Meat. Photo by: National Institute of Health/Public Domain.

A new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has measured the “trophic level” of human beings for the first time. Falling between 1 and 5.5, trophic levels refer to where species fit on the food chain. Apex predators like tigers and sharks are given a 5.5 on trophic scale since they survive almost entirely on consuming meat, while plants and phytoplankton, which make their own food, are at the bottom of the scale. Humans, according to the new paper, currently fall in the middle: 2.21. However, rising meat-eating in countries like China, India, and Brazil is pushing our trophic level higher with massive environmental impacts.

“In the global food web, we discover that humans are similar to anchovy or pigs and cannot be considered apex predators,” the researchers write in the new paper.

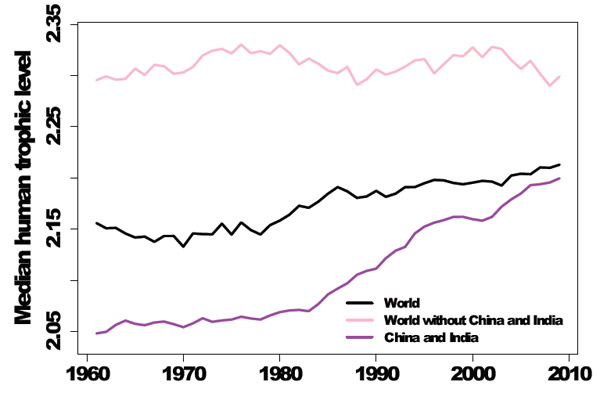

Using data from the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) going back nearly 50 years, the scientists find that the human trophic level has risen from around 2.15 in the 1970s to 2.21 today. Trophic levels are on the rise in many developing countries as economies have expanded and millions have come out of poverty. However, the change has come with drastic environmental impacts: meat-eating is less-efficient than a plant based diet and, as such, generally requires far more land, water, and energy to produce the same amount of calories.

The new study also evaluated human trophic levels (HTL) country-by-country, and found, not surprisingly, a wide variation in trophic levels across the world.

“In 2009, Burundi had an [human trophic level (HTL)] of 2.04, representing a diet that is almost completely (96.7 percent) plant based. In contrast, Iceland had an HTL of 2.57 for the same year, representing a diet composed of 50 percent meat and fish and 50 percent plants,” the researchers write.

Median trophic levels of various countries 2005-2009. Map courtesy of: Bonhommeau et al.

The scientists also found that a country’s trophic levels generally corresponded to World Bank development indicators.

“[Human trophic level] is positively related to, for example, gross domestic product, life expectancy, CO2 emissions, and urbanization rate until a point after which the relationships plateau and then turn negative,” write the researchers.

The scientists clump the world’s countries into five different categories based on trophic level trends over the last four decades. Group one includes countries with low levels (i.e. mostly plant-eating) that remain stable, such as most of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Groups two and three are those that had lower trophic levels to start with, but are rapidly rising. These include India, China, Brazil, and southern Europe. Meanwhile, the U.S., Canada, Australia, Eastern Europe, and New Zealand make up the fourth group where trophic levels were high but began to decline in the 1990s. Finally, group five are those countries with the highest trophic levels—Iceland, Scandinavia, Mongolia, and Mauritania—but which are now declining as well.

Still, rising meat eating in rapidly-developing countries has outweighed declining meat consumption in parts of the wealthy world. Moreover, population growth has keep meat production rising at a steady clip: according to the Worldwatch Institute meat production has tripled globally since 1970.

Currently, around 25 percent of the world’s usable land is employed for pasture for our 1.7 billion heads of livestock, according to a report in 2010 entitled Livestock in a Changing Landscape. Moreover, 30 percent of arable land is used to grow food specifically to feed livestock with. This has had a massive impact on the world’s ecosystems, for example the majority of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest has been for cattle production. Around 5 percent of the world’s carbon emissions and 30 percent of methane emissions are also linked to livestock production.

Trend in trophic levels 1961-2009. Graph courtesy of: Bonhommeau et al.

Citation:

- Bonhommeau et al. Eating up the world’s food web and the human trophic level (2013) PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1305827110

Related articles

Foodies eat lab-grown burger that could change the world

(08/06/2013) Yesterday at a press event in London, two food writers took a bite into the world’s most unusual hamburger. Grown meticulously from cow stem cells, the hamburger patty represents the dream (or pipedream) of many animal rights activists and environmentalists. The burger was developed by Physiologist Mark Post of Maastricht University and funded by Google co-founder Sergey Brin in an effort to create real meat without the corresponding environmental toll.

African grass could substantially cut greenhouse gas emissions from livestock industry

(09/17/2013) Scientists will call for a major push this week to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture through the use of a modified tropical grass. Brachiaria grasses have been found to inhibit the release of nitrous oxide, which has a more powerful warming effect than carbon dioxide or methane, leading them to be called a super grass.

Eat insects to mitigate deforestation and climate change

(05/14/2013) A new 200-page-report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) urges human society to utilize an often-ignored, protein-rich, and ubiquitous food source: insects. While many in the industrialized west might turn up their noses at the idea of eating insects, already around 2 billion people worldwide eat over 1,900 species of insect, according to the FAO. Expanding insect-eating, the authors argue, may be one way to combat rising food needs, environmental degradation, and climate change.

Meat consumption jumps 20 percent in last decade with super-sized environmental impacts

(10/11/2011) Meat consumption and production remains on the rise, according to a new report Worldwatch Institute, with large-scale environmental impacts especially linked to the spread of factory farming. According to the report, global meat production has tripled since 1970, and jumped by 20 percent since 2000 with consumption rising significantly faster than global population.