New research shows African apes likely to be affected by palm oil, but there’s hope, says the author

As palm oil producers increasingly look to Africa’s tropical forests as suitable candidates for their next plantations, primate scientists are sounding the alarm about the destruction of ape habitat that can go hand in hand with oil palm expansion. A study recently published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology sought to take those warnings a step further by quantifying the overlap in suitable oil palm land with current ape habitat.

“It’s a huge worry,” said lead author Serge Wich of oil palm expansion in Africa and its effects on ape populations. The primate biologist from Liverpool John Moores University added, “It’s probably the top threat at the moment.”

Western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) in Gabon, a gorilla subspecies whose habitat is threatened by palm oil development. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

As a writer covering science and the environment in Africa, I often have the opportunity to pester primatologists like Wich with questions about their latest research and trips to the continent. They’re typically fascinating people whose drive to study great apes carries them into impossibly dense forests, up the flanks of steep volcanoes, and through war-torn states where their study subjects and rebel groups seek solace in the same refuges. And they all seem to come back with the same conclusions – our primate cousins are in trouble.

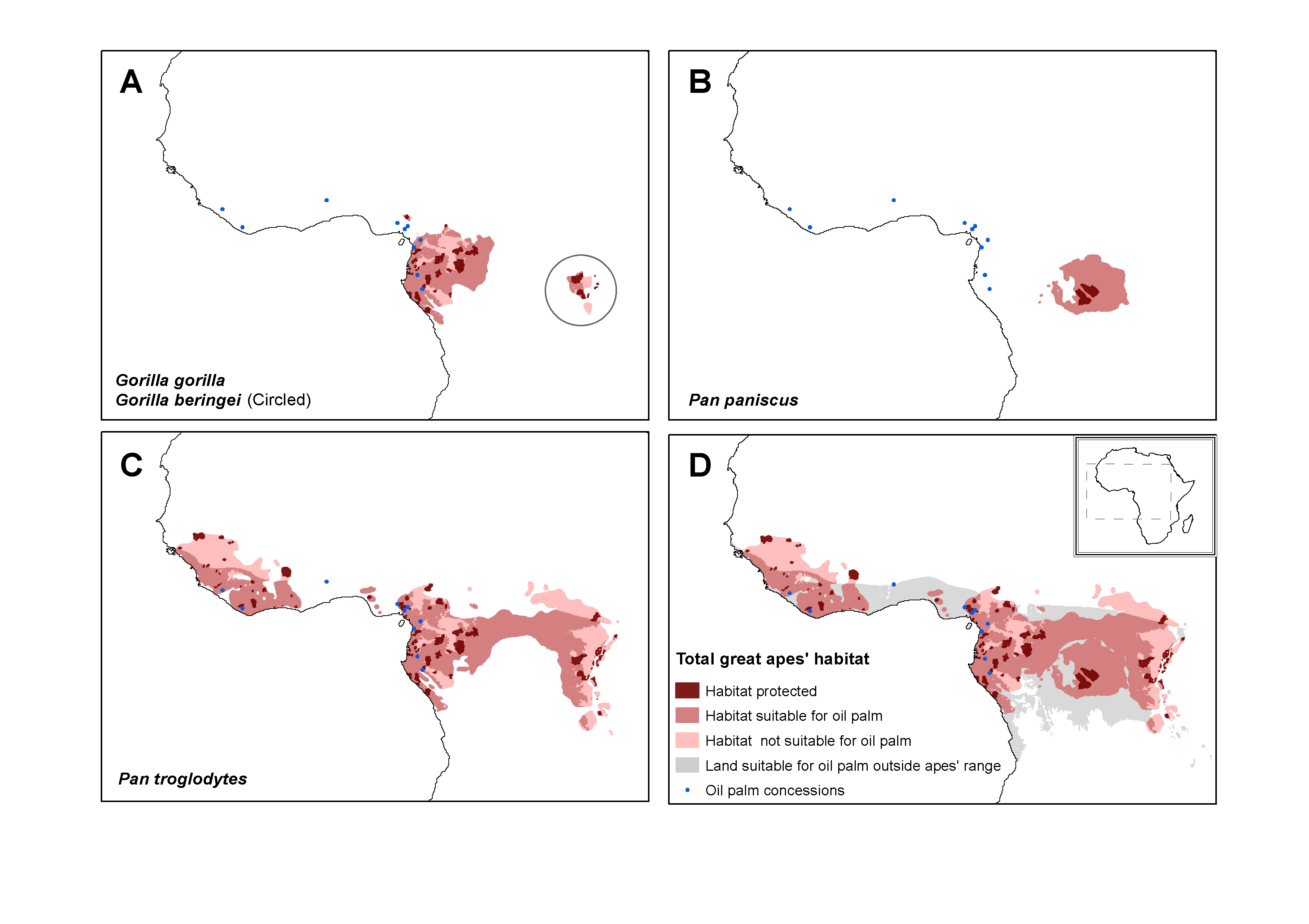

Wich has spent several decades studying apes in Southeast Asia. He watched the decline of orangutans as they lost their habitat, particularly due to the demand for cheap palm oil for inclusion in a wide variety of processed foods, and he wondered if the same problems might arise in Africa. So he and his team sought to quantify the current known range of chimpanzees and gorillas compared to spots that might also work for oil palm cultivation. In a comprehensive analysis of satellite data covering the band of tropical forest spanning the girth of the African land mass, they mapped out where the where palm oil plantations currently overlap with great ape habitat. They also looked at favorable areas for future expansion of the crop.

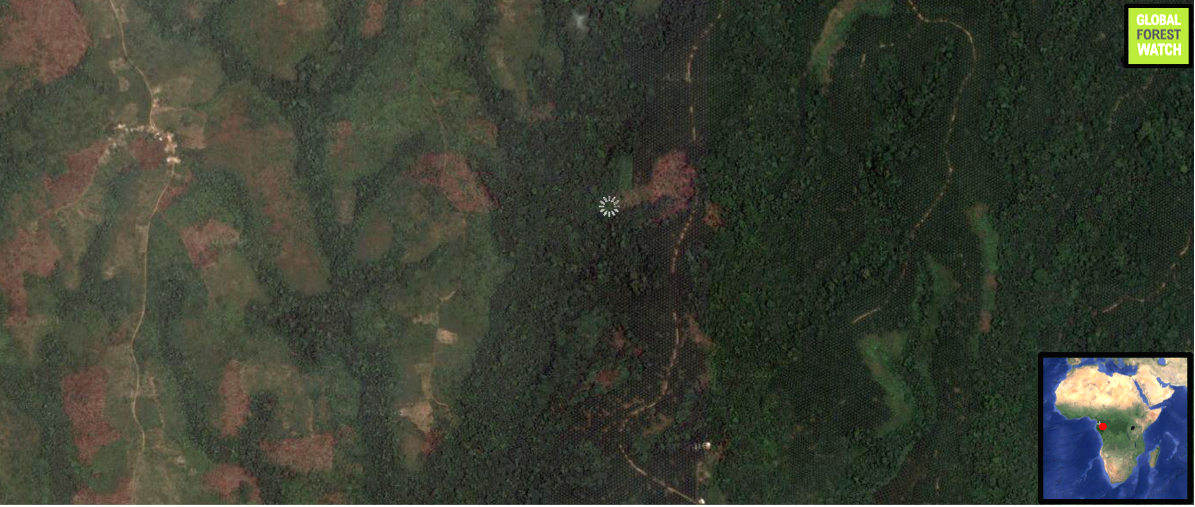

Cameroon, home to many great ape species, is increasingly affected by palm oil development. According to data by Global Forest watch, Cameroon lost nearly 500,000 hectares of forest cover between 2001 and 2013, with almost half of that occurring in the region above. Click to enlarge.

Palm oil is used as an ingredient in a plethora of products — from toothpaste to gummy bears — and is produced primarily by the palm species Elaeis guineensis. Primarily cultivated in Indonesia, plantation development has led to the clearing of millions of hectares of the country’s forests. According to data from Global Forest Watch, the province of West Kalimantan, in Indonesian Borneo, lost approximately two million hectares of forest from 2001-2013 alone. This represents a sixth of the region’s total land area, which is dominated by oil palm plantations.

Ironically, E. guineensis is originally from western Africa. The same humid forests and fertile soils that make for good oil palm production also nurture the dense cover and food sources that offer apes protection and sustenance. Right now, almost 60 percent of the land in use for oil palm production overlaps with ape habitat.

What’s more, Wich and his colleagues point out that nearly 40 percent of the land that hasn’t yet been converted to oil palm is also ape habitat that is not currently protected. From the lessons learned in Southeast Asia, they point out the need to be deliberate in how the crop is expanded in Africa.

The creation of large-scale palm oil plantations is “decimating orangutan habitat” in Southeast Asia, said primatologist Martha Robbins of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, who was not involved in this study. “And it’s moving in quickly in central Africa. It’s not there yet, but it’s going to come really fast, unless people do something about it.”

Mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) are listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, but their habitat is not threatened by palm oil development. Photo by John C. Cannon.

Her worry is for the western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) living in Gabon, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea and the Republic of Congo. With more than 100,000 animals, their numbers are high compared to orangutans and certainly to the 800 or so remaining mountain gorillas (which by and large don’t overlap much with land that’s viable for oil palm cultivation). But as more plantations crop up, she said, and with them the demand for gorilla meat – already firmly a part of many cultures in central Africa – she too is worried.

“Realistically speaking, in 20 years time, we will not have any where near that number,” Robbins said.

The trouble is that oil palm expansion does hold the promise of generating income and employment for cash-strapped developing countries. Sometimes, the governments in these places take a measured approach to this sort of expansion. In Gabon, Robbins pointed out, leaders are trying to find places for plantations that won’t interfere with the country’s herds of forest elephants.

The entirety of bonobo (Pan paniscus) habitat is deemed suitable for oil palm.

As Wich and his colleagues write in the paper, in addition to increasing the efficiency of production on lands that are already dedicated to palm oil cultivation, the prevailing solution is to develop what are known as degraded lands.

This notion of setting aside intact and bio-diverse forests for conservation and confining palm oil cultivation to spaces that have already been deforested and have low biodiversity is the thrust of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, known by its acronym, RSPO. But, it turns out that some companies have taken a somewhat liberal view of the term “degraded,” cautioned Joshua Linder, moving into areas that, though they may have been logged recently, still provide habitat for many different plants and animals. Linder studies primates in Cameroon and is a biological anthropologist at James Madison University in Virginia.

Industrial oil palm cultivation “is the greatest threat to come [for ape populations],” Linder said, adding that the members of the RSPO need to come to a consensus on a definition for what constitutes degraded land. According to Linder, the guidelines must also take into account the areas surrounding plantations, since this sort of development often “will exacerbate bush meat hunting and deforestation rates” as newly constructed roads and the promise of employment will bring more people into previously uninhabited spots in the forest, echoing Martha Robbins’ concerns for western gorillas.

Comparisons of ape habitat and locations of both existing and possible palm oil plantations. Figure by Wich et al., 2014, published in Current Biology. Click to enlarge.

Linder has been critical of the RSPO, which can sometimes lack the tools to enforce sustainability requirements. In fact, he put together his own paper for the journal African Primates in 2013 detailing the threats of new palm oil development in Africa on primate biodiversity. He told mongabay.com that companies can use RSPO certification as a marketing tool, ostensibly demonstrating to consumers that the palm oil they produce isn’t harming forests, while ignoring the spirit of the guidelines.

Wich said he agrees that the RSPO needs to come up with more definitive regulations to hold companies accountable. But he also sees the promise of having a single organization that can help ensure that the oil palm produced in Africa doesn’t come at the cost of greater forest lost and, by extension, the last remaining bastions of ape habitat. It’s unrealistic to try to stop palm oil production altogether, he said, so “we have to steer it away from areas of pristine rain forests or logged areas where there is a lot of biodiversity.”

He also said that consumers themselves have a powerful set of tools to make sure that the companies they buy products from are producing palm oil responsibly. New technology has made it easier than ever for someone to figure out if the products they buy contain palm oil and, if so, where it comes from. They can also provide feedback to those companies instantaneously from their devices. And tools like the maps available at Global Forest Watch allow even those of us without PhDs to see which companies are setting up concessions in or near forested areas.

Satellite image of cleared land (left) and a plantation (right) in Cameroon. Courtesy of Global Forest Watch. Click to enlarge.

Technological gains are also providing a boon for Wich and his fellow researchers. Images from satellites and even drones are providing higher resolution data, allowing them to pinpoint, for example, where forest loss is occurring in near-real time.

And for Wich, therein lies his hope that we can effectively manage oil palm production so that it provides affordable vegetable oil to the world in a way that can both offer economic benefits to forested countries and protect ape populations.

With all of the monitoring tools available, “There’s an enormous amount of awareness,” Wich said. “It’s more difficult for forests to disappear and then years later for people to find out. And that makes it much easier to put pressure on governments and companies these days.”

It’s that pressure, he said, that will ultimately change the course for African apes in the face of oil palm expansion.

Citations:

- Linder, J. M. (2013). African primate diversity threatened by “new wave” of industrial oil palm expansion. African Primates, 8, 25-38.

Chicago- Wich, S. A., Garcia-Ulloa, J., Kühl, H. S., Humle, T., Lee, J. S., & Koh, L. P. (2014). Will Oil Palm’s Homecoming Spell Doom for Africa’s Great Apes?. Current Biology.

Chicago

}}

Related articles

True stewards: new report says local communities key to saving forests, curbing global warming

(07/24/2014) Deforestation is compromising forests around the world, destroying vital habitat and causing greenhouse gases emissions that are contributing to global warming. A new report released today finds a possible solution: protecting forests by empowering the local communities that live within them.

Desperate measures: researchers say radical approaches needed to beat extinctions

(07/24/2014) Today, in the midst of what has been termed the “Sixth Great Extinction” by many in the scientific community, humans are contributing to dizzying rates of species loss and ecosystem changes. A new analysis suggests the time may have come to start widely applying intensive, controversial methods currently used only as “last resort” strategies to save the word’s most imperiled species.

(07/21/2014) After more than four and a half years of camera trap footage, the results are encouraging: 36 mammal species, of which more than half are legally protected, are prospering in this most surprising of spots: an oil palm plantation in the province of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo.

30% of Borneo’s rainforests destroyed since 1973

(07/16/2014) More than 30 percent of Borneo’s rainforests have been destroyed over the past forty years due to fires, industrial logging, and the spread of plantations, finds a new study that provides the most comprehensive analysis of the island’s forest cover to date. The research, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, shows that just over a quarter of Borneo’s lowland forests remain intact.

The history of the contentious number behind zero deforestation commitments for palm oil

(07/15/2014) It was just after lunch, Monday, November 8th 2010 when it all began. At the time, it was innocent enough; there were certainly no ill intentions. Yet, looking back, I now see it as the moment that kicked off the polarizing debate that today splits the palm oil industry and that drowns out much needed sensible discussion around how forest protection and palm oil expansion might go hand in hand. The debate, with all its spin

and tension, has become the focus rather than that more important, bigger question.New palm oil sustainability manifesto met with criticism from environmentalists

(07/11/2014) This week several palm oil giants announced new environmental criteria for palm oil production. The companies say the initiative goes beyond the industry-leading standard set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), but two prominent environmental groups quickly disagreed, arguing the measure has substantial loopholes that will allow growers to continue destroying forests.

- Wich, S. A., Garcia-Ulloa, J., Kühl, H. S., Humle, T., Lee, J. S., & Koh, L. P. (2014). Will Oil Palm’s Homecoming Spell Doom for Africa’s Great Apes?. Current Biology.