This is the third part of a series. Part 1 discusses the formation of Sankuru Nature Reserve and the general state of bonobos. Part II discusses the specific threats faced by bonobos and the reserve.

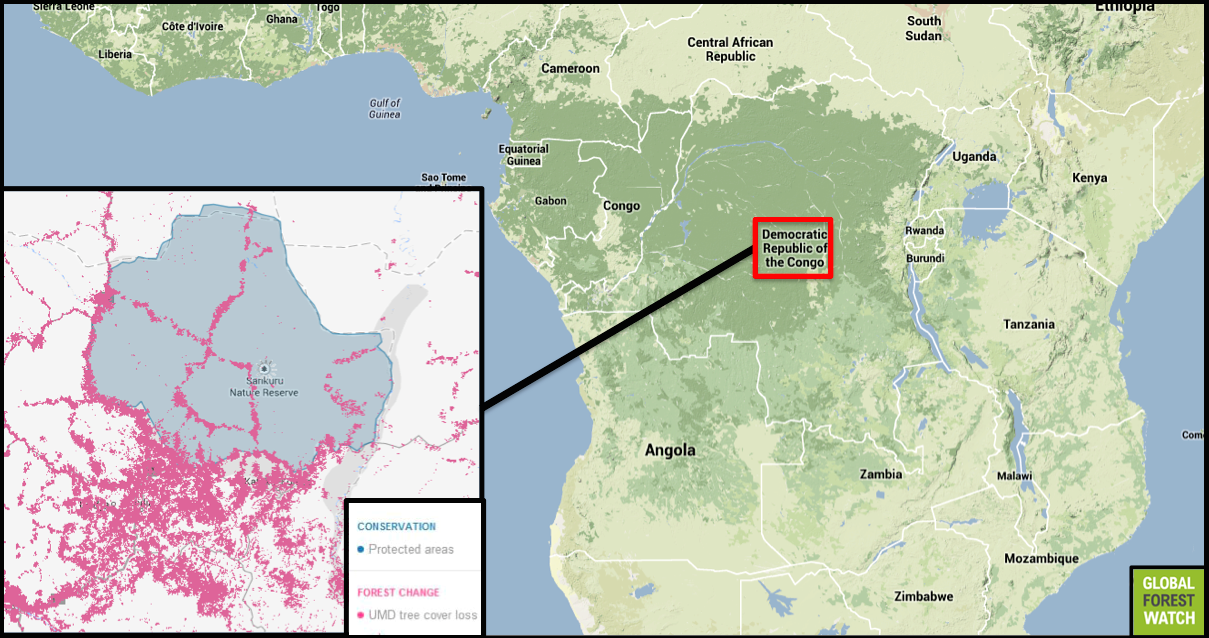

Tropical forests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are being cleared at a rapid clip, with nearly six million hectares lost from 2001 to 2013, according to data from Global Forest Watch. In other words, almost three percent of its total land area was deforested in 12 years. The DRC is home to a unique species of great ape, the bonobo (pan paniscus), which has been in steep decline due to high levels of poaching and deforestation in the war-ravaged country.

Sankuru Nature Reserve was established in 2007 primarily for bonobo protection. The largest continuous protected great ape habitat in the world, Sankuru is still losing large swaths of forests to burning and other activities, primarily along roads that transect the center of the reserve.

With 107 million hectares, the DRC contains the largest area of Congo rainforest of any country, amounting to 60 percent of Central Africa’s lowland forest cover. However, the country is being rapidly deforested, losing approximately 500,000 hectares every year. Bonobo range (encircled in yellow) is heavily affected by forest loss. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

However, hope exists, both from human efforts – and from the apes themselves.

Bonobos contribute significantly to forest regeneration. Recent studies by Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI) have shown that bonobos spread seeds to other parts of the forest, and promote their growth. Indeed, they found up to 97 percent of seeds in bonobo feces germinate. Since bonobos have large home ranges, they can help maintain healthy forests by spreading new generations of plants throughout their habitat.

Bonobos eat fruit, leaves, pith, flowers, seeds, nuts, insects, and sometimes small mammals such as duiker, flying squirrels, and monkeys. They also have been observed foraging from streams and marshlands for aquatic plants, insects, and possibly fish. In total, bonobos are known to eat the seeds of more than 100 species of trees, lianas, and herbaceous plants.

“Our studies have found over 139 species of plants and trees that bonobos use [to eat],” Hurley said. “However, bonobos also use other species to make nests, to utilize plant medicines and to eat shoots and leaves.

In its entire lifespan, a bonobo disperses nearly 12 million seeds, equalling about nine tons in weight. The great majority of the seeds passed through a bonobo’s gut are viable, and seeds present in bonobo feces germinate faster and at a higher rate than those not eaten and digested.

Furthermore, seeds disseminated by this process – called “endozoochory” — are better able to escape seed predators, as dung beetles are quickly attracted to feces and often bury them.

However, the relationship between bonobos and plants goes both ways.

“If a large variety of plants and trees are not abundant in a region, the region will not support bonobos and other primates,” said Hurley.

Bonobos live only in the DRC. There are an estimated 29,000 – 50,000 individuals left in existence. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Protection of bonobo habitat intensified in 2002 with the establishment of the Bonobo Peace Forest. Together with the Global Conservation Fund of Conservation International, along with various scientists, local leaders, and government officials, BCI started piecing together small conservation easements in the heart of bonobo habitat. Today, they have created a network of protected areas spanning 31,000 square kilometers (12,000 square miles), an area the size of the U.S. states of Massachusetts and Rhode Island combined. The Bonobo Peace Forest works in concert with local communities, with sub-programs focused on community development, sustainable agriculture, and education.

However, many of the protected areas included in the Peace Forest are isolated from one another. Since bonobos shy away from human-altered and inhabited areas, protected large swaths of continuous habitat is needed to allow populations to mix and exchange genes.

A study conducted by various institutions around the world and published in Wildlife Conservation Society in 2013 found that because of human influx into and alteration of forests south of the Congo River, only 28 percent of bonobo range remains habitable — and less than seven percent is currently protected.

Which is why Sankuru Nature Reserve is so important. Spanning 23,161 square kilometers (8,943 square miles), the reserve was set up to provide a large, continuous, protected habitat for bonobos. It operates under the blessing of the DRC government, and is managed by nonprofit organizations and local communities.

Sankuru Nature Reserve has lost more than one percent of its forest cover in less than a decade. While touted as the world’s largest continuous ape habitat, the deforestation is happening mostly along roads that criss-cross the park, fragmenting its forests. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

According to the DRC’s Prime Minister, Matata Ponyo Mapon, the protection the country’s environment is one of his government’s economic development. Mapon said the establishment of of Sankuru Nature Reserve increases the country’s total area of protected land to 10.47 percent, bringing the country closer to its goal of 15 percent.

“Sankuru Reserve is a jewel and a blue chip for us and was created in the framework of community participative conservation and so far we have zoned it to guarantee the rights of the local population,” Mapon said.

The Sankuru project was also highlighted as a leading example of a potential REDD project in at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Conference of the Parties (COP) in 2007.

However, the reserve has been losing thousands of hectares of forest per year, and little seems planned to stymie deforestation in the area. In addition, poaching is also rampant in the area, with bonobos hunted to supply the bushmeat demand, as well as for traditional medicine.

According to Ashley Vosper of the Wildlife Conservation Society, more research is needed to understand the full impact humans are having on bonobo populations, as well as develop effective conservation strategies for the future.

“For bonobos to survive over the next 100 years or longer, it is extremely important that we understand the extent of their range, their distribution, and drivers of that distribution so that conservation actions can be targeted in the most effective way and achieve the desired results,” Vosper said.

|

For clarification, while Sankuru Nature Reserve offers the largest amount of continuous protected area in great ape habitat, it does not have the largest population of bonobos in the DRC. Contention surrounds the premise that the reserve functions as prime bonobo habitat, which will be explored in more detail in the fourth part of this series.

|

Related articles

Poaching, fires, farming pervade: protecting bonobos ‘an enormous challenge’ (Part II)

(07/17/2014) Sankuru Nature Reserve in the DRC was established in 2007 to safeguard the 29,000 to 50,000 bonobos that remain in existence. However, while touted as the largest swath of protected continuous great ape habitat in the world, the reserve is still losing thousands of hectares of forest every year. Burning, bushmeat hunting, and agricultural expansion are taking a large toll on the endangered great ape.

Will the last ape found be the first to go? Bonobos’ biggest refuge under threat (Part I)

(07/16/2014) Bonobos have been declining sharply over the past few decades. In response, several non-profit organizations teamed up with governmental agencies in the DRC to create Sankuru Nature Reserve, a massive protected area in the midst of bonobo habitat. However, the reserve is not safe from deforestation, and has lost more than one percent of its forest cover in less than a decade.

DRC deforestation escalates despite resource shortages, protests, rape, homicide

(07/10/2014) Road construction, the promise of employment, and the conversion of forest to farmland – the effects of logging tropical forests are often not confined to the boundaries of the concessions, where, in the best case, a timber company has gained legal access to harvest trees. Along the Congo River in the northern Democratic Republic of Congo, recent data showing probable forest loss demonstrate the often-unforeseen consequences of timber harvesting.

Oil, wildlife, and people: competing visions of development collide in Virunga National Park

(07/07/2014) What does SOCO’s withdrawal really mean for the future of Virunga National Park? – Part II. Located in the eastern DRC, Virunga is the first national park created in Africa, a World Heritage Site and home to mountain gorillas, of which fewer than 900 remain. As such, SOCO’s announcement to suspend activities followed in the wake of a concerted campaign led by WWF to “draw the line” to save Virunga from devastation by prospective oil drilling.

New report: illegal logging keeps militias and terrorist groups in business

(06/30/2014) Released last week by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) during the first United Nations Environment Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya, a new report found that together with other other illicit activities such as poaching, illegal deforestation is one of the top money-makers for criminal groups like Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab.

Grenades, helicopters, and scooping out brains: poachers decimate elephant population in park

(06/15/2014) Over the last two months, poachers have killed 68 African elephants in Garamba National Park representing around four percent of the population. Poachers have used helicopters, grenades, and chainsaws to undertake their gruesome trade, and, for the first time, the park has recorded that the criminals are removing the elephant’s brains in addition to tusks and genitals.

Hope in the Heart of Darkness: huge population of chimpanzees discovered in the DRC

(05/20/2014) A recent study describes a new population of chimpanzees, which forms a continuous cultural group inhabiting an area of at least 50,000 square kilometers (19,000 square miles). The population, estimated to consist of many thousands of individuals, shares a unique set of learned skills that are passed on from generation to generation.