Among the huge diversity of insects there are some bewilderingly complex life cycles, but few can compete with the trigonalid wasps for the seemingly haphazard way they ensure their genes are passed to the next generation.

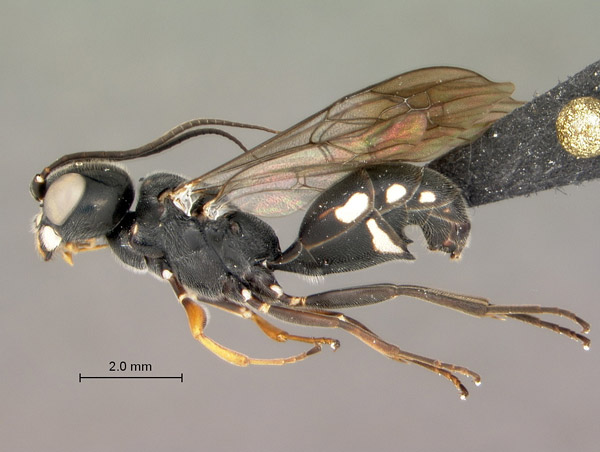

In most cases, a female parasitoid wasp deposits her eggs on or in the host, but this is far too pedestrian and safe for the trigonalids (image 1). These mavericks of the wasp world, which are also parasitoids, like to make things more difficult for themselves. So, the female deposits her eggs on plant leaves. If this were the end of the story these wasps would not have lasted very long. No, the egg-in-the-leaf-trick is merely a ruse. The female trigonalid uses her short ovipositor and the unique structure of her abdomen to punch out a small piece of tissue from near the margin of a leaf, replacing it with a flattened egg. She deposits a few eggs in one leaf before moving onto another leaf perhaps on a nearby plant. This goes on until she gets eaten by a predator or exhausts her eggs, which in some species of trigonalid can be as many as 10,000—a huge number for a parasitoid, which underlines just how haphazard this strategy is.

Trigonalys species (female). A species from the Central African Republic. These wasps have quite a distinctive appearance. Note the unusual shape of the abdomen that enables the female to press out a small piece of leaf tissue. Photo courtesy of Simon van Noort/www.waspweb.org.

The whole purpose of going through the laborious act of laying thousands of eggs in leaves is so her offspring can get swallowed by a caterpillar or the larva of a sawfly. If the very tough egg is lucky enough to get swallowed it hatches. This is thought to be triggered by the physical action of being chewed and/or salivary secretions.

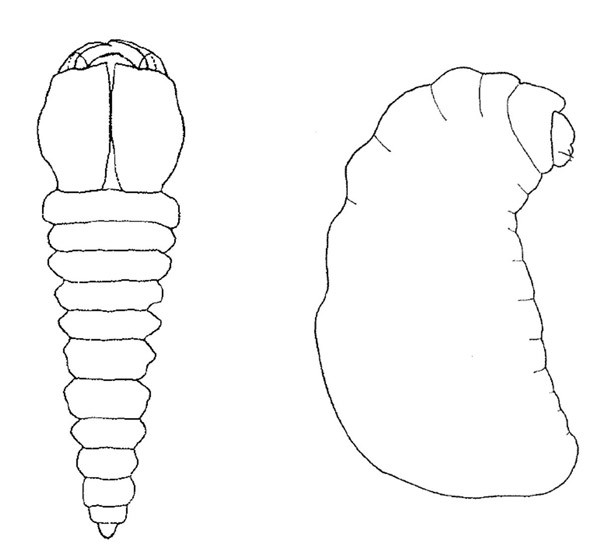

For most parasitoids, getting into a plump caterpillar would be mission completed and cause for celebration, but no such luck for the tiny trigonalid larva (Image 2). The tiny larva winds up in the caterpillar’s gut, but wastes no time in breaking out of there to gain entry to the caterpillar’s haemocoel, the insect body cavity that is bathed in haemolymph, analogous to our -blood. The trigonalid makes its way through this liquid searching for its real quarry—another parasitoid that is already living in the caterpillar. Lots of parasitoids, such as other wasps and flies, are dependent on the larvae of Lepidoptera and sawflies and it is these the trigonalid larva is after. If it’s lucky it will find its prey, attack them and eat them, but in many cases the trigonalid that has so far defied the odds to get swallowed by a caterpillar will find nothing suitable to predate once inside. Either that or the only parasitoid within the caterpillar will be too large for the trigonalid to tackle. In both cases the poor little trigonalid is doomed. However, some species of trigonalid are able to sit tight inside the caterpillar until it gets parasitized by an ichneumon or a tachinid fly.

But this isn’t the only bizarre life-cycle of the trigonalids. Another strategy used by some species also hinges heavily on coincidence, but the supporting cast is slightly different. These species still depend on a caterpillar or sawfly larva, but this time the caterpillar must be captured by a vespid or eumenid wasp, butchered and fed to one of the wasp’s grubs back at the nest. In the flesh of the dead caterpillar are the eggs of the trigonalid and once swallowed they hatch to feed on the unfortunate host larva.

In the world of wasps, trigonalids are something of an enigma. Only around 100 species are known, the adults don’t live very long and their precarious way of life means they are rather rare, so we don’t know a great deal about them. Their geographic distribution, appearance and lifestyle suggest they are very ancient and some entomologists have theorized they may be something of a missing link between the sawflies and bees, ants and wasps. Indeed, the oldest trigonalids are known from 100 million year old lumps of Cretaceous amber, which shows this way of life, precarious as it may be, has been going on for some time.

Like all insect larvae, immature trigonalids are unsightly to say the least. On the left we have a third instar larva of Bareogonalos jezoensis from Japan. This instar has huge mandibles for making short work of the prey. On the right is the final instar of the same species. The big mandibles have gone and instead we have a chubby beast with a tiny head. This species is a parasitoid of vespid wasps. Illustrations by: Seike Yamane, 1973.

Dr. Ross Piper is a zoologist and author and has recently presented on the BBC/Smithsonian TV production, Wild Burma: Nature’s Lost Kingdom, soon to be shown in the USA. You can read an interview with Ross Piper here: Animal Earth: exploring the hidden biodiversity of our planet.

|

Further reading:

- Yamane S. Descriptions of the second to final instar larvae of Bareogonalos jezoensis with some notes on its biology (Hymenoptera: Trigonalidae), Japanese Journal of Entomology (Kontyu) 1973;41:194-202.

- Weinsten P, Austin AD. The host relationships of trigonalyid wasps (Hymenoptera: Trigonalyidae), with a review of their biology and catalogue to world species. Journal of Natural History 1991;25:399-433.

Related articles

Sloths, moths and algae: a surprising partnership sheds light on a mystery

(03/22/2014) While it spends the majority of its time in the safety of tree canopies, the three-toed sloth regularly places itself in mortal danger by descending to the forest floor to defecate. For years, scientists have been trying to figure out what is driving this peculiar and risky behavior. Now, Jonathan Pauli from the University of Wisconsin-Madison believes his team of researchers has found an important clue to this mystery involving an unusual and beneficial relationship among sloths, moths and algae.

Scientist discovers a plethora of new praying mantises (pictures)

(03/19/2014) Despite their pacific name, praying mantises are ferocious top predators with powerful, grasping forelimbs; spiked legs; and mechanistic jaws. In fact, imagine a tiger that can rotate its head 180 degrees or a great white that blends into the waves and you’ll have a sense of why praying mantises have developed a reputation. Yet, many praying mantis species remain little known to scientists, according to a new paper in ZooKeys that identifies an astounding 19 new species from the tropical forests of Central and South America.

Scientists discover single gene that enables multiple morphs in a butterfly

(03/10/2014) Scientists have discovered the gene enabling multiple female morphs that give the Common Mormon butterfly its very tongue-in-cheek name. doublesex, the gene that controls gender in insects, is also a mimicry supergene that determines diverse wing patterns in this butterfly, according to a recent study published in Nature. The study also shows that the supergene is not a cluster of closely-linked genes as postulated for nearly half a century, but a single gene controlling all the variations exhibited by the butterfly’s wings.

Wonderful Creatures: meet the beetle-riding arachnid

(03/06/2014) Without wings, smaller terrestrial animals are really restricted when it comes to moving long distances to find new areas of habitat. However, lots of species get around this problem simply by clinging on to other, more mobile animals. The common, yet overlooked pseudoscorpions are among the most accomplished stowaways, one of which (Cordylochernes scorpiodes) has forged a fascinating relationship with the harlequin beetle, a large, strikingly colored insect.

Two new wasp species found hidden in museum collections

(02/24/2014) Scientists have identified two new wasp species, years after the specimens were first collected from the wild. The two new species, Abernessia prima and Abernessia capixaba, belong to the rare pompilid genus Abernessia, and are believed to be endemic to Brazil. They made the discovery while examining spider wasp collections from museums in Brazil and Denmark, and published their findings in the journal ZooKeys.

Alpine bumblebees capable of flying over Mt. Everest

(02/05/2014) The genus Bombus consists of over 250 species of large, nectar-loving bumblebees. Their bright coloration serves as a warning to predators that they are unwelcome prey and their bodies are covered in a fine coat of hair – known as pile – which gives them their characteristically fuzzy look. Bumblebees display a remarkably capable flight performance despite being encumbered with oversized bodies supported by relatively diminutive wings.

Migrating monarch butterflies hit shockingly low numbers

(01/31/2014) The monarch butterfly population overwintering in Mexico this year has hit its lowest numbers ever, according to WWF-Mexico. Monarch butterflies covered just 0.67 hectares in Mexico’s forest, a drop of 44 percent from 2012 already perilously low population. To put this in perspective the average monarch coverage from 1994-2014 was 6.39 or nearly ten times this year’s. For years conservationists feared that deforestation in Mexico would spell the end of the monarch migration, but now scientists say that agricultural and policy changes in the U.S. and Canada—including GMO crops and habitat loss—is strangling off one of the world’s great migrations.