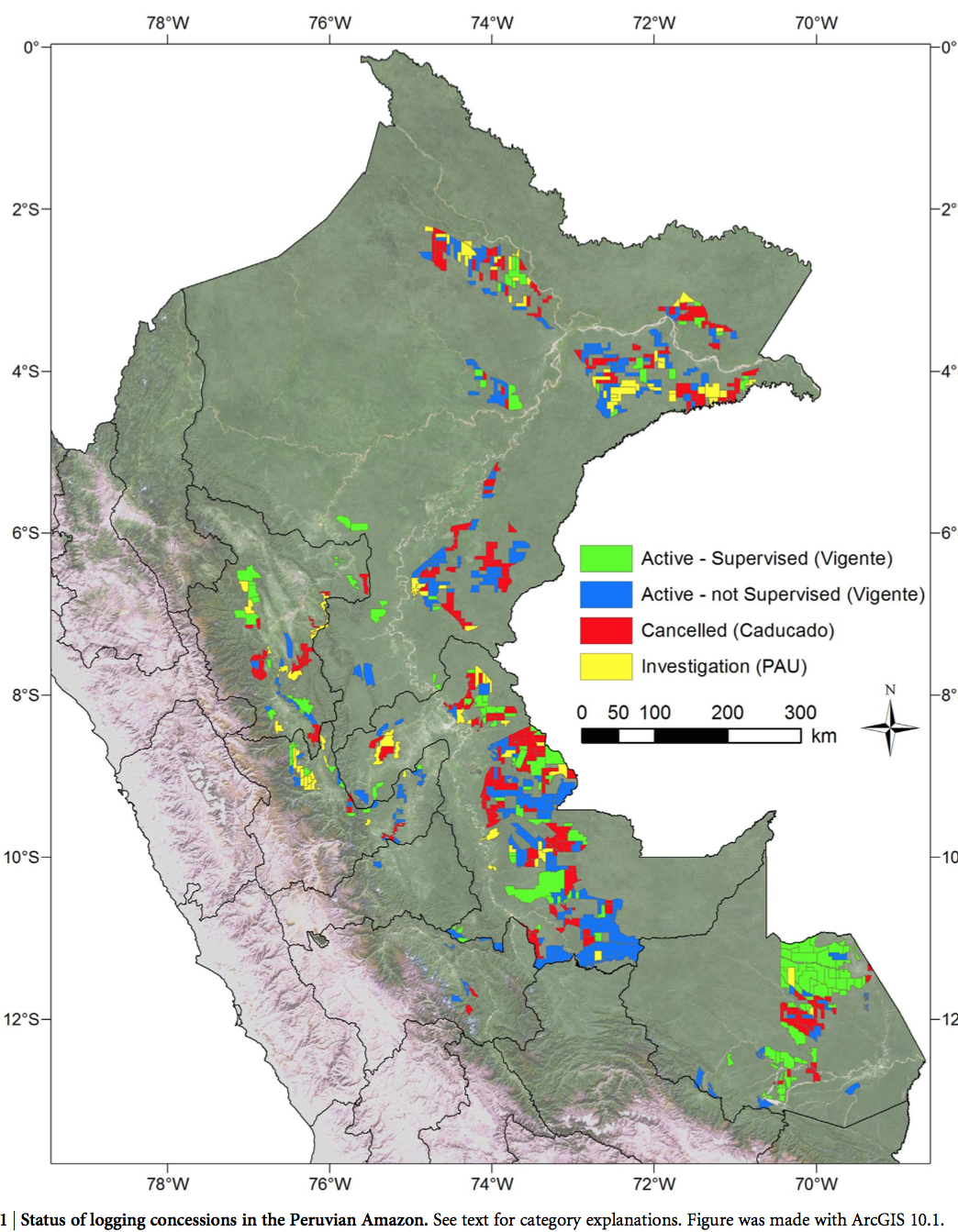

Despite a comprehensive forestry reform in 2000, when a forestry concession system was adopted, up to 90 percent of timber extracted from forests in Peru is likely done so illegally. This has been explained by a complex bureaucracy behind granting of permits and concessions, combined with a multi-player, hierarchical system of habilitación or “enabling.” A recent study in the Journal Nature’s Science Reports section, conducted by Matt Finer and colleagues of the Amazon Conservation Association, examined the outcomes of logging concession monitoring by OSINFOR, a government-appointed group that has assessed 64 percent of all active concessions. Finer reports that as of 2013, 43.5 percent of the 609 logging concessions were either cancelled or under investigation for major violations, and only 20 percent had been granted a clean bill of health. A surprisingly common problem OSINFOR unearthed was the use of permits to log timber in areas outside the concession, rather than within it, indicating once more that forestry reform remains unsuccessful in Peru currently.

The status of logging concessions in Peru in 2013, showing active and cancelled concessions, as well as those under investigation. Adapted from Finer et al., 2014. Click to enlarge.

“These findings lead us to conclude that the regulatory documents designed to promote sustainable logging are instead enabling illegal logging,” state Finer and colleagues in their report published this year.

Peru has not escaped the world’s incessant and strident call for oil palm, either. A study in 2011 by Victor Gutierrez-Velez of Columbia University used satellite and field data to examine high- and low-yield plantations in Peru’s Ucayali district, and found that 72 percent of all new plantations expanded into forested areas in the 2000s. While low-yield plantations, run by smallholders, expanded most (80 percent of overall expansion), 75 percent of high-yield plantation expansions involved forest conversions. For a large stakeholder, it was simpler to obtain permits for large tracts of land owned by the state than it was to negotiate the complexities of obtaining cleared land owned by multiple people.

One of the most rampant and startling uses of Peruvian Amazonian rainforest today is for oil mining concessions. In 2008 alone, the Peruvian government was scheduled to lease 64 blocks that covered a whopping 72 percent of the Peruvian Amazon (490,000 square kilometers). Only 12 percent of the Peruvian Amazon is protected and does not overlap with an oil block. Possibly the worst threat to the forest comes indirectly, by the installation of roads connecting previously inaccessible areas.

Maps of Peru’s oil block concessions in 2008, both leased and pending leasing, and their overlap with areas of high mammal and amphibian biodiversity. Data from Finer et al., 2008. Click to enlarge.

A map of Peru’s various natural resource concessions, including oil blocks, hydroelectric power projects, mining zones and roads. Data from InfoAmazonia. Click to enlarge.

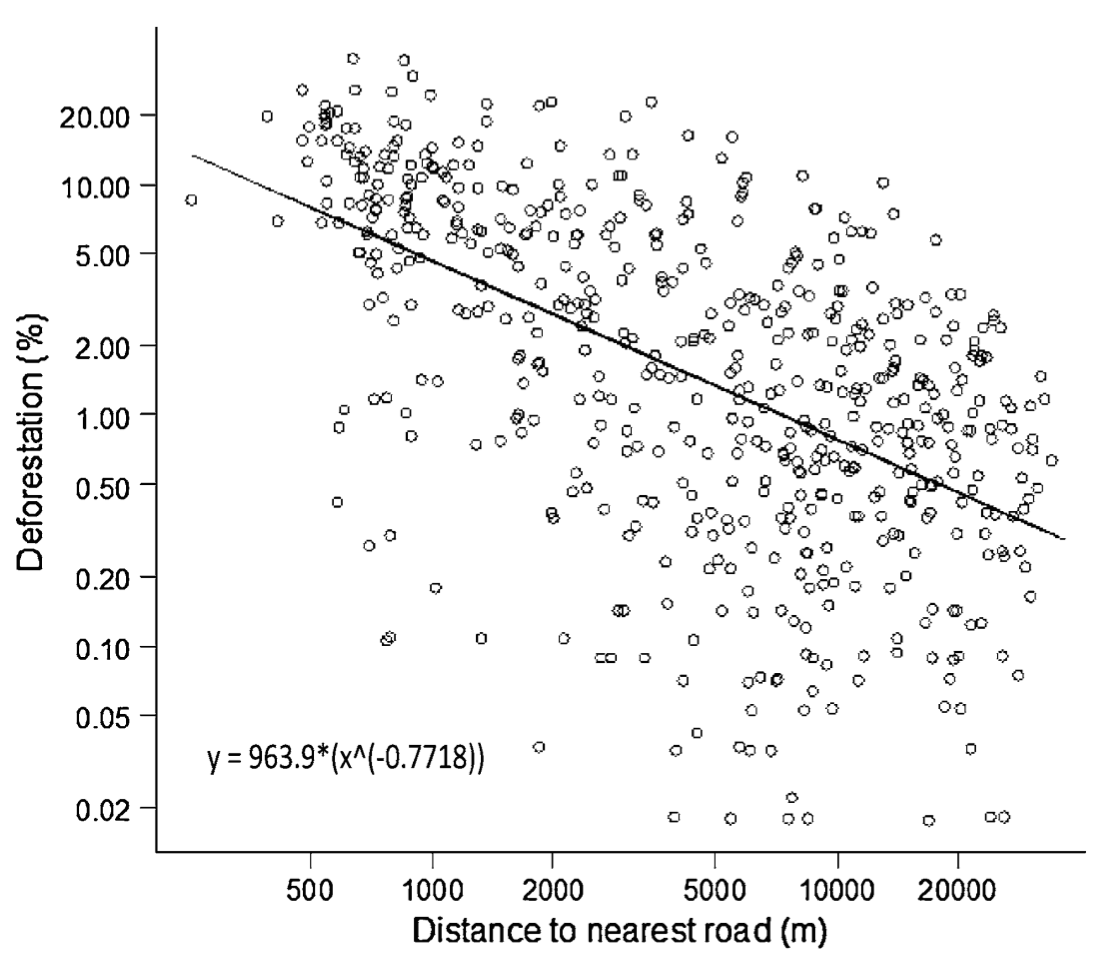

A graph showing the negative relationship between deforestation and the distance to roads – there is significantly more deforestation in areas easily accessible by road. Adapted from Vuohelainen et al., 2012. Click to enlarge.

According to Finer, in a study on oil blocks published in the open access journal PLoS One: “New access roads cause considerable direct impacts — such as habitat fragmentation — and often trigger even greater indirect impacts, such as colonization, illegal logging, and unsustainable hunting.”

These roads and unprotected rivers have given rise to a rapidly growing industry of gold mining, which brings with it untold destruction of the Peruvian Amazon. In the last decade, deforestation rates have skyrocketed as gold mining surged 400 percent along the Madre de Dios River in Peru.

These factors – logging, mining, and forest conversion – have severely damaged tropical rainforests in Peru, but they have not gone unnoticed. Peru’s active forestry, agriculture and wildlife protection government departments still strive to protect her extensive natural resources. In fact, despite these levels of deforestation, Peru’s biodiversity score assigned by the EPI has increased by over 15 points since 2002, when Peru ranked only 90th in the world, indicating progress of a nature in comparison to other countries.

Possible solutions to deforestation include the extraction of non-timber forest products, reform of the forestry law to include the complex social stratification in the timber industry, and an increased emphasis on ecotourism and conservation concessions, which have been shown to be highly effective at deterring deforestation.

The emperor tamarin (Saguinus imperator), one of Peru’s most charismatic and threatened species. Image credit: Mrinalini Erkenswick Watsa.

The emperor tamarin (Saguinus imperator), one of Peru’s most charismatic and threatened species. Image credit: Mrinalini Erkenswick Watsa.

Citations:

- Gregory P. Asner, David E. Knapp, Roberta E. Martin, Raul Tupayachi, Christopher B. Anderson, Joseph Mascaro, Felipe Sinca, K. Dana Chadwick, Sinan Sousan, Mark Higgins, William Farfan, Miles R. Silman, William Augusto, Llactayo León, Adrian Fernando and Neyra Palomino (2014). The High-Resolution Carbon Geography of Perú. A Collaborative Report of the Carnegie Airborne Observatory and the Ministry of Environment of Perú.

- Cossío R, Menton M, Cronkleton P and Larson A. 2014. Community forest management in the Peruvian Amazon: A literature review. Working Paper 136. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

Javier Escobal and Ursula Aldana. “Are nontimber forest products the antidote to rainforest degradation? Brazil nut extraction in Madre De Dios, Peru.” World Development 31.11 (2003): 1873-1887. - Finer M, Jenkins CN, Pimm SL, Keane B, Ross C (2008) Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002932

- Matt Finer, Clinton N. Jenkins, Melissa A. Blue Sky and Justin Pine (2014). Logging Concessions Enable Illegal Logging Crisis in the Peruvian Amazon. Nature.com Scientific Reports 4:4719

- Gutiérrez-Vélez, Víctor H., et al. “High-yield oil palm expansion spares land at the expense of forests in the Peruvian Amazon.” Environmental Research Letters 6.4 (2011): 044029.

- Hsu, A., J. Emerson, M. Levy, A. de Sherbinin, L. Johnson, O. Malik, J. Schwartz, and M. Jaiteh. (2014). The 2014 Environmental Performance Index. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy. Available at: http://www.epi.yale.edu.

- Robin R. Sears and Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez (2011). Forest Policy Reform and the Organization of Logging in Peruvian Amazonia, Development and Change 42(2): 609–631. International Institute of Social Studies.

- Swenson JJ, Carter CE, Domec J-C, Delgado CI (2011) Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon: Global Prices, Deforestation, and Mercury Imports. PLoS ONE 6(4): e18875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018875

- Anni Johanna Vuohelainen, Lauren Coad, Toby R. Marthews, Yadvinder Malhi, Timothy J. Killeen (2012). The Effectiveness of Contrasting Protected Areas in Preventing Deforestation in Madre de Dios, Peru. Environmental Management 50:645–663

Image Contributions

- Forest cover of Manaus Rainforest by Phillip Harris under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic License

- Stacked timber by Alan Partridge via a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 License

Related articles

NASA: Forest loss leaps in Bolivia, Mekong region

(08/08/2014) New satellite data from NASA suggests that deforestation is sharply increasing in Bolivia and Mekong countries during the second quarter of 2014.

Stunning high-resolution map reveals secrets of Peru’s forests

(07/30/2014) Peru’s landmass has just been mapped like never before, revealing important insights about the country’s forests that could help it unlock the value healthy and productive ecosystems afford humanity.

Peruvian oil spill sparks concern in indigenous rainforest community

(07/29/2014) A ruptured pipeline that spilled tens of thousands of gallons of crude oil into the Marañón River in late June is fueling concerns about potential health impacts for a small indigenous community.

Short-eared dog? Uncovering the secrets of one of the Amazon’s most mysterious mammals

(07/28/2014) Fifteen years ago, scientists knew next to nothing about one of the Amazon’s most mysterious residents: the short-eared dog. Although the species was first described in 1883 and is considered the sole representative of the Atelocynus genus, biologists spent over a century largely in the dark about an animal that seemed almost a myth.

Peru slashes environmental protections to attract more mining and fossil fuel investment

(07/23/2014) In an effort to kickstart investment in mining and fossil fuels, Peru has passed a controversial law that overturns many of its environmental protections and essentially defangs its Ministry of Environment. The new law has environmentalists not only concerned about its impact on the country but also that the measures will undermine progress at the up-coming UN Climate Summit in December.

Roads through the rainforest: an overview of South America’s ‘arc of deforestation’

(07/21/2014) When a new road centipedes its way across a landscape, the best of intentions may be laid with the pavement. But roads, by their very nature, are indiscriminate pathways, granting access for travel and trade along with deforestation and other forms of environmental degradation. And as the impacts of roads on forest ecosystems become clear, governments and planning agencies reach a moral crossroads.

Fly and wasp biodiversity in Peru linked to strange defense strategy

(06/18/2014) Entomologists working in Peru have revealed new and unprecedented layers of diversity amongst wasps and flies. The paper, published in the journal Science, also describes a unique phenomenon in which flies actually fight back and kill predatory parasitic wasps.

Feather forensics: scientist uses genes to track macaws, aid bird conservation

(06/17/2014) When a massive road project connected the ports of Brazil to the shipping docks of Peru in 2011, conservationists predicted widespread impacts on wildlife. Roads are a well-documented source of habitat fragmentation, interfering with access to available habitat for many terrestrial and tree-dwelling species. However, it wasn’t clear whether or not birds are able to fly over these barriers.

Oil drilling causes widespread contamination in the Amazon rainforest

(06/13/2014) Decades of oil extraction in the Western Amazon has caused widespread pollution, raising questions about the impact of a new oil boom in the region, according to a team of Spanish researchers presenting at a conference in California.