In November this year, the world was greeted by the dismaying news that deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon jumped 28% in the past year. The year 2013 also holds the dubious distinction of being the first time since humans appeared on the planet, that carbon concentrations in the atmosphere rose to 400 parts per million. A map by Google revealed that Russia, Brazil, the United States, Canada and Indonesia all displayed over 10 million hectares of gross forest loss from 2000-2012, with the highest deforestation rate occurring in Malaysia. Despite some critiques of the technology, the map predicts a future in which technology will increasingly reveal the true scope of habitat destruction wrought on the planet by the human race. In these tumultuous times, some scientists have made a strong case for the preservation not only of pristine forests, but also areas subject to high human-modification, particularly in the tropics.

Pedro H. S. Brancalion, of the Department of Forestry in the University of São Paulo in Brazil, along with three colleagues, have outlined a conservation strategy for the protection of human-disturbed lands in mongabay.com’s open access journal Tropical Conservation Science.

There were only 562 individual golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) alive when censused in 1992, spread over 10.5 square kilometers of fragmented rainforest. An incredible effort at reintroduction has raised those numbers to 1,000 today, but predation and habitat destruction still threaten those numbers today. They are listed as Endangered on the IUCN species red list. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler.

In their paper, the authors define biodiversity-unfriendly landscapes (also known as human-disturbed landscapes) as “dominated by agriculture and/or urbanization and present a reduced native forest cover distributed in small, disconnected remnants, which are commonly exposed to human disturbances such as hunting, logging, fires, soil erosion, biological invasions, etc.”

The authors posit that such chronically disturbed landscapes “are still able to provide shelter for biodiversity and deliver ecosystem services to humans, but there is no guarantee that these benefits will continue in the long term if not adequately managed.”

They examine in some detail how forest restoration in such biodiversity-unfriendly landscapes can and does enhance biodiversity persistence and the delivery of ecosystem services. Ecological restoration can reconnect isolated populations of plants and animals by providing corridors of forest cover. Arrested succession of forests is common, caused by “severe edge effects, altered microclimatic conditions, and chronic small-scale disturbances such as intense fragmentation, recurrent fires, logging, and biological invasions.” Thus, ecological restoration can also improve the quality of the ecosystem by focusing on establishing natural successional trajectories in disturbed fragments.

When such adaptive management is absent, however, the scientists warn that present environmental conditions “favor canopy colonization by hyperabundant climbers, community dominance by a small set of pioneer species, and the recruitment of alien species, which may keep forest remnants in an alternative steady state.”

The highly fragmented Brazilian Atlantic Forest, famous for being home to some of the most endangered and endearing primates – the lion tamarins, are an excellent case in point. The authors discuss how restoration projects provide three million direct and indirect local jobs and 18 billion USD in global investments each year in the Atlantic Forest. They also stimulate the economy of the surrounding local populations by providing spaces where timber and non-timber forest products can be grown, providing valuable ecosystems services, and job and income generation.

Branculio warns that due to the spatial requirements of biodiversity, such potential can only be realized when ecological restoration is carried out on extremely large scales. The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity recognizes this in its target for restoring 150 million hectares by 202 (The Aichi Target 15).

“Conservation biologists have historically looked with suspicion at the potential of ecological restoration to reverse ecosystem degradation and mitigate species loss, while restoration ecologists may have overestimated the possible outcome of their projects in the highly-fragmented landscapes that occur throughout the tropics,” the authors conclude. With adaptive management strategies such as those being practiced in the Atlantic Forest today, the authors suggest that a balance between these two views can certainly be achieved to the benefit of local communities living around these fragments, as well as the wildlife that reside within them.

Citations:

- Brancalion, P. H. S., Melo, F. P. L., Tabarelli, M. and Rodrigues, R. R. 2013. Biodiversity persistence in highly human-modified tropical landscapes depends on ecological restoration. Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (6):705-710.

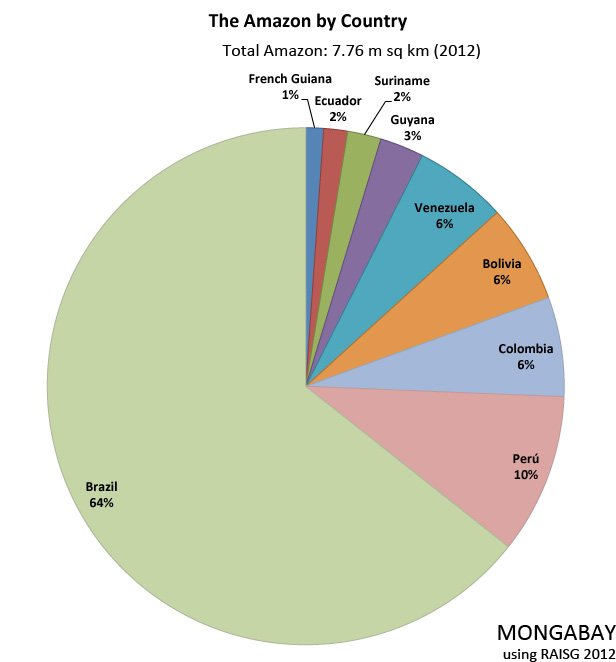

Nearly two-thirds of the Amazon rainforest is present within Brazil.

Related articles

Reforestation can’t offset massive fossil fuels emissions

(12/13/2013) With the Australian, Japanese, and Canadian governments making an about-face on carbon-emissions reduction targets during the Warsaw climate summit, some experts are warning that the global need for solutions offsetting CO2 emissions is passing a “red line.” Land-based mitigation practices comprise one of the solutions on the table as a result of both the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol; however, a paper published in Nature Climate Change by an international team led by Brendan Mackey, has raised the looming question of whether or not land-based practices can actually improve CO2 levels as much as hoped.

Climate change could kill off Andean cloud forests, home to thousands of species found nowhere else

(09/18/2013) One of the richest ecosystems on the planet may not survive a hotter climate without human help, according to a sobering new paper in the open source journal PLoS ONE. Although little-studied compared to lowland rainforests, the cloud forests of the Andes are known to harbor explosions of life, including thousands of species found nowhere else. Many of these species—from airy ferns to beautiful orchids to tiny frogs—thrive in small ranges that are temperature-dependent. But what happens when the climate heats up?

Market for REDD+ carbon credits declines 8% in 2012

(05/30/2013) The market for carbon credits generated from projects that reduce deforestation and forest degradation — a climate change mitigation approach known as REDD+ — dipped eight percent in 2012 according to an annual assessment of the global voluntary carbon market.

Disney buys $3.5M in REDD credits from rainforest conservation project in Peru

(03/20/2013) The Walt Disney Company has purchased $3.5 million dollars’ worth of carbon credits generated via rainforest conservation in Peru, reports Point Carbon.

Recovery of Atlantic Forest depends on land-use histories

(12/10/2012) The intensity of land-use influences the speed of regeneration in tropical rainforests, says new research. Tropical rainforests are a priority for biodiversity conservation; they are hotspots of endemism but also some of the most threatened global habitats. The Atlantic Forest stands out among tropical rainforests, hosting an estimated 8,000 species of endemic plants and more than 650 endemic vertebrates. However, only around 11 percent of these forests now remain.