The successful end of a monkey hunt by an indigenous tribe in Suriname results in a howler monkey for dinner. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

The barbecued leg of a spider monkey might not be your idea of a sumptuous dinner, but to the Matsés or one of the fifteen tribes in voluntary isolation in Peru, it is the result of a successful hunt and a proud moment for the hunter’s family. However, a spider monkey tends to have only a single infant once every 30 months, which necessarily limits the number of adult monkeys available to subsistence hunters.

If hunting is to be sustainable, a delicate balance must be maintained between a monkey’s ability to replace those that are hunted, and a hunter’s ability to selectively extract monkeys for food. Unfortunately, this fragile connection has been repeatedly shattered across Amazonia: in these areas, it is the diminutive monkeys, like the squirrel-sized tamarin, that now dominate the Amazonian landscape, creating cascading disadvantages for forest growth and regeneration.

From May to August of 2011, Cooper Rosin, a doctoral student from the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, set out to collect information on primates that were preferentially hunted for subsistence across the Amazon basin. His work, conducted in conjunction with Varun Swamy, a 2012-13 Bullard Fellow in Forest Research at Harvard Forest, focused on gathering detailed census information on primates, large and small, from variably hunted sites in the Peruvian Amazon rainforest.

Saddleback tamarins, the smallest primates in the forest (weighing less than one pound), at the Los Amigos Biological Station. Photo by: PrimatesPeru. |

“Early results from seedfall traps and census plots had shown that seed movement and tree regeneration were being impacted along a gradient of hunting intensities,” Rosin told mongabay.com

Just as we exert choice over what constitutes a worthwhile dinner, it appears that subsistence hunters in the Amazon also prefer some monkeys to others.

“When people hunt [primates],” explained Rosin, “it is the frugivorous species—especially large ones—that often bear the greatest burden.”

These species—including spider monkeys (Ateles spp.), howler monkeys (Allouatta spp), and woolly monkeys (Lagothrix spp.) —generally weigh over 20 lbs each and are slow to reproduce: they breed seasonally, typically only once every 30 months, and have a single offspring that require long periods of nursing and care before their mothers can breed again. In contrast, tamarins and marmosets (of the family Callitrichidae), weigh less than a pound, and can proliferate faster. This inherent size difference also means that a given forest can sustain many little tamarins for every large woolly monkey.

Most importantly, small monkeys make small targets. In the eyes of a hunter, small monkeys provide rewards that are too low, given the effort that must be expended to capture them. Rosin and Swamy’s research, published recently in the journal Neotropical Primates (see here for Rosin’s original thesis), has shown that small monkeys in hunted forests exhibit compensatory growth in the absence of larger primates. In other words, when larger monkeys are removed, population densities of small monkeys can skyrocket.

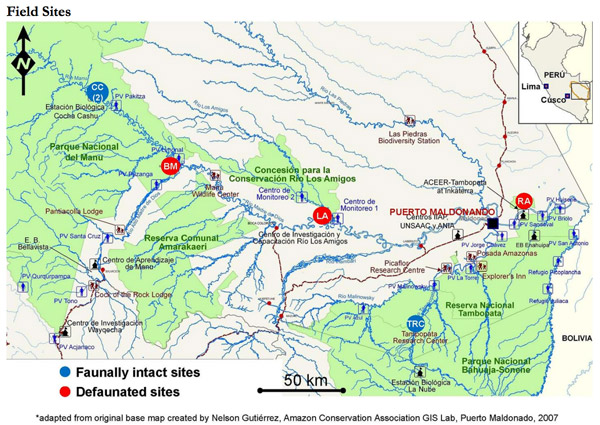

Field sites in the Madre de Dios river basin. Faunally intact site used in this study: TRC (Tambopata Research Center). Defaunated sites (with loss of large primates) used in this study: LA (Los Amigos) and RA (Reserva Amazónica). Figure adapted from Rosin, 2012. Click to enlarge.

Rosin and Swamy studied the primate populations at three sites that were subjected to varying levels of human hunting pressure: the nearly pristine Tambopata Research Center (TRC) (50 km from the nearest humans), the previously hunted but currently protected Los Amigos Biological Field Station (LA) (2 km from humans) and the Reserva Amazonica (RA), surrounded by land utilized heavily by humans. In total, the researchers and their assistants surveyed 305 km for primates, roughly a hundred kilometers in each site.

At the most heavily hunted site RA, the researchers found smaller primates in densities over five times higher than in the least hunted site (TRC). This supported the idea that the population densities of small monkeys, in the absence of large ones, had increased greatly in a phenomenon called ‘compensatory growth’.

The primary ecological concern that arises in light of this phenomenon, aside from the obvious disadvantages faced by larger monkeys, is that the composition of the vertebrate population itself becomes disrupted, with cascading effects that can be felt for decades.

“The result,” said Rosin, “is a major re-organization of community structure and primate biomass in hunted tropical forests. For primates this means that large-seeded trees may face dispersal failure, while the dispersal of seeds from small fruits can actually increase.”

Thus, the forests themselves, which are so reliant on frugivorous primates for seed dispersal, are now at risk.

There is compelling evidence from other sites in the Amazon of the long-term effects of hunting. At the Cocha Cashu Biological Field Station nestled within Manu National Park, spider monkeys were surveyed first in 1988 and then once more, 20 years later. An increase of 55 percent (77 to 119 individuals) was observed to have occurred during that time. Since Manu National Park received official protection in 1973, according to Rosin, “it is likely that these populations were still recovering from local hunting pressure during the rubber boom at the turn of the 20th century, more than 75 years prior to Symington’s survey [in 1988].”

Can monkeys be sustainably hunted?

Howler monkeys, commonly one of the first primates to be extirpated in hunted forests, photographed at Cocha Cashu Biological Station. Photo by: Varun Swamy.

Assessments show that a tropical forest has a maximum capacity of one person per square kilometer that can be dependent exclusively on wildlife for protein, but human populations that hunt nearly always surpass this limit. However, where there is immigration of animals from nearby unhunted populations, subsistence hunting may be sustainable in specific locations.

“The technology used is a major factor,” Swamy explained to mongabay.com. “Bow and arrow hunting is more sustainable than hunting with shotguns, because of its comparative inefficiency and the total effort required. Access to motorized transportation and proximity to roads also dramatically changes the equation.”

Rosin suggests that shifting hunting towards species with higher reproductive output could also alleviate hunting pressures on slow-reproducing primates.

“Ultimately, many conservation initiatives will have to be more holistic,” he said, “combining biodiversity-based approaches such as education, land use planning and hunting restrictions, with food-based ones, like improved domestic animal husbandry, veterinary care and agricultural advances.”

The future, according to Rosin, is still an optimistic one. “It is easy to be doom-and-gloom about conservation, and there are very good reasons for concern,” he says,” but ultimately there are bound to be viable solutions.”

The Common woolly monkey is one of the larger-bodied primates in the Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

A table of density-estimates generated by the program ‘Distance’ of small, medium and large primate species and population-level effects of hunting at three sites. Adapted from Rosin, 2012.

Citations:

- Rosin, C. 2012. Assessing vertebrate abundance and the effects of anthropogenic disturbance on tropical forest dynamics. Master’s Thesis. Duke University

- Rosin, C. and Swamy, V. 2013. Variable density responses of primate communities to hunting pressure in a western Amazonian river basin. Neotropical Primates 20 (1): 25-31

- Robinson, J.G. and E.L. Bennett. 2000. Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests. Columbia University Press

- Symington, M.M.F. 1988. Demography, ranging patterns, and activity budgets of black spider monkeys (Ateles paniscus chamek) in the Manu National Park, Peru. American Journal of Primatology 15: 4567

Related articles

Will yellow fever drive brown howler monkeys to extinction in Argentina?

(04/04/2014) The brown howler monkey is listed as Critically Endangered in Argentina, where a small number persist in the northeastern portion of the country. Although habitat loss and other human impacts have contributed to the populations’ decline, a new report indicates that yellow fever outbreaks in the region are primarily to blame.

Over 9,000 primates killed for single bushmeat market in West Africa every year

(03/24/2014) Over the past 25 years, West Africa’s primates have been put at risk due to an escalating bushmeat trade compounded with forest loss from expanding human populations. In fact, many endemic primates in the Upper Guinea forests of Liberia and Ivory Coast have been pushed to the verge of extinction. To better understand what’s happening, a recent study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science investigated the bushmeat exchange between these neighboring countries.

Borneo monkeys lose a tenth of their habitat in a decade

(02/25/2014) Four species of langurs monkeys that are endemic to Borneo lost more than a tenth of their habitat in just ten years, finds a study published in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation.

Local communities key to saving the Critically Endangered Mexican black howler monkey

(02/14/2014) For conservation initiatives around the world, community involvement is often crucial. An additional challenge is how to conserve species once their habitats have become fragmented. A primatologist in Mexico is bringing these together in a celebration of a Critically Endangered primate species: the Mexican black howler monkey. In 2013 Juan Carlos Serio-Silva was part of a team that not only helped to secure the establishment of a protected area for the Mexican black howler monkey, but also engaged local communities in a week of festivities, dubbed the First International Black Howler Monkey Week.

(11/21/2013) Oil, gas, timber, gold: the Amazon rainforest is rich in resources, and their exploitation is booming. As resource extraction increases, so does the development of access roads and pipelines. These carve their way through previously intact forest, thereby interrupting the myriad pathways of the species that live there. For species that depend on the rainforest canopy, this can be particularly problematic.

Kids’ stories and new stoves protect the golden snub-nosed monkey in China

(11/12/2013) Puppet shows, posters and children’s activities that draw from local traditions are helping to save an endangered monkey in China. The activities, which encourage villagers—children and adults alike—to protect their forests and adopt fuel-efficient cooking stoves, have worked, according to a report published in Conservation Evidence. Local Chinese researchers, supported by the U.S.-based conservation organization Rare, designed the campaign to protect the monkeys.

Like humans, marmosets are polite communicators

(11/06/2013) Common marmoset monkeys have been described as having human-like conversations according to a team of researchers from the Princeton Neuroscience Institute.

Native to Brazil, marmosets are highly social animals, using simple vocalizations in a multitude of situations: during courtship, keeping groups together and defending themselves. They also, according to the study published in Current Biology, exchange cooperative conversations with anyone and everyone – not just with their mates.

(09/30/2013) Scientists have applied a species prioritization scheme to Brazil’s diverse mammals to deduce which species should become the focus of conservation efforts over the next few years in a new paper published in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science.