This is the second part of a series, Part 1 of which discusses the formation of Sankuru Nature Reserve and the general state of bonobos.

The bonobo (Pan paniscus) is a species of great ape found only in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It has declined precipitously in response to habitat destruction and poaching, much of which is due the civil unrest that has plagued the country for decades.

To safeguard the 29,000 to 50,000 individuals that remain, Sankuru Nature Reserve was established in 2007 by the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN), which is DRC’s park authority, along with the Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), and its local partner, Action Communautaire pour les Primates du Kasai (ACOPRIK). However, while touted as the largest swath of protected continuous great ape habitat in the world, the reserve is still losing thousands of hectares of forest every year.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are genetically distinct from chimpanzees, having diverged 1.5 to 2 million years ago after the formation of the Congo River separated the two groups. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

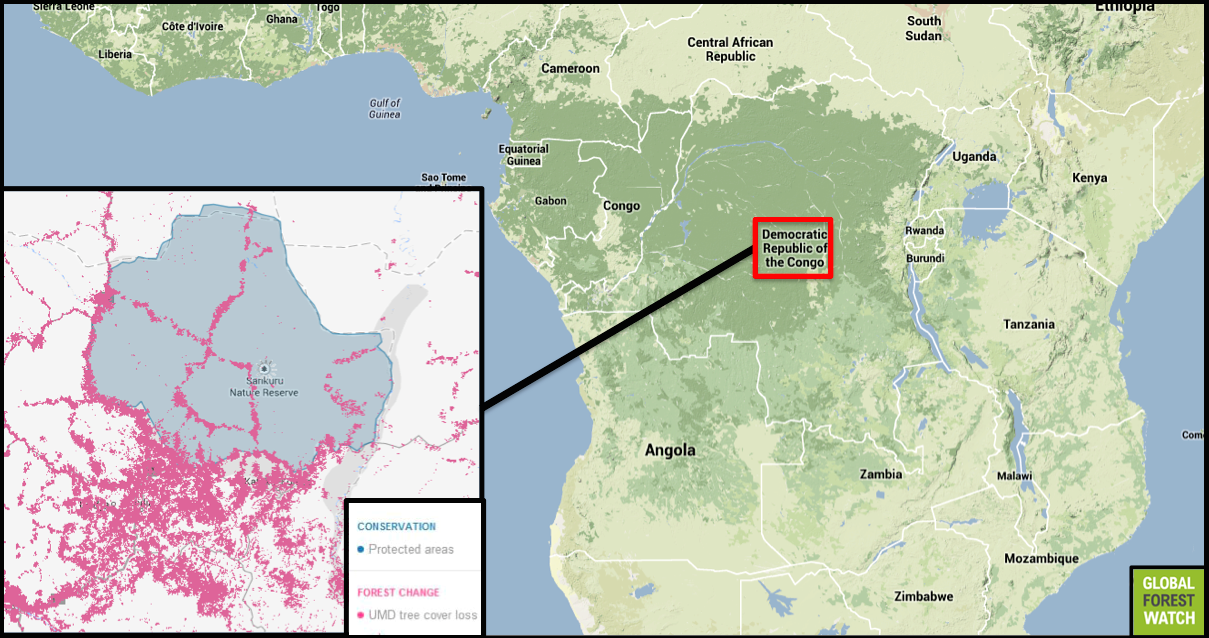

According to Global Forest Watch, most of the deforestation is occurring along roads that effectively split the reserve into five separate parts. This fragmentation is made even worse by extensive burning along the roads, which may be evidence of illegal charcoal production, a problem rife throughout the DRC.

This fragmentation is very problematic for bonobos, and may be limiting their movements across the reserve – and, thus, the exchange of their genes. A study led by Dr. Jena Hickey of Cornell University and the University of Georgia found that bonobos avoid areas of high human activity and forest fragmentation.

“The results of the study demonstrate that human activities reduce the amount of effective bonobo habitat and will help us identify where to propose future protected areas for this great ape,” Hickey said.

Sankuru Nature Reserve has lost more than one percent of its forest cover in less than a decade. While touted as the world’s largest continuous ape habitat, the deforestation is happening mostly along roads that criss-cross the park, fragmenting its forests. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

There have been more than 50 observable fires in Sankuru just during the past week (7/06 – 7/12). Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

A close-up view of satellite imagery showing the extant of deforestation and burning in Sankuru Nature Reserve. An active fire can be seen in the left of the photograph. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch.

The researchers found that distance from agricultural areas was the most important predictor of bonobo presence. In addition to the discovery that only 28 percent of the bonobo range is classified as suitable for the species, the researchers also found that only 27.5 percent of suitable bonobo habitat is located in existing protected areas.

In other words, less than eight percent of bonobo habitat is currently protected.

“Bonobos that live in closer proximity to human activity and to points of human access are more vulnerable to poaching, one of their main threats,” said Dr. Janet Nackoney, a Research Assistant Professor at University of Maryland and second author of the study. “Our results point to the need for more places where bonobos can be safe from hunters, which is an enormous challenge in the DRC.”

According to Michael Hurley, Executive Director of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) based Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), which runs the Sankuru Nature Reserve, deforestation and bushmeat hunting have severely impacted bonobos. Protection of the reserve’s eastern population, which is still relatively unscathed, will required an aggressive environmental education drive.

“The eastern half of the reserve is still heavily forested and there still is an abundance of bonobos,” he said. “They are under threat by bushmeat hunting. We have implemented education campaigns in the region, especially in bushmeat markets to protect them. In addition we have implemented monitoring and protection patrols, but insufficient funding has not allowed consistent protection.”

Scientists believe bonobos will continue to decline for the next 45 to 55 years due to growing threats and the the animal’s low reproductive rate.

In addition, certain bonobo body parts are sought after and used by local people in the mistaken believe they enhance sexual vigour or strength. While the exact number of bonobos poached cannot be known, the many bonobo body parts available at markets around the reserve indicate that poaching may be happening at a large scale.

|

For clarification, while Sankuru Nature Reserve offers the largest amount of continuous protected area in great ape habitat, it does not have the largest population of bonobos in the DRC. Contention surrounds the premise that the reserve functions as prime bonobo habitat, which will be explored in more detail in the fourth part of this series.

|

}}

Related articles

Will the last ape found be the first to go? Bonobos’ biggest refuge under threat (Part I)

(07/16/2014) Bonobos have been declining sharply over the past few decades. In response, several non-profit organizations teamed up with governmental agencies in the DRC to create Sankuru Nature Reserve, a massive protected area in the midst of bonobo habitat. However, the reserve is not safe from deforestation, and has lost more than one percent of its forest cover in less than a decade.

The last best place no more: massive deforestation destroying prime chimp habitat in Uganda

(07/09/2014) The Kafu River, which is about 180 kilometers (110 miles) long, is part of a vast chimpanzee habitat that includes forest reserves and several unofficial protected areas. However, this region of Uganda is losing a significant portion of valuable chimpanzee habitat, and at least 20 percent of the forest cover along the Kafu River has disappeared since 2001.

Sold into extinction: great apes betrayed by protectors

(07/09/2014) In what appears to be corruption in high places, the international body charged with protecting endangered species has turned a blind eye to massive illegal trade of endangered Great Apes. This was my distinct impression on reading the Great Apes report prepared by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Secretariat for the 65th CITES Standing Committee meeting, which will take place in Geneva in early July this year.

Bigfoot found? Nope, ‘sasquatch hairs’ come from cows, raccoons, and humans

(07/01/2014) Subjecting 30 hairs purportedly from bigfoot, the yeti, and other mystery apes has revealed a menagerie of sources, but none of them giant primates (unless you count humans). Using DNA testing, the scientists undertook the most rigorous and wide-ranging examination yet of evidence of these cryptic—perhaps mythical—apes, according to a new study in the Proceedings of Royal Society B.

Broken promises no more? Signs Sabah may finally uphold commitment on wildlife corridors

(06/23/2014) Five years ago an unlikely meeting was held in the Malaysian state of Sabah to discuss how to save wildlife amid worsening forest fragmentation. Although the meeting brought together longtime adversaries—conservationists and the palm oil industry—it appeared at the time to build new relationships and even point toward a way forward for Sabah’s embattled forests.

The palm oil diet: study finds displaced orangutans have little else to eat

(06/20/2014) In a recent study, researchers assessed how orangutans have adapted to living among oil palm plantations on Borneo. They found that while orangutans have adapted to the island’s human-transformed landscapes better than expected, oil palm plantations are unable to sustain orangutan populations in the long-term.

Apeidemiology: researchers model ape disease transmission for the first time

(06/20/2014) In a nine-year-long study published recently in PLOS ONE, a team of researchers attempted to understand how diseases spread and differ among orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii), creating the first-ever epidemiological model for great ape populations.