Flying over the endless forest of the West Amazon, while searching for short-eared dogs. From so high up it was possible to see just how much forest there really is, and how much there is still to save. Photo courtesy of: Paul Rosolie.

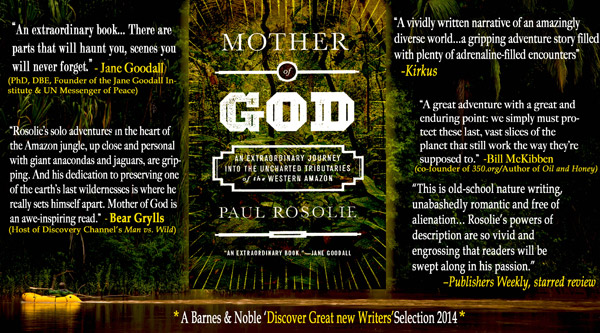

Not yet 30, Paul Rosolie has already lived a life that most would only dare dream of—or have nightmares over, depending on one’s constitution. With the Western Amazon as his panorama, Rosolie has faced off jaguars, wrestled anacondas, explored a floating forest, mentored with indigenous people, been stricken by tropical disease, traveled with poachers, and hand-reared a baby anteater. It’s no wonder that at the ripe age of 26, Rosolie has already written a memoir: Mother of God: An Extraordinary Journey into the Uncharted Tributaries of the Western Amazon. It’s an exuberant, brash, and thrilling adventure story, and already garnered praise from the Wall Street Journal, Publishers Weekly, while being selected in the Barnes and Noble 2014 Discover Great New Writers series. But what sets Rosolie’s book a part from other young adventurers, is that he’s not simply seeking thrills and regurgitating them to arm-chair enthusiasts. Instead Rosolie is spending every ounce of himself working to save one of the world’s last great wildernesses: the rainforest of Madre de Dios, or Mother of God. And he’s rewriting the rules of conservation in the process.

“I was always drawn to wilderness and wildlife; watching documentaries and reading books about rainforests were some of my favorite things to do,” Rosolie tells mongabay.com in a recent interview (printed in full below). “The Jungle World exhibit at the Bronx Zoo was a major influence on me. Interspersed throughout the exhibit were images and stories of biologists and explorers working in far flung countries with the most incredible animals. I figured if actual jungles were even half as amazing as that, then there could be nothing on earth more interesting.”

A female anaconda that JJ Durand and Paul Rosolie caught, just before releasing her back to the wild. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie. |

At 18, Rosolie first departed alone for the world’s greatest rainforest—the Amazon—to work at a local research station. Despite having grown up over three thousand miles away in concrete New Jersey, when he arrived in the Peruvian rainforests, Rosolie knew he’d come home.

“Within the first five minutes of being in the forest, I realized that all the hype I had absorbed as a kid about rainforests was nothing compared to the reality. I knew that the jungle was where I belonged,” he says.

Since then, Rosolie has had enough adventures to make Teddy Roosevelt, Ernest Shackleton, and Alfred Russel Wallace proud. But one just doesn’t go from city boy to Amazonian adventurer without some serious mentoring.

“My entire relationship with the Amazon, and with the wildlife there was made possible through the luck of meeting my friend and professor Juan Julio (or JJ) Durand. JJ and his family are part of the Ese-Eja indigenous community of Infierno on the Tambopata River, and from them I learned just about everything I know,” Rosolie explains, adding “We’d walk barefoot and track various species, from monkeys, tapirs, jaguar and peccary, to anaconda and giant anteaters. JJ taught me which trees could kill you, and which would just give you a debilitating rash. He also showed me which tree can help you survive a venomous snake bite. There are other trees that you can slash, and pour the sap directly into a diesel motor—and the truck will run…Most of what I know is from my local friends. The rest is the result of trial and error.”

‘Penis snake’ discovered in Brazil is actually a rare species of amphibian (August 01, 2012) A creature discovered by engineers building a dam in the Amazon is a type of caecilian, a limbless amphibian that resembles an earthworm or as some are noting, part of the male anatomy. |

It was with JJ, and the Durand family, that Rosolie started Tamandua Expeditions in a bid to preserve a patch of primeval forest along the Madre de Dios. Operating since 2007, Tamandua Expeditions offers a variety of trips to the Las Piedras Biodiversity Station, including everything from volunteer work to photography to yoga.

In just the few years that Rosolie has lived and worked on the Las Piedras River in Peru’d Madre de Dios region, he’s seen tremendous changes, and unprecedented destruction.

“Up until a few years ago the Las Piedras River was so long and isolated that much of its forest and wildlife and people were safe. But recently the Trans-Amazon highway was paved and completed, which caused a number of offshoot roads to be cut into what had previously been ancient, untouched forest…Now that the roads have been created we are seeing a massive influx of settlers from the Andes. Houses and farms are popping up each day and forest is being cleared with increasing speed. Loggers are using the roads to access stands of ironwood, cedar, and other old growth timber that is now exposed. It is very simply a free-for-all and poor people are flocking in to profit from the forest,” he says. But he warns of an even graver threat on the horizon: the so-called Purus Road.

“If created this road would be a devastating blow to one of the last truly authentic strongholds of wildlife, culture, and wilderness on our planet. And the thing is, this road is not essential for anyone, except a few people who stand to get rich quick if the road is built, because they’ll be able to export timber and other resources faster,” Rosole explains. “This road cannot be allowed to happen, but it is going to unless we work to stop it.”

This is a story playing out throughout the Amazon (and many other parts of the tropics). But Rosolie is far from hopeless. Inspired by the likes of Jane Goodall, Steve Irwin, and Alan Rabinowitz, Rosolie hopes his book—in concert with a number of up-coming, ambitious projects—will not only aid the Western Amazon, but also broaden the conservation movement, bringing in new acolytes and changing not only how we talk about conservation, but nature.

Packrafting in dangerous waters—in the swamps at night. Photo by: Mohsin Kazmi.

“There is not much consciousness of the natural world in our daily media-soaked lives,” he says. “It is like we are living in a vacuum of concrete and economics where we forget the simple truth of that old Carl Sagan line about how if you can’t breath the air and drink the water, nothing else you are interested in is going to be possible. That is the reality of living on a planet where we depend on the biosphere for life…What I would like to see is a reimagining of nature in literature and entertainment. I think that animals and ecological awareness needs to be something that becomes part of our culture. Right now it is not there…I would like to see more narratives tackling bigger issues—why not have main characters that are park rangers protecting gorillas? Or other professions that deal with defending wildlife/resources? I really think that if the idea of protecting, caring, fighting (you can make it action packed!) became more common in our cultural awareness, it would help change things.”

Rosolie’s new book very much follows this philosophy. He draws the reader in with real-life adventures, accessible language, and the power of the Amazon rainforest as the world’s greatest explosion of life. Yet at the same time, he delivers a passionate, hopeful message for a revolution that would view the natural world not as something to be exploited for endless and impossible economic growth, but as beyond wealth itself: as the greatest gift bestowed on humankind.

|

“The idea that the Amazon and other rainforests are vanishing has been beaten to death. I did not want to write a factual conservation book loaded down with dry statistics and graphs on deforestation. I have always been fascinated by the idea of ‘rebranding’ conservation. It’s not a sob-story lost cause that mainstream media portrays it to be,” Rosolie says. “It is the most exciting thing imaginable. Here you have the greatest proliferation of life in the known universe being funneled into a meat grinder that churns out money at the crossroads of global economics and the ecological health, and survival, of our entire planet. It is a struggle that will decide the fate of everything we know. Right now in Brazil there are indigenous people fighting the government’s plans to dam their home-river. In Africa there are elephants and rhinos being massacred by poachers and park rangers are fighting to protect them. Tigers are making their last stand across Asia where demand for palm oil is razing forests. It’s a brawl out here. The crisis of rainforests today is a lot like what my grandparents’ generation dealt with during the Second World War. If we lose this fight, it is all over.”

While the battle is currently ongoing, it’s by no means lost, according to Rosolie. He points to a flight he recently took above the heart of the Amazon: “Green. For hours. We were traveling at 140mph and all we saw were trees, interrupted by oxbow lakes and marshes, and the golden rivers that look like anacondas lying across the earth. It was incredible. And during the flight I kept thinking how we always hear about the destruction, and how time is running out. And it is true. But what we don’t hear, and don’t know, is that there is still so much left to save.”

Rosolie’s book, Mother of God: An Extraordinary Journey into the Uncharted Tributaries of the Western Amazon, hits stores tomorrow.

For past articles on Rosolie’s work: Secrets of the Amazon: giant anacondas and floating forests (March 2010), Hunting threatens the other Amazon: where harpy eagles are common and jaguars easy to spot (August 2010), and Jaguars, tapirs, oh my!: Amazon explorer films shocking wildlife bonanza in threatened forest (February 2013) .

INTERVIEW WITH PAUL ROSOLIE

CHAPTER ONE: THE BOOK

Official trailer for Mother of God: An Extraordinary Journey into the Uncharted Tributaries of the Western Amazon.

Mongabay: Without giving away any of your new book’s surprises (and there are many), why should people read Mother of God: An Extraordinary Journey into the Uncharted Tributaries of the Western Amazon?

Paul Rosolie: Mother of God is essentially classic adventure story in a modern setting: a young person’s search for meaning and adventure. But this journey leads deep beneath the canopy into the guts of the Amazon. There are lots of up-close encounters with some of the biggest and baddest of the jungle: jaguars, anacondas, giant anteaters. It is a book essentially about the incredible wilderness that is Amazonia, set in the context of a modern day Wild West where loggers, poachers, pimps, gold miners and drug runners prowl the massive backcountry that is a rapidly changing wilderness. It is at its core this book is a journey in search of understanding the humans/nature relationship.

Mongabay: You first traveled to the Amazon rainforest by yourself at the age of 18. What drew a kid from New Jersey to the world’s greatest rainforest?

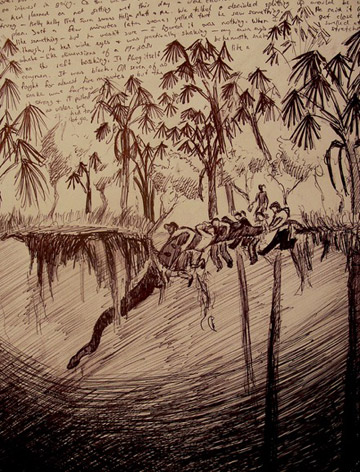

Secrets of the Floating Forest—the day that seven people tried to restrain a ~22ft anaconda. But the snake overpowered us and we were forced to let go, or be dragged under. Note, she did not retaliate (which she definitely could have). Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie. |

Paul Rosolie: I was always drawn to wilderness and wildlife; watching documentaries and reading books about rainforests were some of my favorite things to do. The Jungle World exhibit at the Bronx Zoo was a major influence on me. Interspersed throughout the exhibit were images and stories of biologists and explorers working in far flung countries with the most incredible animals. I figured if actual jungles were even half as amazing as that, then there could be nothing on earth more interesting. And so the idea of actually going to a rainforest became my dream—to see giant trees teeming with life of every variety, and unexplored regions. To me, rainforests became the most wondrous thing in all living reality.

But of course when you learn about rainforests, you inevitably learn that they are vanishing, and so I grew up with this ticking urgency that I needed to get out there and see these places, and these creatures, before they vanished.

I have always found classrooms dull, and by 10th grade I had had enough sitting around. So, with my parents’ encouragement I left high school and started college. Soon after turning eighteen, I started working as a lifeguard and saving money to follow my dream of visiting the biggest and baddest of all the rainforests: the Amazon. I found a small research team with open positions for students in the Peruvian Amazon and convinced them to take me. The region was called the Madre de Dios (or Mother of God). Within the first five minutes of being in the forest, I realized that all the hype I had absorbed as a kid about rainforests was nothing compared to the reality. I knew that the jungle was where I belonged.

Mongabay: How did you decide it was time to write a book?

Paul Rosolie: The idea that the Amazon and other rainforests are vanishing has been beaten to death. I did not want to write a factual conservation book loaded down with dry statistics and graphs on deforestation. I have always been fascinated by the idea of ‘rebranding’ conservation. It’s not a sob-story lost cause that mainstream media portrays it to be. It is the most exciting thing imaginable. Here you have the greatest proliferation of life in the known universe being funneled into a meat grinder that churns out money at the crossroads of global economics and the ecological health, and survival, of our entire planet. It is a struggle that will decide the fate of everything we know. Right now in Brazil there are indigenous people fighting the government’s plans to dam their home-river. In Africa there are elephants and rhinos being massacred by poachers and park rangers are fighting to protect them. Tigers are making their last stand across Asia where demand for palm oil is razing forests. It’s a brawl out here. The crisis of rainforests today is a lot like what my grandparents’ generation dealt with during the Second World War. If we lose this fight, it is all over.

Where the Andes meet the Amazon. The cloud forests of Manu, where moisture collects, and pours towards the lowlands. Photo by: Gowri Varanashi.

So I knew I wanted to tell the story of what is going on, but I wanted to tell it in a way that would reach more people and break the traditional conservation message mold. I wanted to convey the message of what we were losing without being overtly didactic – so I wanted to write something exciting and digestible and with a little more mainstream appeal. I have always been an avid reader of non-fiction adventure stories. My favorites were always the ones that dealt with wilderness sand wildlife where the author brought alive species or the essence of a place—and that had a good human story, where you also learned something. R.D. Lawrence’s The North Runner was one of my favorites growing up. And more recently I was completely amazed by John Vallient’s The Tiger. I looked to these greats while writing Mother of God.

Perhaps it is because I interact with the forest in a very intense way, or maybe because I am just lucky—or maybe the jungle gave me what I needed—but I’ve had a lot of unique encounters out there. From finding the floating forest, to raising a giant anteater, learning about anacondas, and spending time out in super-remote places. There came a point when I realized that the sum of these experiences painted a picture of the Amazon that I had not seen before in the literature of the Basin, and I for the first time felt there was something I could add to the genera. And so I began writing. That was back in 2009.

Mongabay: If they make a move of Mother of God, who stars as Paul Rosolie?

Paul Rosolie: With so many non-fiction books becoming movies, I keep getting asked this question. But I don’t think this story could ever work in movie form. There is just too much dangerous animal action with so many species that it would be impossible to film with real animals—which means they’d make the entire thing a computer animated travesty.

Also, I don’t know if there is anyone in Hollywood with thick enough eyebrows or a crooked enough nose to play me.

CHAPTER TWO: ADVENTURING

Traveling by packraft on the Piedras River, beneath towering walls of lush jungle. Photo by: Mohsin Kazmi.

Mongabay: You’ve had a number of close encounters in the Amazon. How do you stay as safe as possible when undertaking new expeditions into the forest or handling apex predators?

Paul Rosolie: First off, the jungle gets a bad wrap for being more dangerous than it really is. In reality, millions of people call the jungle home from infants to grandparents. Anywhere can be dangerous, wilderness or city, if you don’t know the rules. In fact cities are far more dangerous than any given section of peaceful Amazonia, but most people feel more familiar with concrete than trees. That being said I know that on many occasions I have tested the rules in the Amazon to the point of almost asking to get hurt (or worse).

The history of jungle exploration is abundant with accounts of men dying from infection. In 2007 an infection, spread rapidly by dozens of open wound mosquito bites (and subsequent scratching), almost killed Rosolie. He was stuck in the forest, while days passed and his fever rose, and not a boat passed by. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie. |

When I am out on a solo, alone in the jungle and days or weeks away from help I stay away from lakes at night (because of black caiman) and try and stay within a day’s hike of a river (because in the Amazon the sheer immensity of the forest is a very dangerous factor for a lost individual). I know that I should bring a SAT phone but somehow I feel like it compromises the isolation, and alters the experience. That might sound crazy, even moronic, but that is how it is.

As for handling apex predators, I try not to. But I’ve been working with, studying, and rescuing snakes since I was eight years old, and so am very comfortable with them. Just like how a person who has driven for twenty years knows the roads, and can anticipate other driver’s moves—I have an understanding of snakes. Despite working with bushmasters, cobras, kraits, coral snakes, and retics and anacondas I have never been bitten unless I was handling something harmless and wanted to show off. Fingers crossed it stays like that. But I’d say that knowing when to back off is the most important part of staying safe with wildlife. Sometimes you just don’t have control, and you gotta hit the brakes, before things go bad. It is really about respecting and understanding the animal.

Mongabay: Where did you learn your jungle survival skills?

Paul Rosolie: My entire relationship with the Amazon, and with the wildlife there was made possible through the luck of meeting my friend and professor Juan Julio (or JJ) Durand. JJ and his family are part of the Ese-Eja indigenous community of Infierno on the Tambopata River, and from them I learned just about everything I know.

Working with JJ over the years has made me a better wildlife spotter (and guide), but also led to knowledge of edible plants, medicines and other secrets that you can’t pick up by simply reading a book. We’d walk barefoot and track various species, from monkeys, tapirs, jaguar and peccary, to anaconda and giant anteaters. JJ taught me which trees could kill you, and which would just give you a debilitating rash. He also showed me which tree can help you survive a venomous snake bite. There are other trees that you can slash, and pour the sap directly into a diesel motor—and the truck will run. From JJ I know which nuts contain grubs to use as fishing bait, and how to slice the callous on the heal of my foot to make a durable piece of starter bait. So most of what I know is from my local friends. The rest is the result of trial and error.

Mongabay: I know you’ve been influenced by many adventurers, naturalists and conservationists. If you had to pick three to single out, though, who would they be and why?

Rosolie with the skull of a full grown black caiman, an endangered species and the Amazon’s largest predator. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie. |

Paul Rosolie: One of my biggest influences is without question Jane Goodall. When we were kids my mom would read stories about Dr. Goodall in Africa to me and my sister. She does so much work with children, and is a UN messenger of peace, and I think most people don’t realize that she is a complete badass. She traveled to Africa when she was only 23 at a time when girls didn’t do that kind of thing. There she began incredible work and made incredible discoveries that changed the way we view humans and nature. She is a champion of wildlife, and peace, and logic, and has been carrying the torch for decades. Her schedule even at 80 years old, requires traveling 300 days a year to inspire and teach people—she is completely incredible. Dr. Goodall’s generosity and care helped Mother of God to become a reality. If everyone followed her wisdom, the world would be a much better place.

Another great influence for me was Steve Irwin. Most people don’t realize that before he was The Crocodile Hunter he was in the backwoods of Australia rescuing 15 foot crocodiles with only his dog and a boat. He lived in the bush doing the most dangerous job imaginable for years simply because he loved and wanted to help crocs. Then after we all learned his name because of his show, he began Australia Zoo, and began doing serious salt-water crocodile research. He was a family man, incredibly skilled snake handler (and all wildlife really), and he inspired millions to care about wildlife. Including me. I can only imagine what he’d be doing if he were still alive today. If I could meet one person living or dead, it would be Steve. We’d have a lot of fun telling stories and catching snakes together.

Dr. Alan Rabinowitz of WCS and now Panthera is another major influence. When it comes to real world, on-the-ground conservation, Dr. Rabinowitz is in a class of effectiveness and innovation difficult to match. He has worked all over the world, in some truly difficult places, establishing sanctuaries for species like jaguars and tigers. He has the academic background and calm demeanor to approach world leaders and explain why protecting wildlife is essential to the well being of their country. He always says that he is the voice for wildlife that cannot speak for themselves. And that is a damn important job. We are not the only species on this planet, and other forms of life have a right to exist—and have their own reasons for existing. Rabinowitz is a wiseman, a badass, and an incredibly accomplished conservationist. He has my vote for President.

We call it ‘the Avatar tree’ a massive ficus on Las Piedras. An ancient treasure, one of thousands. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Mongabay: Your route into the world of conservation has been truly unique. For young people interested in conservation and rainforests in particular, what advice would you give?

Paul Rosolie: The most important thing is this: Get out there. The world needs you right now. There are limitless ways to become part of this fight, and everyone is going to have a different approach and path. Here are a few suggestions:

- For one thing, find some non-touristy eco-tourism operations, and visit them. Make sure to find ones that are actually doing conservation work. Get your friends to come too. Make contacts. It is important to remember that so many species and ecosystems being protected today are supported by ecotourism. So getting out there and experiencing these places yourself can actually help protect rainforest. Go have fun!

- Talk to your professors. Study abroad options in rainforest areas are a great way to get a taste of the field, and talk to people who can help you get a focused image of what you actually want to pursue, and how you can be useful.

- Don’t limit yourself. Conservation needs writers, photographers, engineers, scientists, filmmakers, publicists, lawyers, vets, and virtually limitless other talents and professions. If you are good at something, it can probably be used to protect rainforests. Musicians I know have provided free music at fundraising events for conservation organizations. Right now our efforts to protect the Las Piedras River are being supported by yoga groups; they travel to the jungle to practice yoga, and then spread the word and continue to help back home.

- Educate your friends and family. It drives me crazy how many people still are buying palm oil products, mahogany bed sets, and wildlife products. Most people do it because they don’t realize the cost of their actions. If we cut out the demand for these products, the extraction will stop.

CHAPTER THREE: LAS PIEDRAS AND THE FUTURE OF THE AMAZON

Logging on the road from the Trans-Amazon highway to Las Piedras. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Mongabay: What are the major ongoing threats to the Las Piedras River where you work?

Paul Rosolie: Up until a few years ago the Las Piedras River was so long and isolated that much of its forest and wildlife and people were safe. But recently the Trans-Amazon highway was paved and completed, which caused a number of offshoot roads to be cut into what had previously been ancient, untouched forest. And one of these now leads from the mega-highway directly onto the Las Piedras River—turning what was once deep jungle into a new center for resource extraction. Now that the roads have been created we are seeing a massive influx of settlers from the Andes. Houses and farms are popping up each day and forest is being cleared with increasing speed. Loggers are using the roads to access stands of ironwood, cedar, and other old growth timber that is now exposed. It is very simply a free-for-all and poor people are flocking in to profit from the forest.

People don’t realize how delicate wildlife is. I have personally witnessed a single hunter cause the local extinction of an entire species. So for the wildlife and cultures on the Las Piedras the situation is urgent.

But the Las Piedras is not only the heart of the Madre de Dios, and a sanctuary for wildlife—but it is one of the last strongholds for the few remaining isolated indigenous tribes that still maintain a nomadic way of life. So there is much to lose here. But the most devastating threat approaching is yet another road, that is proposed to cut into one of the most pristine places on earth. To quote from the Upper Amazon Conservancy, “The highway would cross the Alto Purús National Park and the Madre de Dios Territorial Reserve for Indigenous People in Voluntary Isolation, home to some of the last isolated indigenous tribes left anywhere in the world.”

If created this road would be a devastating blow to one of the last truly authentic strongholds of wildlife, culture, and wilderness on our planet. And the thing is, this road is not essential for anyone, except a few people who stand to get rich quick if the road is built, because they’ll be able to export timber and other resources faster. This road cannot be allowed to happen, but it is going to unless we work to stop it.

Mongabay: Will you give us an update on your campaign in the Amazon to preserve the lower Las Piedras River?

The plummeting waterfalls at the edge of the Andes create the start of the greatest river system on earth. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie. |

Paul Rosolie: These efforts are still in their infancy. We are trying to raise awareness about the river and its positional significance between the other major protected areas in the Madre de Dios. We are doing this through film, writing (this book!), and ecotourism. It is a complex task to protect this river. Most of the land is divided up into concessions and so anything you want to do has to include dozens of stakeholders. Thankfully many of the landowners on Las Piedras are wholly in support of protecting the river and stemming the unregulated influx of settlers and extractors that are currently flooding in.

But this river is too important to lose. From the rich forests, to healthy wildlife, to the fact that it is a buffer zone and homeland for uncontacted tribes, it simply needs more attention. Currently there is a lot of great work beginning on Las Piedras. I am optimistic for the future, although it will not easy. I cannot emphasize enough that this is a crucial time for the river. In the back of Mother of God I have invited readers to take part, and visit www.tamanduajungle.com and click on Junglekeepers to find out how you can get involved. We are currently doing a ton of exciting work including making a feature length documentary, beginning new studies, and promoting this book to let people know about our journey – join up and find out how you can help!

Mongabay: The news that the Amazon rainforest is in peril has been reported for decades and may seem hopeless to many. How do we invigorate a new movement to step up and preserve what remains?

Paul Rosolie: I don’t think it is hopeless, but it also is not pretty. One of the main problems in my opinion is that this fight has a very weak mainstream identity. Where do we hear about the value of ecosystems, or about what wildlife contributes to our lives? We don’t, really. Each person assumes that wildlife and nature are ‘somewhere else’, but not around where they live. The problem is we are all living in it.

Right now when you go on CNN.com and look to the subjects bar, you’ll see things like Business, Politics, Justice, Entertainment, Tech, Health, Travel, and Money. The same goes for the BBC and other news sources. The point is, there is not much consciousness of the natural world in our daily media-soaked lives. It is like we are living in a vacuum of concrete and economics where we forget the simple truth of that old Carl Sagan line about how if you can’t breath the air and drink the water, nothing else you are interested in is going to be possible. That is the reality of living on a planet where we depend on the biosphere for life. Like it or not.

The way I see it the people who really care are already doing something about it, in one way or another. But what I would like to see is a reimagining of nature in literature and entertainment. I think that animals and ecological awareness needs to be something that becomes part of our culture. Right now it is not there. I was very happy to see a natural feeling conservation message as part of the move The Descendants (2011). But other than that I struggle to think of examples. I would like to see more narratives tackling bigger issues—why not have main characters that are park rangers protecting gorillas? Or other professions that deal with defending wildlife/resources? I really think that if the idea of protecting, caring, fighting (you can make it action packed!) became more common in our cultural awareness, it would help change things. I think we need to realize that the people that are keeping our world functioning, and beautiful, and exciting (i.e. keeping our biodiversity intact and alive) are the heroes, and that needs to be reflected in our culture to inspire more people.

Mongabay: What can people who live far away from the Amazon do to help protect this ecosystem?

Traveling with poachers, Rosolie witnessed a slaughter of wildlife. Monkeys, black caiman, macaws, and many, many peccary. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: This is the most important question! Most people reading this book or this interview don’t live near a rainforest. But there are actually many ways to help from home, wherever you live.

First off is being a responsible consumer. There are certain things that are devastating rainforests all over the world: palm oil, soy, beef, mahogany, wildlife products. Many times people don’t realize that the things they are buying are directly funding the destruction of wildlife and rainforests on the other side of the globe. So getting educated and helping friends and family to do the same is massive. It doesn’t sound very romantic, but it is damn effective.

Another thing is that many people make the mistake of thinking of conservation as made up of only field biologists. In reality it takes a tremendous diversity of disciplines and professions to make projects on the ground successful. There are conservation groups all over the world that could probably benefit from your help. Just working with ecotourism legal, travel, tech, publicity, video/photo, journalists, and so much more. Chances are you have skills that people desperately need. That wildlife desperately needs. Get involved.

This is one of my focuses currently: finding out how to better connect people across the globe on projects. There are so many people in the US and Canada for instance, that would love to take a more active role in conservation of resources, wilderness, species, and cultures in rainforests around the world, but currently there are limited ways to do this. In the next month we are going to be unveiling www.Junglekeepers.org—a completely new project that we are hoping is going to revolutionize who conservation works. Connecting everyone, and maximizing results in the real world!

And the final thing that people can do is buy a copy of this book! Get a copy for a friend. A big part of the proceeds from the book are going straight towards protecting the west Amazon, and Las Piedras.

Mongabay: Can you give us some hints of what you’re working on next?

Paul Rosolie: Priority number one right now is protecting Las Piedras, raising funds and support for that is a full time job! But there are some amazing things on the horizon with anaconda work—so big that I cannot divulge anything now. But I will say that we might be making history. There also may be a mega-expedition in store across the entire Andes/Amazon range as well, which I am very excited for.

Mongabay: What keeps you hopeful?

A nap with orphan giant anteater Lulu. Photo courtesy of Paul Rosolie.

Paul Rosolie: There is a lot! People all over the globe are starting to care, to really actually care in a way that makes them want to take action. Even people who think in economic terms (countries/corporations) are beginning to realize that it’s better to have working oceans, intact ecosystems and forests etc. than to not have these systems. People are starting to realize that we really need nature. Even at my local grocery store, people now bring bags instead of using plastic. People are starting to care more about where their food comes from as well. It’s a small thing, but it is indicative of a larger shift in awareness and responsibility.

But if you want to really know what makes me hopeful, I must tell a story. It happened on the fringe of the Madre de Dios, right near Manu National Park. I was with Renata Leite Pitman, the world’s leading expert on short-eared dogs (Atelocynus microtis)—one of the most elusive mammals on earth. We were searching for an individual short-eared dog that Renata had collared a few years back. But in order to find the free-ranging wild dog, we had to enter uncontacted Indian territory. So before we could go up river by boat, we went scouting by air. We took a Cessna over the jungle, with Renata’s telemetry equipment duct-taped to the wings.

The flight only lasted about two hours but I’ll never forget what we saw. We were just at the eastern limit of the Andes, and the western limit of the Amazon, where the mountains drop down into the basin in sheets of green foliage and waterfalls. For the first ten minutes we could see the mountains, but soon we were deep enough into the Basin that all you could see was endless green. It was a clear day and we were low over the jungle—forest stretching for as far as the eye could see in every direction. Green. For hours. We were traveling at 140mph and all we saw was trees, interrupted by oxbow lakes and marshes, and the golden rivers that look like anacondas lying across the earth. It was incredible. And during the flight I kept thinking how we always hear about the destruction, and how time is running out. And it is true. But what we don’t hear, and don’t know, is that there is still so much left to save. Right now as you read these word, it is out there. So much sprawling jungle out there that it is difficult to comprehend. You can still fly for hours and still see nothing but Amazon. Let’s, all of us, keep it that way.

Mother of God: An Extraordinary Journey into the Uncharted Tributaries of the Western Amazon. Click to enlarge.

Baby anaconda. Photo by: Gowri Varanashi.

A Castillia metalmark, a few others from the incredible cast of over 1400 species of butterflies that make the west Amazon the world record holder for butterfly diversity. It is common to see dozens of species on the riversides together, flying in rainbow vortexes that can envelope you in color. Photos by: Paul Rosolie.

Related articles

Controversial Amazon dams may have exacerbated biblical flooding

(03/16/2014) Environmentalists and scientists raised howls of protest when the Santo Antônio and Jirau Dams were proposed for the Western Amazon in Brazil, claiming among other issues that the dams would raise water levels on the Madeira River, potentially leading to catastrophic flooding. It turns out they may have been right: last week a federal Brazilian court ordered a new environmental impact study on the dams given suspicion that they have worsened recent flooding in Brazil and across the border in Bolivia.

Amazon trees super-diverse in chemicals

(03/03/2014) In the Western Amazon—arguably the world’s most biodiverse region—scientists have found that not only is the forest super-rich in species, but also in chemicals. Climbing into the canopy of thousands of trees across 19 different forests in the region—from the lowland Amazon to high Andean cloud forests—the researchers sampled chemical signatures from canopy leaves and were surprised by the levels of diversity uncovered.

Sharp jump in deforestation when Amazon parks lose protected status

(03/01/2014) Areas that have had their protected status removed or reduced have experienced a sharp increase in forest loss thereafter, finds a new study published by Imazon, a Brazilian NGO.

Is Brazil’s epic drought a taste of the future?

(02/25/2014) With more than 140 cities implementing water rationing, analysts warning of collapsing soy and coffee exports, and reservoirs and rivers running precipitously low, talk about the World Cup in some parts of Brazil has been sidelined by concerns about an epic drought affecting the country’s agricultural heartland.

New $20,000 reporting grant explores benefits of Amazonian protected areas

(02/21/2014) With six Special Reporting Initiatives (SRI) already under way, Mongabay.org is excited to announce a call for applications for its latest journalism grant topic: Amazonian protected areas: benefits for people. The Amazon’s system of protected areas has grown exponentially in the past 25 years. In many South American nations, the mission of protected areas has expanded from biodiversity conservation to improving human welfare. However, given the multiple purposes and diverse management of many protected areas, it is often difficult to measure their effect on human populations.

The making of Amazon Gold: once more unto the breach

(02/19/2014) When Sarah duPont first visited the Peruvian Amazon rainforest in the summer of 1999, it was a different place than it is today. Oceans of green, tranquil forest, met the eye at every turn. At dawn, her brain struggled to comprehend the onslaught of morning calls and duets of the nearly 600 species of birds resounding under the canopy. Today, the director of the new award-winning film, Amazon Gold, reports that “roads have been built and people have arrived. It has become a new wild west, a place without law. People driven by poverty and the desire for a better life have come, exploiting the sacred ground.”

(02/13/2014) These are sights that have rarely been seen by human eyes: a stealthy jaguar, a bustling giant armadillo, and, most amazingly, a sloth slurping up clay from the ground. A new compilation of camera trap videos from Yasuni National Park in the Ecuadorean Amazon shows a staggering array of species, many cryptic and rare.

Helping the Amazon’s ‘Jaguar People’ protect their culture and traditional wisdom

(02/11/2014) Tribes in the Amazon are increasingly exposed to the outside world by choice or circumstance. The fallout of outside contact has rarely been anything less than catastrophic, resulting in untold extinction of hundreds of tribes over the centuries. For ones that survived the devastation of introduced disease and conquest, the process of acculturation transformed once proud cultures into fragmented remnants, their self-sufficiency and social cohesion stripped away, left to struggle in a new world marked by poverty and external dependence

Drought, fire reducing ability of Amazon rainforest to store carbon

(02/06/2014) New research published in Nature adds further evidence to the argument that drought and fire are reducing the Amazon’s ability to store carbon, raising concerns that Earth’s largest rainforest could tip from a carbon sink to a carbon source.

Amazon rainforest does not ‘green up’ during the dry season

(02/06/2014) Analysis of satellite imagery has cleared up a controversy over whether the Amazon rainforest ‘greens up’ during the dry season.

Brazilian soy industry extends deforestation moratorium

(02/01/2014) Soy traders and producers in the Brazilian Amazon agreed to extend a moratorium on soybeans produced in recently deforested areas for another year, reports Greenpeace.

287 amphibian and reptile species in Peruvian park sets world record (photos)

(01/28/2014) It’s official: Manu National Park in Peru has the highest diversity of reptiles and amphibians in the world. Surveys of the park, which extends from high Andean cloud forests down into the tropical rainforest of the Western Amazon, and its buffer zone turned up 155 amphibian and 132 reptile species, 16 more than the 271 species documented in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park in 2010.

New dolphin discovered in the Amazon surprises scientists

(01/23/2014) Researchers have discovered a new species of river dolphin from the Amazon. Writing in the journal Plos One, scientists led by Tomas Hrbek of Brazil’s Federal University of Amazonas formally describe Inia araguaiaensis, a freshwater dolphin that inhabits the Araguaia River Basin. It is the first true river dolphin discovered since 1918.

Red toad discovered in the upper reaches of the Amazon

(01/19/2014) Scientists have described a previously unknown species of toad in the Peruvian Andes.

High-living frogs hurt by remote oil roads in the Amazon

(01/14/2014) Often touted as low-impact, remote oil roads in the Amazon are, in fact, having a large impact on frogs living in flowers in the upper canopy, according to a new paper published in PLOS ONE. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park, massive bromeliads grow on tall tropical trees high in the canopy and may contain up to four liters of standing water. Lounging inside this micro-pools, researchers find a wide diversity of life, including various species of frogs. However, despite these frogs living as high as 50 meters above the forest floor, a new study finds that proximity to oil roads actually decreases the populations of high-living frogs.

Brazil begins evicting illegal settlers from hugely-imperiled indigenous reserve

(01/06/2014) Months after closing sawmills on the fringes of an indigenous reserve for the hugely-imperiled Awá people, the Brazil government has now moved into the reserve itself to evict illegal settlers in the eastern Amazon. According to the NGO Survival International, Brazil has sent in the military and other government agents to deal with massive illegal settlements on Awá land for logging or cattle.

Assassination 25 years ago catalyzed movement to protect the Amazon

(12/22/2013) Twenty-five years ago today, Chico Mendes, an Amazon rubber tapper, was shot and killed in front of his family at his home in Acre, Brazil at the age of 44.