Across New Guinea, deforestation is occurring at increasing levels. Whether it be industrial logging, monoculture plantations, hunters felling trees in pursuit of arboreal wildlife, or other forms of forest conversion, deforestation is depleting not only forest carbon stocks and understory environments, but habitats for species who call tree cavities “home.” A new study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal, Tropical Conservation Science, evaluated whether a variety of man-made nest boxes could function as suitable substitutes for tree cavities.

Worldwide, New Guinea contains the third largest rainforest. Many of the flora, fauna, and fungi in New Guinea are unique to its borders. According to the study, “over 70 percent of its forest birds and mammals are not found outside New Guinea and its associated offshore islands.”

Tree cavities, or hollows, serve a crucial role for species relying on them for habitats. Not only do cavities provide protection from predators but also necessary microclimates where the cavity itself is atmospherically unique compared to the surrounding area, much like dens. If cavities are not amply available, species populations depending on tree cavities are likely adversely affected.

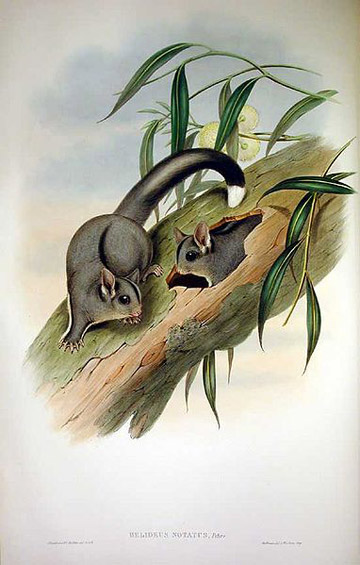

An illustration of sugar gliders (found in both Australia and New Guinea) using a nest cavity. By: John Gould. |

Since cavities are a critical resource and human activities are affecting their numbers in New Guinea, the successful use of nest boxes as a management strategy, elsewhere, lends itself as plausible. The scientists, lead by Diatpain Waraki conducted a unique study, assessing naturally occurring cavity availability in both primary and secondary forests. Once the amount and location of the cavities were determined, artificial nest boxes were placed in three different elevations. After eight months or two years the boxes were monitored to see if animals were using them as habitats.

Identifying the amount of naturally occurring cavities as well as their location in primary and secondary forests presents a consistent methodological challenge. For Waraki and his team, it was no different: 75% of cavities were missed until the trees were laid on the ground.

Methods of identification required, two separate plots to be walked, each measuring one-hectare. While walking plots, trees were tapped to see if they sounded hollow. Binoculars were used to assist with identification of possible cavities while also looking for snapped branches, or parts of the tree that were dead, dying, or partially rotten. Tapped and inspected trees in the two, one-hectare plots were then felled to determine if the above methods were an accurate means of identifying tree cavities in standing trees. Once on the ground, trees were checked for holes that contained nests or any remnants (e.g., feathers, claw or teeth marks) indicating they had been inhabited. Finally, trees were sectioned and removed so all parts of the tree could be examined. Of the thirty-six trees inspected for cavities in the primary forest, only nine were identified correctly as having cavities. Seventeen trees, once on the ground, were found to contain cavities. Three of the trees found to have cavities had more than one. From the secondary forest, ten were identified as potentially having cavities, yet none did once they were inspected when on the ground. Primary forests are generally considered important for cavity-dependent species as cavities are more common in older trees.

Five different nest boxes were built following prescribed designs for boxes used in Australia since the fauna in New Guinea and Australia are related; however boxes were modified due to New Guinea’s distinct wetter and tropical climate. Boxes were tested in Wasu and Mt. Gahavasuka Provincial Park. A total of 190 nest boxes were placed: 160 at Wasu and 30 at Mt. Gahavasuka.

Nest box in Papua New Guinea. Photo courtesy of Warakai et al. |

Various mammals, birds, reptiles, bees, and invertebrates were found to inhabit or had inhabited the artificial habitats in the study. The largest nest boxes were used most. Depending on the site, examples of specific species found were: sugar gliders (Wasu and Gahav), silky cuscus (Gahav), northern common cuscus (Wasu), Diehl’s ground snake (Wasu), and geckos (Wasu).

The Gahavasuka site allowed the team to study species use of nest boxes across a two-year time period whereas Wasu was studied for eight months. The scientists found occupying mammals or evidence of past occupation in 60% of the boxes at Gahavasuka. At Wasu, only 15% of boxes were occupied or showing occupancy after eight months. As a result the scientists concluded that “occupancy increases with time and was still increasing after two years” at Gahavasuka.

Implications of this study highlight that naturally occurring cavities are a valuable resource for many vertebrate species. The presence of cavities is rare and when found they are commonly located in large trees that have a high market value. Logging and hunting wildlife living in tree cavities will destroy potential breeding sites and will affect species having a safe habitat away from predators.

The scientists suggested educating hunters and loggers on best practices as a counter-strategy; however, the challenge of identifying the presence of cavities remained. While nest boxes may effectively mitigate some of the damage, the scientists warn that the cost of maintenance and doubts over the long-term efficacy could still undercut conservation efforts despite a range of vertebrates (gecko to large marsupial) inhabiting nest boxes.

Citations:

- Warakai, D., Okena, D. S., Igag, P., Opiang, M. and Mack, A. L. 2013. Tree cavity-using wildlife and the potential of artificial nest boxes for wildlife management in New Guinea. Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (6):711-733.

Related articles

Palm oil licenses provide cover for logging in New Guinea

(08/14/2013) Developers are seeking palm oil concessions to as a means to circumvent restrictions on industrial logging in Papua New Guinea, finds a new study published in the journal Conservation Letters. The research, led by Paul Nelson and Jennifer Gabriel of James Cook University, is based on analysis of 36 proposed oil palm concessions covering nearly 950,000 hectares in PNG. The study assessed the likelihood of the concessions coming to fruition. It found that only five concessions, covering 181,700 ha, are likely to be developed.

(06/05/2013) The tenkile, or the Scott’s tree kangaroo (Dendrolagus scottae) could be a cross between a koala bear and a puppy. With it’s fuzzy dark fur, long tail and snout, and tiny ears, it’s difficult to imagine a more adorable animal. It’s also difficult to imagine that the tenkile is one of the most endangered species on Earth: only an estimated 300 remain. According to the Tenkile Conservation Alliance (TCA), the tenkile’s trouble stems from a sharp increase of human settlements in the Torricelli mountain range. Once relatively isolated, the tenkile now struggles to avoid hunters and towns while still having sufficient range to live in.

Scientists describe over 100 new beetles from New Guinea

(06/03/2013) In a single paper, a team of researchers have succinctly described 101 new species of weevils from New Guinea, more than doubling the known species in the beetle genus, Trigonopterus. Since describing new species is hugely laborious and time-intensive, the researchers turned to a new method of species description known as ‘turbo-taxonomy,’ which employs a mix of DNA-sequencing and taxonomic expertise to describe species more rapidly.

Could the Tasmanian tiger be hiding out in New Guinea?

(05/20/2013) Many people still believe the Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus) survives in the wilds of Tasmania, even though the species was declared extinct over eighty years ago. Sightings and reports of the elusive carnivorous marsupial, which was the top predator on the island, pop-up almost as frequently as those of Bigfoot in North America, but to date no definitive evidence has emerged of its survival. Yet, a noted cryptozoologist (one who searches for hidden animals), Dr. Karl Shuker, wrote recently that tiger hunters should perhaps turn their attention to a different island: New Guinea.

Scientists: bizarre mammal could still roam Australia

(01/03/2013) The continent of Australia is home to a wide variety of wonderfully weird mammals—kangaroos, wombats, and koalas among many others. But the re-discovery of a specimen over a hundred years old raises new hopes that Australia could harbor another wonderful mammal. Examining museum specimens collected in western Australia in 1901, contemporary mammalogist Kristofer Helgen discovered a western long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus bruijnii). The surprise: long-beaked echidnas were supposed to have gone extinct in Australia thousands of years ago.