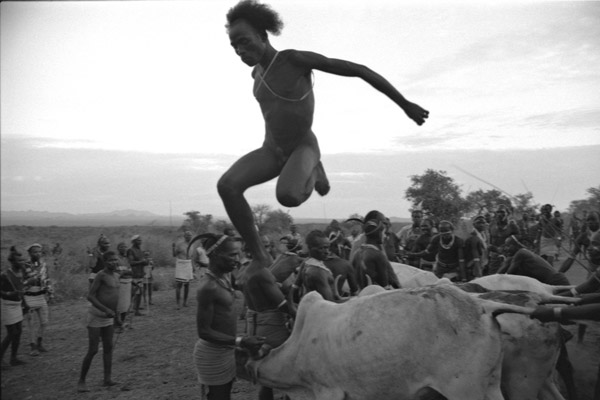

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson.

Ten years ago, Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson photographed and wrote Lost Africa: The Eyes of Origin, a tribute to the expansive imagination of Africa’s vast landscape, incredible people, and astonishing animals. As Marie and Cyril tell us below in this interview, now is the time to listen, consider, and conserve our ecology and our cultural relationships with the ecology that supports us each day.

Through the clarity of the lens, Lost Africa: The Eyes of Origin introduces us to remarkable individuals whose lives have certainly changed ten years hence. In the book we are we are rhetorically asked what is culture, how do we preserve and celebrate culture, and change with culture while conserving the ecosystems we depend on?

Since 1997, husband and wife team, Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson have been investigating and documenting the relationship between the Indigenous Peoples and natural world on five continents. Lost Africa: The Eyes of Origin, which also placed in the fine art book category at the International Photography Awards in 2008, explores the ecological and man-made challenges facing tribes from Ethiopia to Namibia. A more recent book, Walking Thunder: In the Footsteps of the African Elephant, is one of the first manifestos in black and white ever dedicated to a single species in the wild. It placed in the Nature book category at the International Photography Awards in 2010. As filmmakers, their documentary dedicated to the elephant The Last Stand of the African Elephant is narrated by Ali McGraw and is available on YouTube. Currently, they are working on a feature documentary with their young son Lysander called Walking Thunder: The Last Stand of the African Elephant. Cyril Christo is an Oscar-nominated filmmaker whose film A Stitch for Time—an anti-nuclear documentary— was nominated for an Academy Award in 1988.

INTERVIEW WITH CYRIL CHRISTO

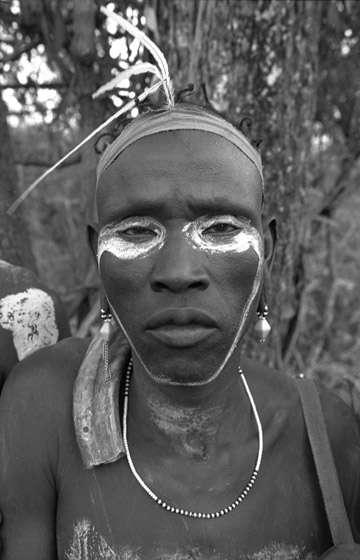

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson.

Mongabay: What local conservation trends have you noticed in the past ten years in Africa?

Cyril Christo: Any successful initiative to help the wildlife must include the African people and issues of overpopulation, human encroachment in protected areas and climate change. The Community Based Natural Resource Management in Namibia has 50 communal conservancies entrusting 15 percent of the country’s land to Indigenous Peoples. When we walked among black rhino on foot in Kaokeveld over ten years ago, this program was in full force and is one of the great victories of conservation. Everything has to be predicated on the needs of the African people in tandem with the wildlife.

Foreign decisions like CITES decision in 2008 to let China and Japan buy 100 tons of southern African countries was a catastrophe and just incited the illegal ivory trade which has also impacted local Africans across the continent. It will take a real concerted global effort to save the rhino and elephant and consign the ivory trade to the dustbin of history. But ultimately it will be up to Africa to save its precious wildlife.

There have been major initiatives to open up such unique wildlife corridors as the Kavongo Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area linking Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The recently established Namib Skeleton National Park in Namibia is the 8th largest protected area on earth, which is welcome. But let us not forget that thousands of Cape Cross fur seals were yearly destroyed. Is this the best wildlife practice humanity is capable of? Or are these conservation areas in name only? The seals are not a menace to the fish in the Atlantic, people are. One can designate a National Park but then let us act as if these areas were a true sanctuary and not just a reserve in name only.

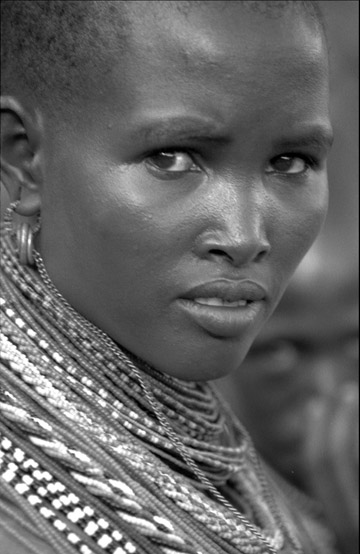

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson. |

Often it has felt as if conservation and globalization were on opposite sides of the psychic spectrum. Bernhard Grizmek in Serengeti Shall Not Die wrote “Men are easily inspired by human ideas, but they forget them again just as quickly. Only Nature is eternal, unless we senselessly destroy it. In fifty years’ time nobody will be interested in the results of the conferences which fill today’s headlines. But when, fifty years from now, a lion walks into the red dawn and roars resoundingly, it will mean something to people and quicken their hearts whether they are bolshevists or democrats, or whether they speak English, German, Russian or Swahili.”

The discrepancy between the conservation and the dictates of globalization has long term effects on Africa’s Indigenous Peoples and wildlife. This has become most evident in the last decade. The marginalization of Africa’s Indigenous Peoples, we were first concerned about with Lost Africa, has long term consequences on the future of wildlife and conservation. While Tanzania has treasures beyond compare, why have the Maasai in the Loliondo region been moved off their land, their biomes burned for the private hunting practices and amusement of the sheikhs of the United Arab Emirates? The Maasai never threatened their wildlife like outsiders do today and never merely for entertainment. They do not do canned hunts and mercilessly shoot innocent beings for mere fun. That is morally depraved. Do profits really outweigh the essential irreplaceability of the ecosystem of East Africa and the continent as a whole? One Maasai elder, Paramitoro Ole Kasiaro, we met on the way to the Serengeti years ago, once said, “The Maasai had a tradition that protected the environment and the wildlife. Maasai believe that if a man kills too many lions he will be cursed.”

Does a great treasure of the Serengeti need a highway around it, never-mind through it? Does the Selous need uranium mining operations when almost 90% of its elephants have been lost due to poaching? Does a massive port in Lamu on the Indian Ocean really benefit the marine eco-system there? It is all done in the name of globalization and it is a desecration. It is not a question of not telling Africans what they should or should not do. It is a question of survival for the ecology of the planet. Without an environment there is no viable economy.

The Ogiek/Ndorobo of western Kenya, one of oldest peoples in Kenya have been evicted from the Mau forest: they are victims of resettlement programs and human rights violations. They are now living in squalor. The Ndorobo have followed the migration paths of elephants for centuries. They told us of the olden days when elephants used to live peacefully alongside humans. They would eat the olerondo fruit in imitation of elephants and boil acacia bark for its sugar.

Tales of being given milk from elephant cows in times in drought are mythic.

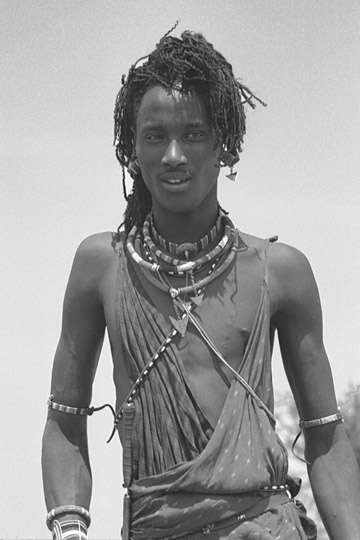

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson. |

The Ndorobo supposedly gave elephants honey to help them survive in times of drought and elephants would help people find water. These stories are essential part of their lore but they have a basis in survival. These hunter- gatherer peoples cannot be forgotten. They form the core of our beginnings.

In Botswana, the San Bushmen faced similar evictions, not for forest land but for the diamond kimberlite pipes under their land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. One of the oldest continuous genetic groups on Earth had become squatters in New Xade, a bleak settlement place of desperation. When the government of Botswana says they are concerned for the wildlife, they really mean they are after the diamonds which have enriched Botswana but not its Indigenous Peoples. When Roy Sesana, the head of the First Peoples of the Kalahari says, “We are the diamonds of the desert”, he means it. Their knowledge and respect for the land, rain, and wildlife is unsurpassed. The Bushmen who were made first, “have come to be last, and those who were created last have come to be first.” Many have voiced their concern that they had to be separated from their brother, the lion. In light of lion conservation which is critical today in Africa, the truce the Bushmen have with the greatest predator in Africa should be paramount in conservationist’s minds. Lions have lost 90 percent of their population in the last generation. And no-one on earth knows lions better than the Bushmen.

In Namibia, the Himba are the pre-eminent pastoralists of southwest Africa. We were concerned with the potential dam on the Kunene River over 15 years ago but the big dam today is in Ethiopia which menaces tens of thousands of tribal people from the Hamar, Karo, Surma and Mursi people and many others. Do they too have to be sacrificed to the moloch of modernity? For electricity, for money, for power.

“Big Dams are to a nation’s ‘development’ what nuclear bombs are to its military arsenal,” writes Arundhati Roy.

It is the same problem in the Amazon, America, Canada, India, China, Southeast Asia, the world. Ironically, pastoralists in Africa who have the greatest survivalist ethos, become the sacrificial lambs of the modern state. David Western who has worked with the Maasai is noted to have said, “The reason wildlife has been preserved is because of the pastoralists.”

In northern Kenya, among the Turkana, we saw a fiercely proud pastoralist people become fishermen. The government with help of an NGO from Norway helped construct a fish factory which did not succeed. Only far too late was it realized that the Turkana themselves consider fishing the last resort of those who cannot tend to their cows. The derelict body of the fish packing plant lay like the carcass of modern folly stranded on the sands of an exhausted land. A formally self- sufficient people became dependent on government subsidies. This same equation has happened to Indigenous Peoples all over the planet. What ensues is sedentarism and the loss of the forest canopy. Tribal peoples and animals both suffer. Then the droughts come and the wildlife evaporates. If we took the time to listen and honor the Indigenous Peoples of the world, we would have a different planet.” One elder told us: “In the old days, there was always rain and the Turkana lived peacefully. Now there’s a drought because God is angry because of the amount of blood that has been spilled, because of intertribal battles.”

The overall perspective has never been stated better than by Alistair Graham from Eyelids of Morning:

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson. |

“It seems to be the destiny of all Walden Ponds, Lake Rudolf included, to be consumed by technological man. It is not for the Turkana to say yea or nay. He does not even have to submit or flee. He will not be butchered for his balkiness or haughtiness, as the Indian was. Instead he will be inundated with benevolence. Sociological, religious, political, economic, scientific, medical and technological benevolence. It is monstrous, really, the technological impertinence of industrial man that supposes he is in command of nature, capable of ordering the destinies of all things.”

Mirella Ricciardi (the author of Vanishing Africa (1971) gifted us with a quote for Lost Africa:

“Until Africa finds her 21st century identity, until her new form emerges, her people and her land will first have to pass through the birth pains of purgatory. The agony will last as long as is needed. In the confusion and disorientation of readjustment, humans and wildlife will lose their direction, many will perish, the earth will be badly damaged, and those who survive will be changed forever. There will be no going back.”

Mongabay: How are East African society youth becoming engaged in conservation?

Cyril Christo: Game warden Wilfred Ngonze from Satao Elerai camp in Kenya writes: “The East African wildlife society, which operates within the East African region, has been running conservation programs for the youth in the region. In Kenya, Wildlife Clubs of Kenya (WCK) has increased conservation awareness targeting the youth in primary, secondary and tertiary institutes. Several universities are training wildlife managers, while Kenya Wildlife Services has established fully equipped wildlife conservation education centers in the popular parks, where the Kenyan youths are exposed to conservation programs in order to win their hearts. Locally, Satao Elerai Management connects the local youth with conservation through provision of educational support e.g. construction of school and awarding school bursaries to enable the youth to access education, which is the key to understand the values of conservation and hence support it. The youth therefore are well exposed and prepared for the future challenges, however, they will need more resources.”

Mongabay: Why did you write Lost Africa: The eyes of Origins? Why specifically Africa? Why focus on cultures and conservation?

Cyril Christo: Marie and I started looking at the issue of climate change in the southwest of the United States from the Indigenous Peoples’ perspective. We were originally concerned with coal and uranium extraction in New Mexico and Arizona, in Kakadu, in northern Australia, Tibet and southern Africa with the Bushmen back in 1998. We started seeing commonalities around the world due to the severe El Nino cycle that year, a year that saw many wildfires and increasing temperatures worldwide. The Hopi of Arizona have been talking about the coming time of purification (powateoni) for generations but few people in the dominant society listened and certainly not the media at large. We also examined the impact of the industrial society on the land. Mining for coal, uranium, gold or oil has had a deleterious impact on all these cultures. And the technological society continues to plunder native peoples all over the planet. Between the disasters of globalization and climate change, the world’s Indigenous Peoples have to fight an enormous battle to hold onto to their identity.

The mythic understanding of the aboriginals is apparent in their oral traditions and reverence of the Earth as a living being. It seems everywhere that has an oral tradition that is wondrous, that has huge ecological import is desecrated. What bioregions will be left to explore in twenty years time? What wilderness areas will the earth still harbor? What species will remain for children to wonder at?

We met an elder Big Bill Neidjie, in Kakadu who was born under a rock escarpment and when he spoke it was as if the trees and the stars were talking back to you. Which in subtle ways they are. But we have consigned the language of the world to mere ciphers, while forgetting that even in our civilization, seers like Wordsworth had an ecologically based understanding of the world. We heard testimonies from several elders about the dominant society in Australia and how they ransacked the outback. And now they are selling uranium to China while poisoning the land. The weather in Australia since we were last there has turned upside down with both the greatest heat waves ever recorded and the greatest floods. How can the politicians there ignore the evidence of climate upheaval? How can the current powers that be allow a coal port on the Great Barrier Reef, the greatest single coral gem on earth?

It was with the Bushmen of the Kalahari where lions still roam, that we started concentrating on Africa because it seemed the most startling and manifest place where the larger realities of human non- human interaction were most evident, where the creator and the destroyer aspects of Creation were ever-present manifestations. The Bushmen stories are among the most exquisite oral traditions ever recounted. And their allegiance to the larger realities like the stars, the trance dance in which medicine men climb the threads to God’s village, is utterly spell binding. Their knowledge goes back over 40,000 years. The beginnings of their society go back 2,000 generations. The hunter gather, pastoralist ethos of the people of east Africa is one of the greatest survivalist strategies ever devised, especially for surviving in arid areas. They were among the proudest and most self- sufficient people on earth.

Listening to the Turkana of northern Kenya or the Surma, Mursi or Hamar of Ethiopia about how the rains had changed in the 1980’s informed us that something crucial was changing in the world’s weather patterns. That rains in the earlier days were frequent and that even if they came they were not as strong as before. That has affected the wildlife. The human animal connection is also unmatched in Africa. When one connects the loss of elephants in northern Kenya with the recent droughts, one starts to see the larger pattern. When one hears stories by the camp fire and sees elephants parading in the distance one is spellbound! It is a primal experience unmatched on earth Except perhaps in Asia where elephants are still part of the local ecology and culture. They still haunt the modern imagination. The local peoples know and honor the elephant in ways that biologists do not.

Photograph © Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson. |

We are working on a feature documentary Walking Thunder that examines the Indigenous Peoples’ relation to the great monarch of the terrestrial world. The human- elephant bond is something we have forgotten as with the human- lion bond, as with all animals. It is at the core of all animist belief systems. It is not something our digitally fixated, algorithmically and technologically seduced civilization honors. We lose touch with our origins and the matrix of the organic world at our own peril. We have more to learn and benefit from those people who have been on the ground for millennia than the machine makers and their android fantasies over the next forty years. The Indigenous Peoples of the world are the ontological immune system of the planet, they know who they are, because they are living an authentic relationship to the soil and the soul. The dominant society does not and that is the basis of the climate crisis and our present relationship to the biosphere.

It was while we were at Amboseli, at the lovely Satao Elerai camp that we heard a remarkable story from a half Maasai, half Sikh guide. A few years ago we learned of a Kikuyu mother who gave birth in the wild, near Kilimanjaro with the help of a bull elephant! The story will be in our film. It was a revelation and one of the greatest stories of human non human interaction of all time. We had first heard of the bond between the Kikuyu in Amboseli when we were with Mike Rainy (who speaks the Maa language fluently) because he had been very taken by Louis Leakey’s understanding of the Kikuyu. According to the Kikuyu, people in the tribe often swore oaths and resolved conflicts in justice ceremonies with the aid of the atlas bone of an elephant, where all the major nerves run towards the head of the elephant. You cannot lie when making an oath. If you do bad karma ensues! There is a quasi mystical allegiance to the elephant, an alliance that the modern world, with the renewed ivory trade, dares to imperil. Perhaps the elephant and the Kikuyu woman had a bond for a reason. In any case, the ivory crisis is much larger than the future of the elephant. It is also about the future of the biosphere. What totems do we hold sacred? Why do we hold the machine in such high regard when life is so much more wondrous? At the time of Lost Africa we did not realize the great bond some tribes have with the elephant. And most of the world still does not realize it. We first made the world aware of the absolute menace of the ivory trade in the Agony and Ivory( August 2011) article in Vanity Fair (written by the eloquent Alex Shoumatoff) It galvanized the world! Now the planet knows what is at stake. The native people say there is a curse put on those who kill an elephant. Let us hope it is not a planetary curse and that we can stop the elephanticide. Our very sanity depends on it.

One of the wonderful concepts we learned from the Maa speakers, the Maasai and Samburu (Maa means to listen, to listen to the rain) is the idea that God is far but near (kela qua enkai eta na) and can be approached only through respect and prayer. The Maasai leap so that their spirit can grow tall like a tree! They do not have a separate concept for nature, as we do. Instead, they have a term enkope Ngai, which means the beauty of God, like the Dine (Navajo) whose essential belief system is to walk in beauty. The pastoralist ethos is based on an all abiding respect for earth’s capacities for renewal; real wealth is regenerative while ours is about plundering, polluting and desecrating. Our civilization by comparison, both the communist and capitalist system does not have a leg to stand on. It is based on greed. Few people in the market economy have listened to EF Schumacher and his masterpiece Small is Beautiful. He has been made into an outcast. The capitalist system and the Indigenous Peoples of the world have completely opposite philosophies. Witness the Bishnois of India who do not even dare cut down trees. The Maasai honor the great fig trees. What do we do? We evict them from Ngorongoro crater. For both the pastoralists and hunter- gatherers in Africa and all over the world, true power derives from the capacity to grant a knowledge of the earth’s gifts to the next generation. The dominant technological society is stealing the life force from the next generation. It is a sin beyond reckoning.

The next five years are absolutely crucial to the biosphere. We have heard from the Dine in the American Southwest that we have until 2020 to turn things around. In the words of the great historian Arnold Toynbee, “Shall we murder Mother Earth, or shall we redeem her?” Part of the answer lies with Indigenous Peoples of the planet, those who still have a cosmology that honors existence! The world, the powers that be, the bankers, and politicians and technocrats have to decide if they really love their children or if they have a greater love for money. All the ecological violations executed in the name of profit have also been human rights violations with regard to Indigenous Peoples everywhere. In Africa, the climate within and the climate without serves as a unique template for humanity’s relationship to the elemental realities, to the roots of our relationship with the earth, and her inimitable wildlife, without which we cease to be human!

Africa stands as the shadow of our beginnings, cradle to humanity, and the great mirror to what we are in the process of becoming, a thirsting purgatory caught between origin and our common fate. We have a quote in Lost Africa from a rather prescient artist, but also one who is also a seer, an inventor, a man who adored the natural world and who understood that without a reverence for the natural world, humanity has nothing, a man who knew that humans were not superior to animals. In his Prophecies Leonardo da Vinci wrote,” All men shall find refuge in Africa.” How could he have known?

Laurens van der Post talked about the great imponderables in oneself. Africa teaches us something about our origin that is unique on earth. That is why we entitled our book The Eyes of Origin.

“Modern man with his grievous and crippling realization of having lost the sense of his own beginnings, with his agonizing feeling of great and growing estrangement from nature, finds that life holds up Africa like a magic mirror miraculously preserved before his darkening eyes.” We must preserve what is left of that magical mirror.

How to order:

Paperback:Lost Africa: The Eyes of Origin

Publisher: Assouline

ISBN: 9782843236075

Authors: Cyril Christo & Marie Wilkinson

Gabriel Thoumi, CFA is a Sr. Sustainability Analyst at Calvert Investments and a frequent contributor to Mongabay.com.

Medard Masangu is from Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. He studies Film Media Arts and Marketing at American University, Washington, DC.

Related articles

Study warns of possible REDD+ land grab

(03/30/2014) A UN program to reduce global carbon emissions may be putting indigenous communities at risk, jeopardizing local land rights and laying the groundwork for large-scale “carbon grabs” by governments and private investors, argues a new report.

Indigenous communities demand forest rights, blame land grabs for failure to curb deforestation

(03/25/2014) Indigenous and forest-dependent peoples from Asia, Africa and Latin America have called for increased recognition of customary land rights in order to curb deforestation and ensure the survival of their communities. The Palangkaraya Declaration on Deforestation and the Rights of Forest Peoples calls on governments to uphold forest peoples’ rights to control and manage their customary lands and to halt rights-violating development projects being carried out without consent from local communities.

Indigenous people witness climate change in the Congo Rainforest

(03/20/2014) Indigenous communities in the Republic of Congo are observing climate change even though they have no knowledge of the science, according to a unique collaboration between the Rainforest Foundation UK (RFUK) and local communities. The environmental changes witnessed by the locals in the Congo rainforest include increased temperature, less rainfall and alterations to the seasons, much as expected under global climate change.

Oil or rainforest: new website highlights the plight of Yasuni National Park

(03/20/2014) A new multimedia feature story by Brazilian environmental news group, ((o))eco, highlights the ongoing debate over Yasuni National Park in Ecuador, arguably the most biodiverse place on the planet.

Featured video: indigenous tribe faces loggers, ranchers, and murder in bid to save their forests

(03/19/2014) A new short film, entitled La Trocha, highlights the plight of the Wounaan people in Panama, who are fighting for legal rights to their forests even as loggers and ranchers carve it up. The conflict turned violent in 2012 when local chief, Aquilo Puchicama, was shot dead by loggers.

Mother of God: meet the 26 year old Indiana Jones of the Amazon, Paul Rosolie

(03/17/2014) Not yet 30, Paul Rosolie has already lived a life that most would only dare dream of—or have nightmares over, depending on one’s constitution. With the Western Amazon as his panorama, Rosolie has faced off jaguars, wrestled anacondas, explored a floating forest, mentored with indigenous people, been stricken by tropical disease, traveled with poachers, and hand-reared a baby anteater. It’s no wonder that at the ripe age of 26, Rosolie was already written a memoir: Mother of God.

Indonesian sugar company poised to destroy half of island paradise’s forests

(03/14/2014) An Indonesian plantation company may be preparing to destroy up to half of the natural forests on Indonesia’s remote Aru Islands, reports Forest Watch Indonesia. Analyzing land use plans for Aru, Forest Watch Indonesia found that local government officials have turned over 480,000 hectares (1.2 million acres) to 28 companies held by PT. Menara Group, a plantation conglomerate. 76 percent of the area is currently natural forest. Converting the area to sugar plantations would cut Aru’s forest cover by half, from 730,000 ha to 365,000 ha.

New web tool aims to help indigenous groups protect forests and navigate REDD+

(03/12/2014) A new online tool, dubbed ForestDefender, aims to help indigenous people understand and implement their rights in regard to forests. The database, developed by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), brings together vast amounts of legal information—both national and international—on over 50 countries.

Cocaine: the new face of deforestation in Central America

(03/11/2014) In 2006, Mexico intensified its security strategy, forming an inhospitable environment for drug trafficking organizations (also known as DTOs) within the nation. The drug cartels responded by creating new trade routes along the border of Guatemala and Honduras. Soon shipments of cocaine from South America began to flow through the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor (MBC). This multi-national swathe of forest, encompassing several national parks and protected areas, was originally created to protect endangered species, such as Baird’s Tapir (Tapirus bairdii) and jaguar (Panthera onca), as well as the world’s second largest coral reef. Today, its future hinges on the world’s drug producers and consumers.