Oil palm plantations cannot sustain orangutan populations in the long-term

One of humans’ closest relatives, the charismatic orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), has been listed as Endangered by the IUCN since 1986 and its status continues to remain critical. The orangutan population decline on the island Borneo can be attributed to extensive habitat loss caused by agricultural development, in particular, the palm oil industry. As oil palm plantations continue to expand to satisfy the ever-increasing global demand, orangutans and other wildlife are threatened by devestating habitat loss.

In a recent study headed by Dr. Marc Ancrenaz from Borneo Future and Dr. Isabelle Lackman, president of HUTAN-Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Project, researchers assessed how orangutans have adapted to living among oil palm plantations on Borneo. They focused their study on eastern Sabah in Malaysian Borneo, where land conversion for agriculture has left a mosaic landscape of agricultural land interspersed with fragmented patches of protected and unprotected natural forests.

Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) have declined 50 percent over the past 60 years. Photo by WWF.

As described in their recently published study in the Cambridge Journal, the researchers found that while orangutans have adapted to the island’s human-transformed landscapes better than expected, oil palm plantations are unable to sustain orangutan populations in the long-term. The researchers observed evidence of orangutans inhabiting small forest patches scattered among oil palm estates, but also observed evidence of starvation among those orangutans, as well as increased conflicts with humans.

“Whenever a forest occupied by orangutans is converted to a plantation (not only for palms, but also for paper pulp – acacias, eucalyptus – or some timber species), we can expect conflicts to happen,” Ancrenaz told mongabay.com.

Forest destruction for agriculture presents several challenges for orangutans during the different stages of land conversion, from the establishment of a new plantation to the maturation of cultivated land.

When a forest is newly converted for agricultural use, orangutans and other wildlife lose not only a place to live, but also access to vital food sources. During the land conversion process, animals are either killed or take refuge in neighboring patches of intact forest. However, these small forest patches often become overcrowded and cannot produce enough food to support the new influx of animals. Therefore, some of the animals venture into the cultivated land and feed on young palms, which is highly destructive for the plants. Between the ages of six months and three years, young palms are very sensitive to wildlife disturbance. When orangutans pull out and eat young shoots, they kill the plants and may cause significant economic losses for the land owners.

Over time, the situation stabilizes as the palm plantations mature and orangutan populations in the forests decrease because there is no longer enough food to support them all. At this point, many orangutans move back and forth between the forest and the edges of mature oil palm plantations. They can build nests in the palms and feed on the mature tree’s young shoots and fruit without causing harm to the tree’s productivity. However, some individuals travel deeper into the plantations, especially males when searching for mates or establishing territories. The further orangutans travel into plantations, the more likely they will be exposed to threats such as lethal encounters with dogs or people, and may be harassed and killed. They are also more vulnerable to the introduction of new diseases not found in the natural forest.

An oil palm plantation in Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Prompted by increased local observations of orangutans in oil palm plantations, the HUTAN-Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Project and Sabah Wildlife Department began conducting surveys in 2008 to assess the status of orangutan populations in oil palm plantations and natural forests of the Kinabatangan region. The researchers conducted both aerial and on-the-ground observational studies of orangutan populations in the Kinabatangan River floodplain region located in eastern Sabah, Malaysian Borneo.

From aerial surveys, the researchers observed the presence of orangutans throughout the fragmented landscape of forest patches and oil palm plantations in the entire lower Kinabatangan region. Because of their elusive natures, orangutan presence was determined based on sightings of nests, which the animals construct out of broken leaves every evening in the centers of treetops.

From ground surveys, the researchers recorded the presence of orangutans in oil palm plantations based on nest sightings as well as half-eaten fruit litter. The researchers observed orangutans eating young shoots and picking ripe fruit from the palm trees or off the ground. Orangutans prefer to nest in non-oil palm trees such as nipah palms (Nypa fruticans) or taller trees (Rhizophora sp., Bruguiera sp., Intsiapalembanica).

Orangutans are predominately arboreal creatures, spending most of their lives in the tree canopies where they build sleeping nests and search for food. The primates are highly adapted to canopy life and rarely travel to the forest floor where walking is an awkward and slow process. Orangutans are able to travel agilely through treetops where they can find all their necessary food sources of fruit, vegetation, and insects.

The distance that orangutans must travel to find food depends on the quality and size of a forest; if the forest produces a sufficient amount of vegetation and fruit to support its inhabitants, then they do not have to travel far to find food. The researchers found that orangutans in the Kinabatangan region did not have to roam over long distances to find food. The degraded forests of Kinabatangan were regenerating new growth of vines and various plant and tree species that offered a continuation of young leaves, as well as fig trees that produced fruit most of the year.

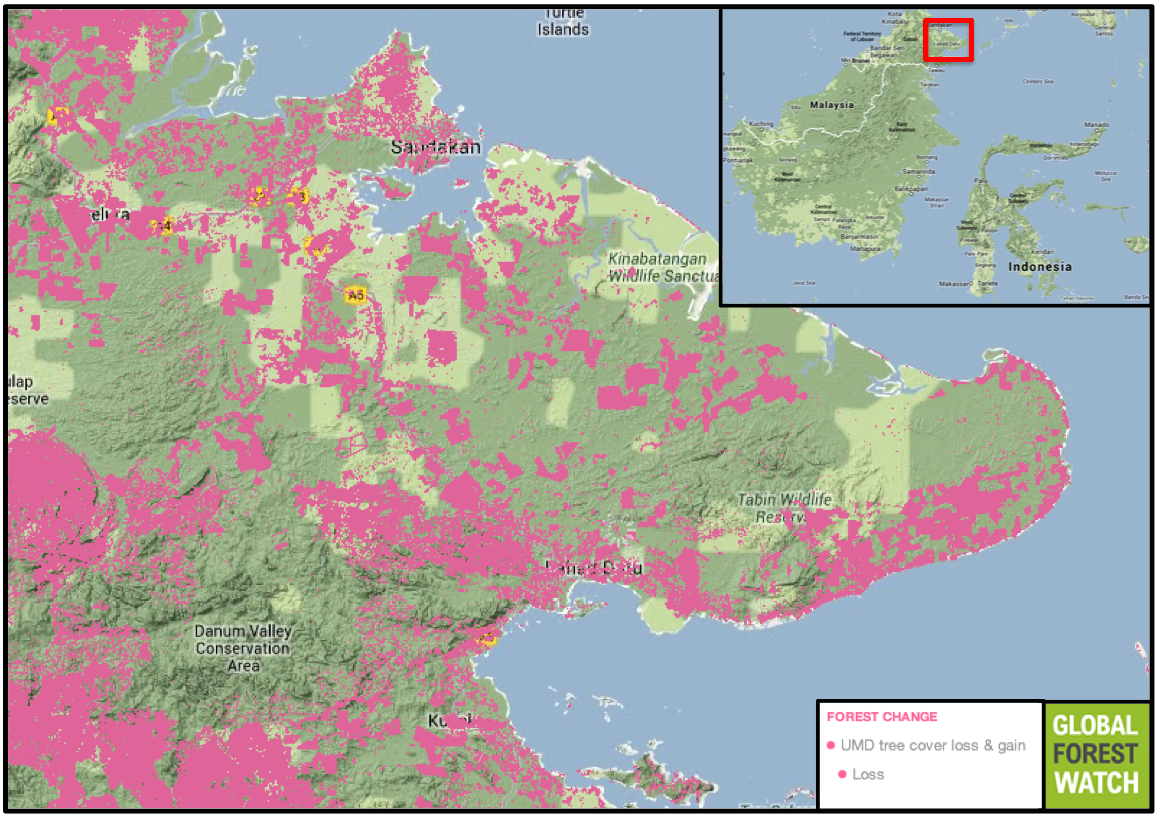

According to data from Global Forest Watch (GFW), the Kinabatangan region of Borneo has lost more than 15 percent of its forest cover over the last 14 years. Map courtesy of GFW. Click to enlarge.

However, in some situations, forest patches are too small to produce enough food throughout the year. This may mean starvation for many animals, and others may have to relocate in order to find enough food – sometimes to oil palm plantations.

However, the food sources found in oil palm plantations are not as nutritional as a wild diet, and may not be enough for orangutan survival in the long-term.

“Orangutans need a very diverse diet to survive,” Ancrenaz explained. “In the forest of Kinabatangan, wild orangutans feed on more than 300 plant species. Relying on only a single species of plants (palm fruit) to survive would be equivalent to people feeding only on carrots, for example. This is not healthy. Agro-industrial oil palm landscapes are not a proper habitat for the orangutan species. This landscape needs more plant diversity to sustain orangutans.”

Increased land conversion of forests into oil palm plantations is also leading to an escalation in conflicts between humans and orangutans. Although they rarely travel on the forest floor in a natural environment, the researchers observed an increase in orangutan activity on the ground in areas impacted by oil palm development. Orangutans were often seen walking across oil palm plantations, roads, and open areas when disturbed by humans. On the ground, orangutans are able to move quieter compared to rustling through the palm fronds when traveling through the trees. The researchers believe this is a behavioral adaptation to living in a human-inhabiated and changed areas where it’s important for them to travel through oil palm plantations undetected.

In addition to observational surveys, the researchers conducted interviews with oil palm workers in the lower Kinabatangan region. The researchers found an unexpectedly high encounter rate between the plantation workers and orangutans within the industrial agricultural landscape, indicating increased orangutan activity in plantations.

“Most of the people interviewed during our surveys are afraid of the orangutans and will walk away from the animals,” Ancrenaz said. “However, when orangutans repeatedly raid people’s crops (especially local orchards) the crop owners tend to look at them as pests and try to scare the animals away, to request assistance from relevant authorities to translocate them, or to kill them.”

New oil palm plantation cleared from peat forest in Indonesia’s Central Kalimantan Province in 2013. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Orangutans are protected species in Indonesia and Malaysia and it is illegal to hurt, harass, or kill them. However, many locals still hunt orangutans for food.

This study provides new information for future orangutan conservation. However, further research is needed to assess the full impact of the industrial agricultural landscape on orangutan populations in the long-term.

In the 1960s, prior to the introduction of oil palm agriculture, when forests still densely covered the landscape, over 4,000 orangutans lived within the lower Kinabatangan region. Today only an estimated 800 orangutans remain in the region. Genetic analysis has shown that the population has declined more than 95 percent over the past 100 years. The researchers believe that the orangutans observed during their study are part of the original population.

“The future [existence] of orangutan populations that are living in landscapes fragmented and fractured by oil palm plantations, such as in the Kinabatangan, depend on how the oil palm industry is going to ensure a functional connectivity between isolated forest patches that are inhabited by orangutans,” Ancrenaz said. “If we fail to re-establish this connectivity, the orangutan population in Kinabatangan is going to keep on declining until oblivion.”

These research findings highlight the inability of oil palm plantations to sustain orangutan populations and emphasizes the importance of protecting remaining forested areas.

“Protection of forested areas within plantations is crucial to alleviate the problem of forest fragmentation for the orangutan as well as other wildlife such as the Bornean elephant and clouded leopard,” said Ancrenaz. “This will allow for these animals to safely move through and promote viable (healthy, productive, genetically diverse) populations in the state – a win-win situation for sustainable forestry, oil palm industry and tourism.”

Citations:

- Ancrenaz, Marc, et. al. “ Of Pongo, palms and perceptions: a multidisciplinary assessment of Bornean orang-utans Pongo pygmaeus in an oil palm context.” Cambridge Journal. 2014. 10.1017.

Related articles

Stolen fruit may spur better palm oil traceability(06/16/2014) Rising theft may improve traceability in Malaysia’s palm oil industry.

Despite green pledge, Wilmar partner continues to destroy forest for palm oil

(06/12/2014) Two palm oil companies partially owned by Wilmar are continuing to destroy rainforests in Indonesia despite a high profile zero deforestation pledge, alleges a new report published by Greenomics.

National doughnut chains contributing to rainforest destruction, says report

(06/06/2014) Activists have leveraged National Doughnut Day to call to major chains on their palm oil sourcing policies. Forest Heroes and SumOfUs say some of America’s largest doughnut companies are contributing to the destruction of tropical rainforests by purchasing palm oil with little regard for its origin.

Greenpeace rates companies’ zero deforestation commitments

(06/06/2014) Greenpeace has released a basic rating system to gauge the strength of companies’ zero deforestation commitments related to palm oil sourcing.

RSPO plantations publicly mapped for the first time

(06/04/2014) A global map of the world’s Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certified oil palm plantations is available for the first time.

Philippines targets 8M ha for palm oil production

(06/04/2014) The Philippines is proposing to convert 8 million hectares (20 million acres) of ‘idle, denuded and unproductive lands’ for oil palm plantations, reports the Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Greenpeace accuses controversial palm oil company and Cameroon government of illegal logging

(05/28/2014) Greenpeace has just accused one of the world’s most controversial oil palm companies, Herakles Farms, of colluding with top government officials to sell off illegally logged timber to China. According to a new report, an agreement between Cameroon’s Minister of Forestry and Herkales Farms—through a shell company—could torpedo the country’s agreement with the EU for better timber management.

Indonesia’s haze from forest fires kills 110,000 people per year

(05/28/2014) Haze caused by burning peat forests in Indonesia kills an average of 110,000 people per year and up to 300,000 during el Niño events, while releasing hundreds of millions of tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, warns a new report from Greenpeace. Sumatra: Going up in smoke argues that peatland and forest protection are the best way to protect the region from the effects of haze.