Introduction of non-native species, de-extinction may work better than traditional conservation practices

Today, in the midst of what has been termed the “Sixth Great Extinction” by many in the scientific community, humans are contributing to dizzying rates of species loss and ecosystem changes. A new analysis published in Science refutes the value of common conservation measures, such as establishing protected areas, to preserve ecosystem integrity in the long term. It suggests the time may have come to start widely applying intensive, controversial methods currently used only as “last resort” strategies to save the word’s most imperiled species.

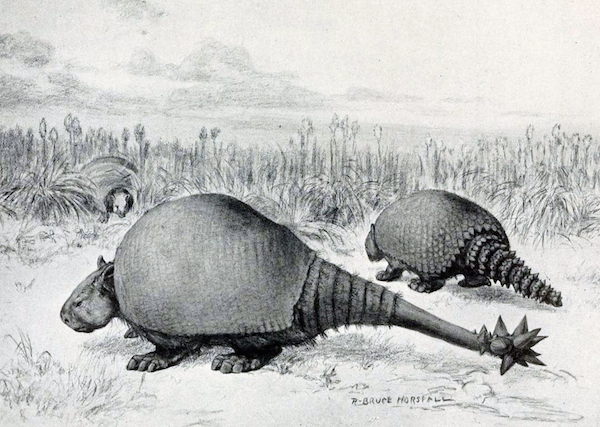

Since the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event occurred 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs along with 75 percent of all other plant and animal species on the planet, the earth has rebounded at an overall rate of species evolution that exceeded species extinction. That is, until humans began spreading around the globe. While prehistoric anthropogenic extinction is still something of a contentious subject, studies are increasingly pointing the finger of blame at humans for the demise of many of the world’s large animal species. For example, 15 North American megafauna genera such as the giant beaver (Castoroides species) and huge armadillo-like glyptodonts became extinct between 11,500 and 10,000 years ago – closely correlating to the arrival of humans on the continent.

Glyptodonts once roamed North America. They were the size of cars and were related to armadillos.

Australia had its own menagerie of megafauna – giant marsupials like the lion-size carnivore Thylacoleo carnifex and the rhino-like Zygomaturus diahotensis. Like the North American event, evidence correlates the extinctions of these species to the arrival of humans on the continent around 50,000 years ago.

Currently, species are disappearing at a rate estimated to be 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than the fossil record indicates for any time in history since the extinction event that took out the dinosaurs. According to the IUCN, nearly one in four mammals and one in eight birds is threatened with extinction within the next several decades. Plants are less well studied, but also appear to be disappearing as their pollinators vanish and their habitats change. One of the most swiftly declining groups is the amphibians; the IUCN currently lists 486 species as Critically Endangered, with 32 percent globally threatened.

The causes for these declines are many and varied, but human impact is often found at the root of the problem. With the world’s forests felled at a rate of approximately 50,000 hectares every day – an area roughly 10 times the size of the island of Bermuda – wildlife habitat is swiftly disappearing. Much of the deforestation is occurring in species-rich places like Indonesia, where trees are being cleared at a fast clip to make way for oil palm plantations. Global warming, fueled by human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, is changing climates in many areas of the world, making them inhospitable to the species that evolved to live in different conditions. For instance, an increase in droughts in Panama seems to be changing the composition of its forests. Habitat degradation, pollution, ozone depletion, and human-spread disease are all taking their toll on frogs around the world.

Marsupial lions (Thylacoleo carnifex) once roamed Australia. Biologists believe its ancestors were herbivores. Drawing by Nobu Tamura.

To hold-off extinctions and preserve habitat, the traditional conservation mindset involves keeping the wild as wild as possible. However, as human populations grow, the authors of the report suggest this will become increasingly more difficult. Even reintroductions of species once native to an area can be problematic and generally have low rates of success.

“Also, such reintroductions are often biased towards ‘charismatic’ animals, such as large mammals, regardless of how endangered they are compared to other species,” said coauthor Philip Seddon of the University of Otago in New Zealand.

Many plants need their seeds to be spread by certain animals. If those animals disappear, then the plants may become disadvantaged and may themselves disappear – along with any other species that depend on them. A previous study found that this appears to be contributing to forest changes in Panama, where wind-dispersed plants such as lianas are becoming more numerous than those that are animal-dispersed.

Seddon and his colleagues instead suggest a more holistic approach, where species are introduced to an area based on their ability to serve an ecological role – for instance, as seed-spreaders.

“Examples include the release of exotic species of giant tortoise to restore the grazing functions and seed dispersal lost through tortoise extinctions on islands in the Indian Ocean,” he said.

Short-faced bears (Arctodus simus) were larger than grizzlies and were once common in California. They became extinct around the time humans began spreading throughout North America. By Dantheman9758.

These types of introductions, collectively called “conservation introductions,” include the relocation of species to places outside their historical range if they are severely threatened.

“Examples of this include moving native birds, such as kakapo to predator-free offshore islands to protect them from exotic predators in mainland habitat,” Seddon said. “Other such efforts include establishing a facial cancer-free colony of Tasmanian Devils on Maria Island off the coast of Tasmania.”

Kakapos (Strigops habroptila) are flightless, nocturnal parrots native to New Zealand. Introduced mammals decimated the species, and it is currently critically endangered, with just 126 left in existence as of March, 2014. To save the the kakapo, all remaining individuals were moved off the mainland to three predator-free offshore islands, where they are closely monitored.

Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) are marsupial predators that once lived on Australia. However, fossil records indicate they vanished from the mainland, possibly due to expansion of humans and introduced dingoes. Relegated to the island of Tasmania, off Australia’s southern coast, the species is currently experiencing a rapid decline due to a cancer epidemic. Devils are particularly prone to cancer, but this natural propensity may be heightened due to human-made carcinogenic flame-retardants that were found in high levels in tissue samples taken from several of the animals. In effort to protect the species, an “insurance population” was established on another island near Tasmania.

Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) are currently experience a contagious cancer epidemic, which has wiped out 20 to 50 percent of the population on Tasmania. Photo by Menna Jones.

Introducing species to ecosystems to which they’re not native does come with risks. For instance, cane toads (Rhinella marina), native to South and Central America, were introduced to Australia in 1935 in effort to control sugar cane pests. However, they were ineffective at doing so, and since then have exploded throughout the eastern side of the continent, where they are depleting the food sources of native insectivores and poisoning the native predators that eat them.

Seddon acknowledges the risks and challenges involved in species introduction – and even the possibility of bringing back extinct species and subspecies through cloning or selective breeding.

“The prospect of bringing back extinct species through advanced technologies creates a further conundrum,” he said. “If potential de-extinction of multiple species does become a reality, which species should be resurrected, and which habitats should they be introduced to?”

However, the authors suggest the time has come where the reward of such controversial approaches may be worth the risk, stating “the realization that a return to a completely natural world is not achievable frees us to think about more radical types of conservation.”

Kakapos were thought to be functionally extinct in the 1970s, until a small population was found on Stewart Island. Photo taken on Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), New Zealand, one of the translocation sites, by Mnolf.

Citations:

- Seddon, P.J., Griffiths, C.J., Soorae, P.S., Armstrong, D.P. (2014). Reversing defaunation: restoring species in a changing world. Science 245(6192): 406-412.

Related articles

Too much of a good thing: fertilizer ‘one of the three major drivers of biodiversity loss this century’

(07/14/2014) The world’s grasslands are being destabilized by fertilization, according to a paper recently published in the journal Nature. In a study of 41 grassland communities on five continents, researchers found that the presence of fertilizer weakened grassland species diversity.

Only 15 percent of world’s biodiversity hotspots left intact

(07/14/2014) The world’s 35 biodiversity hotspots—which harbor 75 percent of the planet’s endangered land vertebrates—are in more trouble than expected, according to a sobering new analysis of remaining primary vegetation. In all less than 15 percent of natural intact vegetation is left in the these hotspots, which include well-known jewels such as Madagascar, the tropical Andes, and Sundaland.

Booming populations, rising economies, threatened biodiversity: the tropics will never be the same

(07/07/2014) For those living either north or south of the tropics, images of this green ring around the Earth’s equator often include verdant rainforests, exotic animals, and unchanging weather; but they may also be of entrenched poverty, unstable governments, and appalling environmental destruction. A massive new report, The State of the Tropics, however, finds that the truth is far more complicated.

Unrelenting population growth driving global warming, mass extinction

(06/26/2014) It took humans around 200,000 years to reach a global population of one billion. But, in two hundred years we’ve septupled that. In fact, over the last 40 years we’ve added an extra billion approximately every dozen years. And the United Nations predicts we’ll add another four billion—for a total of 11 billion—by century’s end.

‘Hope springs eternal’: the anniversary of the death of Lonesome George

(06/24/2014) Today marks the two-year anniversary of the death of Lonesome George, the world’s last Pinta Island tortoise. The occasion calls attention to the declines of many turtle and tortoise species, which together form one of the most swiftly disappearing groups of animals on the planet.

Broken promises no more? Signs Sabah may finally uphold commitment on wildlife corridors

(06/23/2014) Five years ago an unlikely meeting was held in the Malaysian state of Sabah to discuss how to save wildlife amid worsening forest fragmentation. Although the meeting brought together longtime adversaries—conservationists and the palm oil industry—it appeared at the time to build new relationships and even point toward a way forward for Sabah’s embattled forests.

Newly discovered snails at risk of extinction

(06/03/2014) A team of Dutch and Malaysian scientists has recently completed one part of a taxonomic revision of Plectostoma, a genus of tiny land snails in Southeast Asia. Unfortunately, according to their article published recently in ZooKeys, it seems that these animals may be going extinct as fast as they are being discovered.

Extinction rates are 1,000x the background rate, but it’s not all gloomy

(05/29/2014) Current extinction rates are at the high end of past predictions, according to a new paper published today in Science, however conservation efforts combined with new technologies could make a big difference. New research led by Stuart Pimm of Duke University argues that humans have pushed the current extinction rate to 1,000 times the historical rate.

(05/19/2014) A quiet zoo revolution has also been occurring over the past twenty-five years. Rather than just stand by the sidelines as species vanish in the wild, many zoos have begun funding on-the-ground conservation efforts. This revolution signals a widening realization by zoos of the positive—and wholly unique—role they could play in combating global mass extinction. But are zoos doing enough?

Scientists uncover new marine mammal genus, represented by single endangered species

.150.jpg)

(05/14/2014) This is the story of three seals: the Caribbean, the Hawaiian, and the Mediterranean monk seals. Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands, the Caribbean monk seal was a hugely abundant marine mammal found across the Caribbean, and even recorded by Christopher Columbus during his second voyage, whose men killed several for food.

Long lives, big impacts: human life expectancy linked to extinctions

(04/15/2014) Since the arrival of Homo sapiens, other species have been going extinct at an unprecedented rate. Most scientists now agree that extinction rates are between 100 and 1000 times greater than before humans existed. Working out what is driving these extinctions is fiendishly complicated, but a new study suggests that human life expectancy may be partly to blame.